Electronic Treatment for Depression Shows Promise

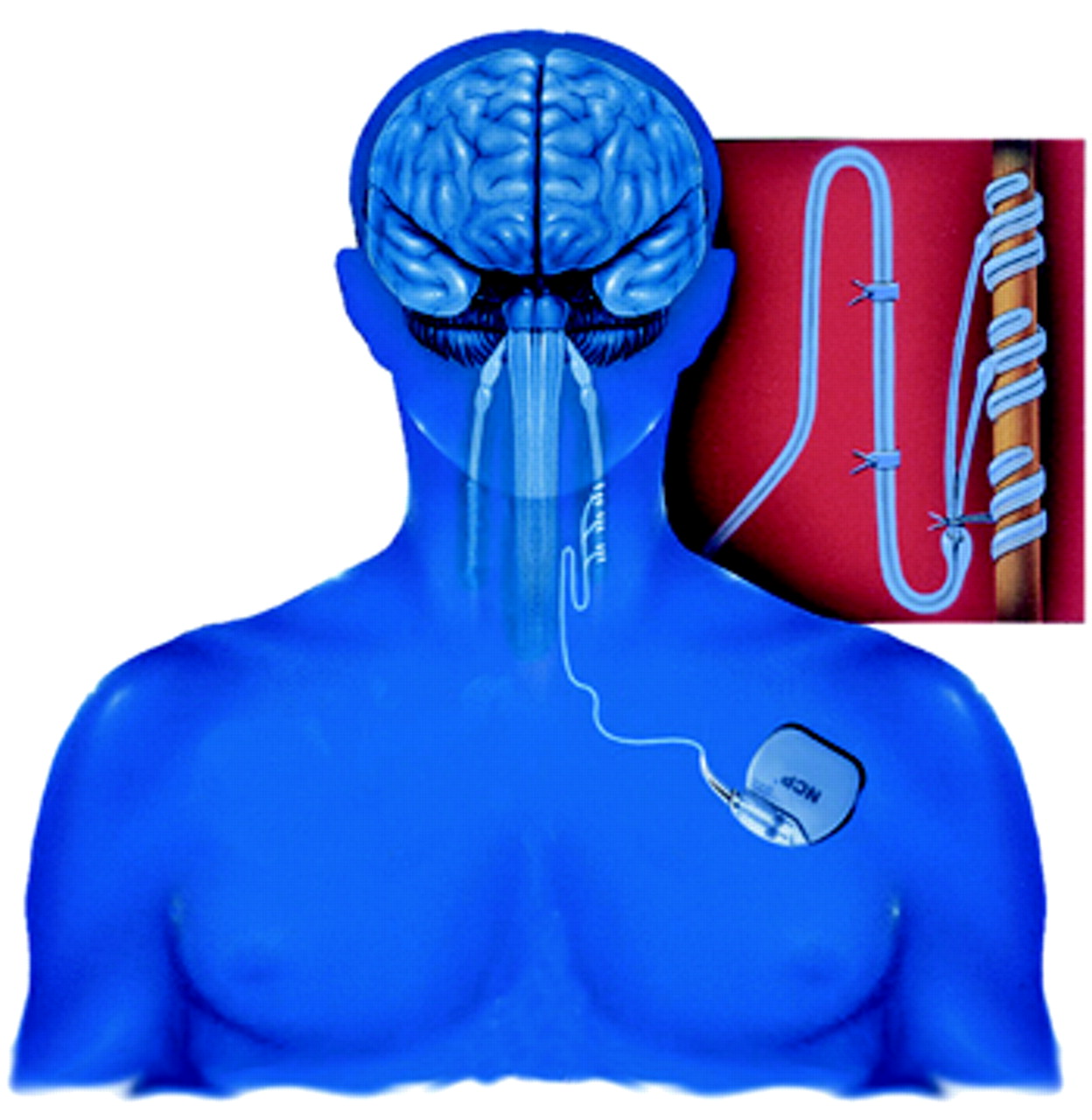

This is a graphic depiction of the NCP System, which has been approved in Canada and the European Union to treat resistant depression. It may also be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the same use.

This scenario is not science fiction. In fact, it is no longer just a “take” from a medical research setting, but a clinical reality since the technique has been approved for use in both Canada and the European Union.

The approval was announced at the Seventh World Congress of Biological Psychiatry, held in Berlin, Germany, in July. The announcement came from A. John Rush, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and one of the four psychiatrists who have been testing the technique.

It all started in 1987 when Houston-based Cyberonics was founded to design, develop, and market a unique device for the treatment of epilepsy and possibly other debilitating disorders. It was called a NeuroCybernetic Prosthesis (NCP) System.

