Ethnic Variations in Depression, Suicide Rates Puzzle Researchers

Are certain American ethnic groups more susceptible to major depression than others? The answer is yes, according to a study conducted by Maria Oquendo, M.D., a psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and her colleagues and reported in the October American Journal of Psychiatry.

Oquendo and her colleagues gathered data about the depression status of various American ethnic groups from two surveys that had been conducted during the 1980s, the Epidemiological Catchment Area Study, conducted by the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Epidemiologic Survey (HHNES), conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. The investigators used the one-year prevalence rates of major depression for African Americans, whites, and Hispanics in Los Angeles from the ECA study, which was conducted in five sites in the United States. The investigators used one-year major depression rates for Puerto Ricans on the mainland United States, Mexican Americans, and Cuban Americans gathered by the HHNES in geographic areas where these Hispanic groups were most concentrated.

The one-year prevalence rates for major depression, Oquendo and her team found, were 2.5 percent for Cuban Americans, 2.8 percent for Mexican Americans, 3.5 percent for African Americans, 3.6 percent for whites, and 6.9 percent for Puerto Ricans living on the mainland United States.

When Psychiatric News asked Oquendo whether these results, which are based on 1980s data, apply to the present, she replied: “That is a very difficult judgment. Obviously they are dated information. . . . So I am not sure we can extrapolate directly about what’s happening today.” However, if the findings are still relevant today, one can conclude that Cuban Americans and Mexican Americans have a modestly lower prevalence of major depression than whites and African Americans, yet the prevalence of major depression among Puerto Ricans living on the mainland United States is about double that for whites and African Americans.

The reasons for these similarities and differences are not so apparent from the study. One possible explanation, the researchers suggest in their study report, is that “since the rates of major depression in Puerto Rico have been shown to be the same as in the general U.S. population, perhaps the migratory process selectively involves Puerto Ricans with higher levels of psychological distress.”

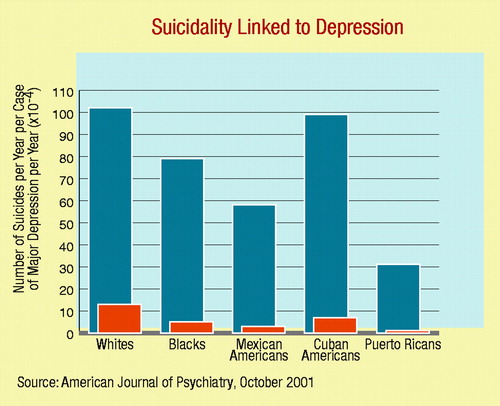

Even more baffling is why the prevalence of major depression among the various ethnic groups was not always found to coincide with the prevalence of suicide among the same groups, since major depression is well known to be a significant contributor to suicide.

Five ethnic groups studied by researchers at the New York State Psychiatric Institute had notable differences in their rates of suicide relative to one-year prevalence of major depression.

When Psychiatric News asked Oquendo why depressed Mexican Americans and depressed Puerto Ricans on the mainland appear to be especially buffered against suicide, she replied: “It may have to do with cultural issues such as relationship with the family and the extended support network, but also with the concept of fatalism. This concept is prevalent in these two cultures. The concept is that things will not necessarily go smoothly—you kind of expect that adversity will occur, and you have to tolerate it and deal with it. I think religion may be related to that as well. But these are just speculations on my part because we didn’t have data to analyze that.”

However, such data may be forthcoming, she indicated, since “we are currently doing a study looking at reasons for living among the Hispanics compared with non-Hispanics to see whether we can identify the particular things, at least cognitively, that might keep Hispanic people further from suicide, or protect them, if you will.”

Identifying psychological factors that protect people against suicide is a major goal of their research, Oquendo indicated.

“Ethnic and Sex Differences in Suicide Rates Relative to Major Depression in the United States” is posted on the Web at ajp.psychiatryonline.org under the October issue. ▪