PET Scans Point Way to Better Alzheimer’s Diagnosis

Finding an accurate, reliable tool to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in its early stages has long been an elusive goal in medicine. A new study, in the November 7 Journal of the American Medical Association, provides strong evidence that physicians may now have that tool. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans, the authors reported, are highly sensitive at picking up changes characteristic of dementia and also have good specificity at teasing out the cause of the dementia.

Finding an accurate, reliable tool to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease in its early stages has long been an elusive goal in medicine. A new study, in the November 7 Journal of the American Medical Association, provides strong evidence that physicians may now have that tool. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans, the authors reported, are highly sensitive at picking up changes characteristic of dementia and also have good specificity at teasing out the cause of the dementia.

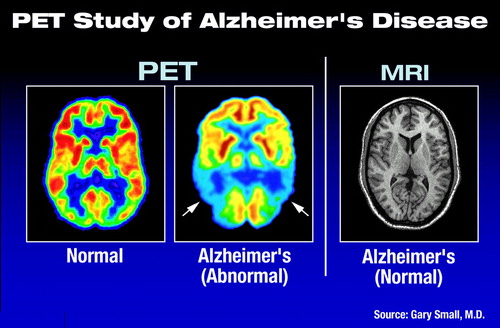

“For nearly 20 years,” said Daniel Silverman, M.D., Ph.D., head of the neuronuclear imaging group at the University of California at Los Angeles and an assistant professor in UCLA’s department of molecular and medical pharmacology, “we have had data that indicated that patients with Alzheimer’s disease would show some abnormality on PET scans, even when their MRIs were normal. But most of the data suffered from having been from very small studies—the largest previous cohort was 22 patients.”

Gary Small, M.D.: With PET scans, “we now have a proven, very sensitive diagnostic tool.”

“We looked for any place we could find that had any patients with both PET and autopsy data,” Silverman told Psychiatric News. The researchers ended up with PET data from 146 patients undergoing evaluation for dementia with at least two years of clinical follow-up at UCLA from 1991 to 2000 and 138 patients undergoing evaluation at international sites that included postmortem analysis of brain tissue. The 284-patient cohort is the largest source of PET-scan data correlated with clinical data and/or postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease to date.

“What this allowed us to do was, for the first time, to compile statistically significant data on just how accurate PET is compared with the gold standard of seeing the actual brain tissue [to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease],” Silverman said.

The group found that PET detected unspecified progressive dementia in 191 of 206 patients who were eventually diagnosed with some form of dementia (a sensitivity of 93 percent) and was able to pinpoint dementia of the Alzheimer’s type in 59 of the 78 patients in the study who had a final diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease (a specificity of 76 percent).

“We now have a proven, very sensitive diagnostic tool,” Small told Psychiatric News. Small said that the findings could lead to more accurate diagnosis at earlier stages of the disease and allow clinicians to institute appropriate treatments earlier.

“The main treatment right now is to use a cholinesterase inhibitor,” Small explained. “And there are emerging data that these drugs are effective, not just for Alzheimer’s disease, but also for things like vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia. So, where the PET is not quite so specific as it is sensitive, with the current drug regimens that doesn’t matter. Whatever the cause of the dementia, the drugs are likely to help.”

Both Silverman and Small noted that numerous studies have indicated that it is increasingly important to diagnose patients with dementia as early as possible. Several studies have indicated that cholinesterase therapy can significantly slow and potentially even arrest the progression of dementia, delaying the point at which a dementia patient must be put into a skilled nursing facility by as long as 18 to 26 months. Other studies have indicated that some drug therapies can also significantly reduce the time demands of caregivers, prior to the patient entering a facility.

“By the time patients finally come to a physician and says that they are having problems with their memory or language abilities, they already have significant declinations of brain function on PET,” said Silverman. Patients should undergo a thorough examination to rule out other causes of memory or speech problems, but if that work-up does not reveal anything, patients should be screened for dementia using PET.

“This could direct patients to the most appropriate management at the earliest possible stages of their disease,” he told Psychiatric News. “What isn’t clear is whether you can change the actual rate of neurodegeneration, but what you can clearly change is the rate of cognitive degeneration.”

Small is working hard for increased awareness and acceptance of PET as an accurate and appropriate diagnostic tool. He will participate in a Medicare hearing on coverage of PET for dementia screening in January.

“There are lots of economic arguments, and the cost analysis becomes complicated,” Small said, noting that the cost of brain PET scans can be quite variable but averages around $1,000 to $1,500. But the overall cost-benefit analysis is conclusive in that earlier initiation of appropriate treatment delays placement of patients into skilled nursing facilities. Although the medications used to treat patients with dementia are expensive, Small said, even the cost of a PET scan and a year of cholinesterase therapy together are easily eclipsed by one month in a nursing home.

“No one should be left hanging, with the physician saying, ‘Let’s see what happens in six months or a year’,” explained Silverman. “That is what is commonly done now, and the only thing that accomplishes is the delay of appropriate treatment by six months or a year.”

An abstract of “Positron Emission Tomography in Evaluation of Dementia” is posted on the Web at http://jama.ama-assn.org/issues/v286n17/abs/joc10908.html. ▪