The NCP System is an implantable medical device similar to a cardiac pacemaker. During a 30- to 90-minute surgical procedure, usually done on an outpatient basis, a stopwatch-sized generator is placed outside the chest cavity under the left arm, and a nerve-stimulation electrode is attached to the left vagus nerve in the neck.

Once the system is in place, a physician can then use an external programmer to turn it on, sending electrical impulses to the vagus nerve. The programmer can also be used to modify the electrical impulses in frequency, intensity, or duration or to turn the impulses off altogether.

The NCP System was first implanted in an epilepsy patient in 1988. It subsequently proved so successful at countering epileptic seizures that in 1997 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved it for use as an adjunct therapy for reducing the frequency of seizures in adults and adolescents who are over age 12 and had medically refractory seizures. The system was also approved for such use in Canada, the European Union, Australia, and a number of other countries.

To date, some 12,000 epilepsy patients in 24 countries have had experience with the system. It appears to be essentially safe, although patients have reported negative side effects such as voice alteration, shortness of breath, neck discomfort, and coughing.

A positive side effect, interestingly, has been reported as well—improved mood and cognition. This serendipitous discovery made Cyberonics executives wonder whether the system might also be used to counter depression. So they decided to approach a psychiatrist-medical scientist who they thought would be able to give them an educated opinion and who might be able to conduct a clinical trial to test the system. This was Mark George, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, neurology, and radiology at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston and director of the university’s Center for Advanced Imaging Research and of its Brain Stimulation Laboratory. George thought the idea had merit, and he agreed to conduct a trial for them.

George then recruited Harold Sackheim, Ph.D., of the New York State Psychiatric Institute to help him with the trial, and Sackheim in turn recruited Rush, and all three then brought a Baylor College of Medicine psychiatrist on board as well; she was Lauren Marangell, M.D. The “four horses,” as Rush described them to Psychiatric News, got the trial under way in 1998.

The phase-one trial, which was an open, pilot one, initially included 30 patients who suffered from serious, treatment-resistant depression and who had not been helped by therapies such as antidepressants or even electroconvulsive therapy. A NCP System was implanted into each of the patients, followed by a two-week recovery period with no electrical stimulation of the device. The system in each patient was then electrically stimulated for a 10-week period. Each patient was assessed for depression before, during, and after electrical stimulation.

By the end of 1999, it appeared that the system was indeed capable of exerting an antidepressant effect, at least in certain treatment-resistant patients. Forty percent of the 30 patients studied experienced a lessening of depression following stimulation with the system, the investigators reported in the December 1999 online edition of Biological Psychiatry (Psychiatric News, January 21, 2000).

After that, the trial was expanded to include 30 more patients, and all 60 of the patients were followed for two years.

Some 30 percent of the 60 patients experienced a substantial lessening of their depression after stimulation; half of this 30 percent had their depression lift altogether, Rush reported at the Berlin congress.

It was on the basis of these results, Rush told Psychiatric News, that the NPS System has been approved as a depression treatment in Canada and the European Union.

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial to test the technique in persons with treatment-resistant depression in the U.S. is now under way. George, Sackheim, Rush, and Marangell designed it in consultation with Cyberonics and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. All subjects in this trial will get the implanted device, but only half will get electrical stimulation turned on in the beginning; the other half will get stimulation turned on 12 weeks later. Rush described this as a “delayed treatment control.” The idea is to see whether the individuals who do not get stimulation during the first few weeks will do as well as or more poorly than those persons who get stimulation from the start.

If this trial produces positive results, Rush said that he believes that the FDA will approve the system for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression.

And if the method were to receive FDA approval for treating persons with treatment-resistant depression, what would that mean for American psychiatrists and their patients? “It would be the first new physical treatment with substantial efficacy since we discovered electroconvulsive therapy in 1938,” George replied. “So it would be revolutionary.”

But how about costs? The device and implantation of it currently run about $15,000. Subsequent visits to a psychiatrist to switch on electrical stimulation of the device or otherwise modulate it would, of course, cost extra. But current treatments for treatment-resistant depression aren’t cheap, either. Or as George pointed out: “I treat lots of people with treatment-resistant depression. It is a very costly illness. Patients tend to need frequent doctor visits and are often on very costly polypharmacy. They also require intermittent hospitalization. . . . A short course of ECT. . .can easily run around $15,000 or $20,000. So you can see that if the device were effective, it would make a lot of sense for an HMO or managed care company to pay for it because it would actually save money in the long run.”

As far as NCP System treatment for refractory epilepsy goes, most major American health insurance companies and Medicare pay for it, George added. ▪