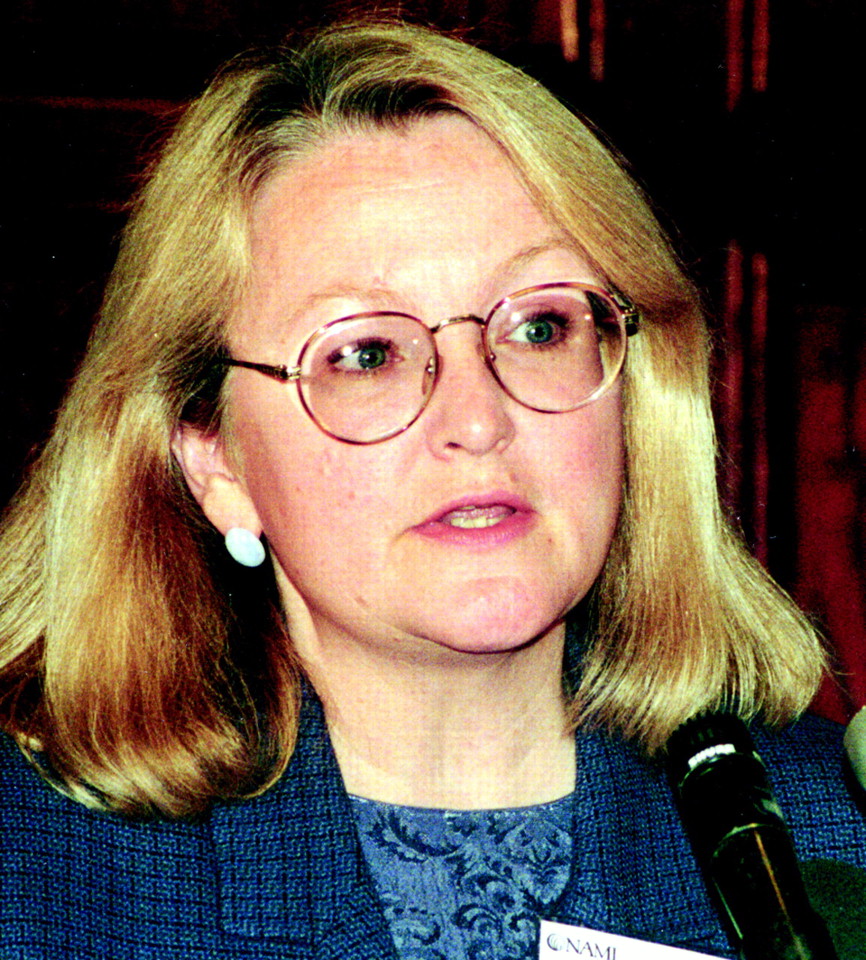

Laurie Flynn Leaves NAMI After 16 Years at Helm

Laurie Flynn: “Parity was a message as much as a change in policy.”

In 1984 NAMI was a relatively unknown network of grass-roots citizen advocates working to ensure that people with severe mental illnesses got the best care available and were treated with respect by a health care system that often ignored their needs. Most came to NAMI because they had a relative with a serious psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and were tired of seeing their loved ones dismissed or stigmatized.

At that time, however, NAMI had limited influence and access to the corridors of power. That changed under Flynn’s tenure. Headquartered in Arlington, Va., the organization now has more than 210,000 members, 1,200 affiliates, and a staff of 60. Flynn has become a familiar—and influential—presence in Congress, government meetings, and other forums where mental illness issues are on the agenda.

Flynn came to NAMI because of her background and interest “in bringing families and consumers into the policymaking process,” she said in an interview with Psychiatric News last month. It was after she assumed her NAMI post that one of her daughters was diagnosed with schizophrenia, an event that opened her eyes even further to the torment and struggles that the families of seriously mentally ill individuals endure, she said.

In her years as NAMI’s executive director, noted APA Medical Director Steven Mirin, M.D., “Laurie Flynn has been a major force in the fight to protect patients’ rights and enhance their access to quality care. With the help of her leadership, NAMI has grown in size, stature, and effectiveness.”

