Psychotherapy Changing Lives of Elderly Patients

The maxim goes “you can’t teach old dogs new tricks,” but it doesn’t say anything about older patients—or does it?

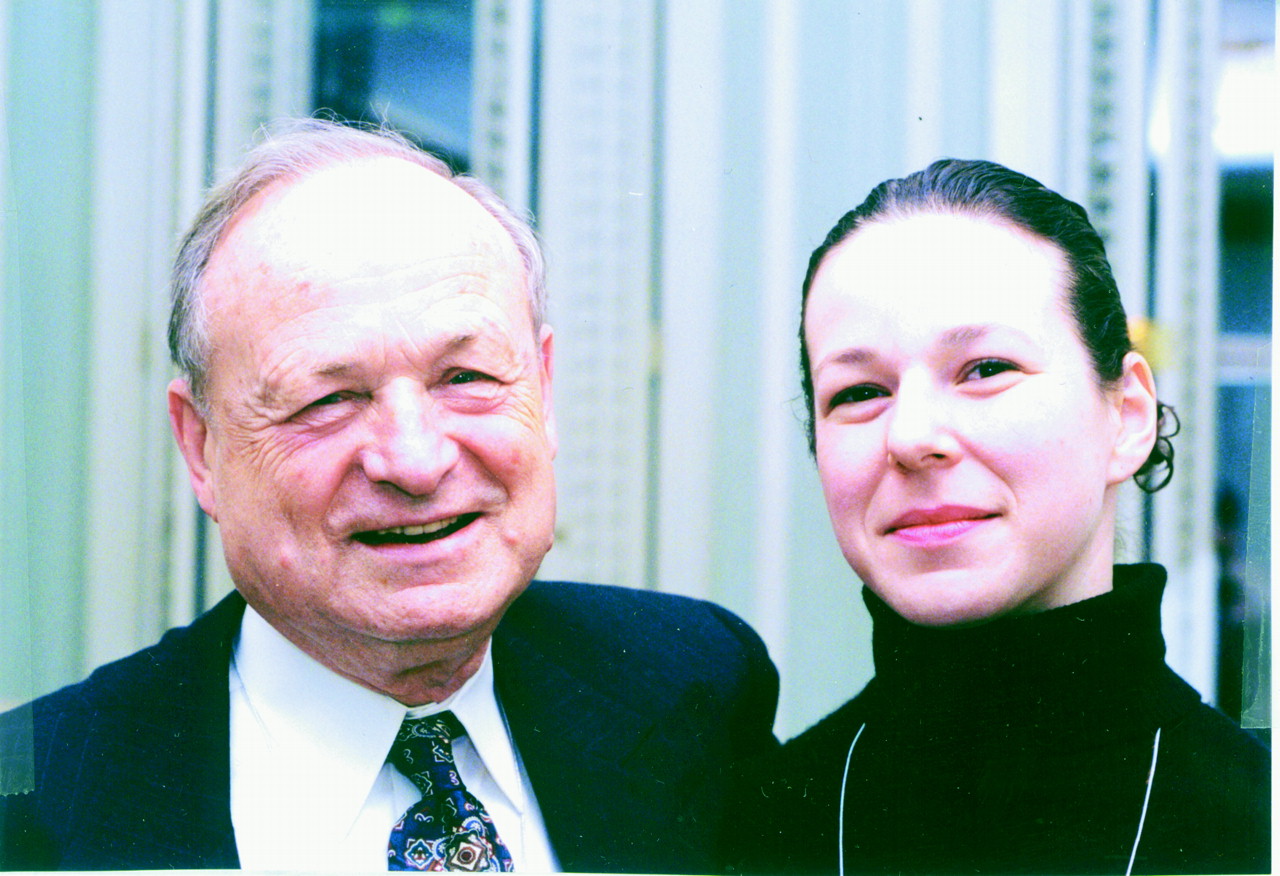

Psychiatrists Jerome Grunes, M.D., and daughter Dorothy Grunes, M.D., both of whom conduct psychotherapy with older patients, discussed this topic at the American Psychoanalytic Association’s December meeting.