Jacqueline L. Shannon, president of NAMI’s Board of Directors, described Flynn’s departure as “a sad occasion for the organization.” Flynn, she noted, “played a vital part in the growth of NAMI and was there since its infancy. She has a real feel for what’s going on in the nation and led the way on many issues, particularly in the public policy arena, where she is well known by the nation’s leaders.”

Flynn told Psychiatric News that several accomplishments stand out from her tenure at NAMI’s helm. In particular, she cited the organization’s concentrated focus on boosting the science and research of mental illness, particularly as they impact treatments for and understanding of the most serious mental illnesses.

She is proud, she said, that a primary consequence of this focus on science and research has been a reduction in the stigma attached to mental illness and the people who have these disorders. “We have confronted stigma at every turn,” and as a result, Flynn said, “people have become more comfortable dealing with mental illness.”

She noted as well that she is proud of NAMI’s “aggressive championing of parity” for mental illness care at the federal and state levels. “Parity was a message as much as a change in policy,” she emphasized. Wherever some degree of parity was implemented, it told people that “mental illnesses are brain disorders and need to be covered just like all other such disorders, such as epilepsy and Alzheimer’s disease.”

Flynn noted that parity is one of the issues where the agendas of NAMI and APA diverged. NAMI has devoted its efforts to advocating for parity for the most severe mental illnesses, while APA believes that a much broader range of disorders need to be covered by any parity laws.

Other areas in which she noted that she steered NAMI on a course different from APA’s were NAMI’s push to reintegrate the National Institute of Mental Health into the National Institutes of Health a decade ago, its much stricter view of the circumstances under which psychiatric researchers should be able to use human subjects, and its advocacy for tighter restrictions on and more frequent monitoring of seclusion and restraint.

One area on NAMI’s agenda in which Flynn is disappointed about the lack of progress is the housing arena. Policymakers and health officials have failed to “deal substantively with the housing crisis confronting the mentally ill and their families,” she pointed out. “If we don’t deal with the lack of affordable housing along with associated treatment programs, we’ll never solve the homelessness problem. This is the single greatest problem our members tell us about.”

Advocates for the mentally ill compete with those for other disabled individuals for scarce dollars and attention, she noted, and stigma still leaves the mentally ill the last to have their needs addressed.

Flynn admitted to experiencing mixed emotions about leaving NAMI after 16 years. “It’s tough—I never really understood separation anxiety before. I have pride in my accomplishments, but lots of unfinished business,” she said.

Flynn told Psychiatric News that her departure was in part prompted by philosophical differences between her and the NAMI board over the organization’s future direction. “I’m 110 percent committed to advocacy and the critical role of the national office,” she said. But she pointed out that NAMI is “more than the national office.” It has 1,200 affiliates, many of which are calling for a shift in focus away from national advocacy and toward developing and strengthening local programs.

Shannon, the NAMI board chair, agreed with Flynn’s assessment, noting that the board wanted to see considerable strengthening of the state organizations, while Flynn believed that a stronger central office would be a more effective way for NAMI to achieve its goals.

Shannon declined to comment on reports that the NAMI board lost confidence in Flynn’s leadership and asked her to resign. Flynn stated that the agreement for her to leave NAMI “was a mutual decision” between her and the board.

Much of the criticism of Flynn and stories of disagreements between her and the NAMI board, Shannon told Psychiatric News, “come from organizations of former psychiatric patients who have long been vocal critics” of NAMI and its policies. Groups such as Citizens for Responsible Care and Research and the Support Coalition International contend that under Flynn’s tenure NAMI became too reliant on income from pharmaceutical companies. The groups believe that Flynn deserved to be criticized for her unwillingness to agree with them that drug treatment for mental illness is a form of forced treatment and oppresses rather than benefits people with mental illness. Shannon pointed out, however, that most of the pharmaceutical company money NAMI received has been in the form of “unrestricted educational grants that went to the NAMI Anti-Stigma Foundation. We have been very careful to keep these funds separate” from the rest of the NAMI budget, she said.

Next on Flynn’s professional agenda will be joining Columbia University’s psychiatry department, where she said she will help put together a major multidisciplinary effort on behalf of children and adolescents with mental illness. One of the project’s goals, she noted, will be to “educate and empower families who still feel very blamed and shamed and panic stricken when mental illness hits their family. We hope to be able to develop programs to prevent disability and chronicity” among young people who are mentally ill. ▪