A man died at age 92. Speaking at his funeral, his children pointed out that while he had been a despicable person until a decade before, after that he had started treating his wife and them more magnanimously. Was it a case of a Scrooge being awakened to his failings by ghosts? The man’s children did not say.

But Grunes, who was attending the man’s funeral, knew the reason, and it had nothing to do with ghosts. Twelve years earlier, the man had started psychotherapy with Grunes, and he had continued it until his death. In short, it was because of this lengthy psychotherapy that “he had changed,” Grunes explained.

Even when psychotherapy does not transform the minds, hearts, and behaviors of older persons, it can still benefit them in less dramatic ways, therapists attending the session reported.

For instance, it can sometimes help patients who have been estranged from their children become reunited with them. It can lead to better self-understanding in some cases. This attestation came from Betram Cohler, Ph.D., who is a therapist affiliated with the University of Chicago and has worked with both children and older persons. What’s more, achieving self-understanding in one’s later years has particular value today, Cohler believes, since people are living longer than they used to.

Psychotherapy can help some older folks feel more understood by others. This is the contention of a German gerontologist who attended the session. After all, she said, a major goal of psychotherapy with persons of any age is to give them the impression that they are being understood. Grunes expressed a similar opinion: One of the great things about psychotherapy is that patients feel that someone understands them, and such a feeling is of particular value to older patients.

Psychotherapy also seems capable of benefiting some older persons who are in the process of succumbing to Alzheimer’s disease. This testimony came from both Cohler and Grunes. When Grunes conducts psychodynamic therapy with such an individual, for example, he takes a history, just as he would with any patient, starting with the patient’s earliest memories and continuing up to the present. This storytelling, he explained, helps the pre-Alzheimer’s patient regain, at least for a while, a sense of coherence about his or her life.

Even when therapists give older patients their best, of course, not all profit from it. This reality too emerged from the American Psychoanalytic Association session.

One of the biggest psychological challenges of growing old, it seems, is having one’s body fall apart. Loss of mobility can be even more devastating than loss of sight or hearing. And while a psychiatrist who works with nursing home patients reported that she has been successful at helping some adjust psychologically to their physical decline, she has not been able to help others, she said. Dorothy Grunes, M.D., the daughter of Jerome Grunes and a psychiatrist herself, made a similar point. Elderly persons who break a hip rarely live more than six months afterward, she said. She suspects that it is not just because of the physical trauma that results from a hip break, but also because of the psychological trauma that ensues from losing mobility.

What’s more, when older persons both decline physically and carry some heavy psychological baggage, they may be especially resistant to help. Edwin Wood, M.D., a Houston, psychiatrist, told about a patient in his mid-70s who not only was going downhill physically but who also had experienced a bitter divorce, had a drinking problem, was alienated from his children, and had sexually abused his daughter when she was young. Although Wood put him on antidepressants and saw him twice a week for psychotherapy, the medication and psychotherapy did not seem to help much. The man became more and more depressed. Finally, the man’s girlfriend indicated that she did not wish to see him anymore. That seemed to be the final blow for him psychologically. He shot himself in the head in the bathroom. “He was simply bent on doing this,” Wood believes.

Not surprisingly, it can take a lot out of therapists when they fail to help older patients. Regarding the above patient, Wood admitted, “I felt betrayed; I was working so hard.” And when older patients whom a therapist likes die, that can be painful as well, Grunes conceded. Regarding the 92-year-old man he had treated for 12 years, he said, “I was very fond of him. He taught me a lot.” It was for that reason that Grunes attended his funeral.

Working with older patients has other rewards, too, those attending the session pointed out. “One of the greatest pleasures in working with older patients is seeing the variety of lives people have,” Grunes said, and if a therapist likes history, then listening to older folks recount their lives is sometimes even more pleasurable than reading history books.

And doing therapy with older people has its humorous moments, too, Grunes added. For instance, he has noticed that whereas the content of what pre-Alzheimer’s patients try to remember may elude them, the affect rarely does. As a result, one of his pre-Alzheimer’s patients ran into a man on the street whom he had known, and whereas he could not recall the man’s name, he did recall that he despised the man. So he cried out: “There’s that sonofabitch!” ▪