CBT Beneficial in Treating Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

So report British researchers in the December American Journal of Psychiatry. They are Alicia Deale, Ph.D., a lecturer/cognitive-behavior therapist with the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College in London; Simon Wessely, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the Institute; and other colleagues.

Deale and her coworkers conducted a trial with 53 patients with chronic fatigue syndrome to determine whether CBT could help such patients over the long term. Twenty-eight of the subjects received 13 sessions of relaxation therapy, and the remaining 25 got 13 sessions of CBT. Relaxation therapy consisted of engaging in progressive muscle relaxation and rapid relaxation techniques. CBT consisted of planned activity and rest, a sleep routine, graded increases in activity, and a cognitive restructuring of counterproductive beliefs. For instance, subjects worked on thinking of symptoms as “hurting, not harming”—for example, not to equate muscle pain with muscle damage. They worked on eliminating counterproductive thoughts such as “If I can’t do something as well as I used to, it’s not worth doing,” “I have to do as much as I can whenever I’ve got the energy,” and “I’ll never get better.”

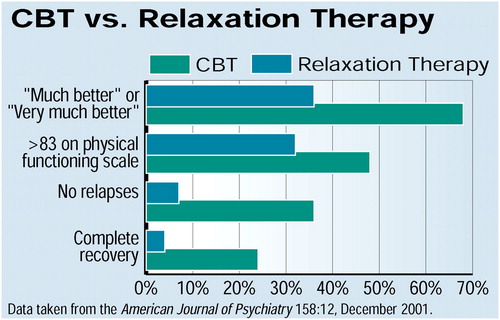

Five years later, Deale and her team had the 53 subjects rate themselves on how they were doing from a physical health and energy vantage point. For example, they rated themselves on global improvement, a seven-point scale from “very much better” to “very much worse.” They answered the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form General Health Survey, a 20-item scale of physical functioning that measures limitations caused by ill health. Scores on this survey ranged from zero (limited in all physical activities) to 100 (able to carry out vigorous activities). A score of 83 would indicate that a subject was doing well physically and could conduct moderate activities such as transporting purchases or moving furniture. They answered a Fatigue Questionnaire; 11 fatigue symptoms were rated, and a score of 4 or higher indicated excessive fatigue. They were likewise asked how many relapses they had experienced since treatment had ended. For employment status, they were asked if they were currently employed and, if so, the numbers of hours they worked per week.

The researchers then compared the results of how subjects from the relaxation-therapy group were doing from a physical health and energy standpoint with the results of how subjects from the CBT group were doing from this standpoint (see chart). Taking all the results into consideration, and especially whether the differences between the two groups were statistically significant, the researchers concluded that, whereas CBT was no cure-all for chronic fatigue syndrome, it could nonetheless produce lasting benefits for a number of persons with the syndrome.

The researchers then compared the results of how subjects from the relaxation-therapy group were doing from a physical health and energy standpoint with the results of how subjects from the CBT group were doing from this standpoint (see chart). Taking all the results into consideration, and especially whether the differences between the two groups were statistically significant, the researchers concluded that, whereas CBT was no cure-all for chronic fatigue syndrome, it could nonetheless produce lasting benefits for a number of persons with the syndrome.

Michael Antoni, Ph.D., a professor of psychology, psychiatry, and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami, is familiar with the research area pursued by Deale and her colleagues, and Psychiatric News asked him for his opinion.

“This study represents the first work to provide empirical evidence for the efficacy of a psychosocial intervention in effecting recovery, decreasing relapse, and diminishing fatigue-related symptoms in a chronic fatigue syndrome population over a five-year period. Whereas prior studies have indicated that such treatment gains may be possible over a period typically spanning six months, the present study is unique in offering evidence that such treatment gains may be durable over several years. . . .

“It was also significant,” Antoni continued, “that fully 88 percent of the CBT patients were still actively practicing their CBT skills at the five-year follow-up. The investigators were thus successful in getting patients to make real lifestyle changes and perhaps integrating CBT into their daily routine—the ultimate goal of disease management and stress management programs offered for a wide range of medical patients.”

Antoni also speculated on how CBT may be able to counter chronic fatigue syndrome from a physiological perspective: “Patients may become more aware of their internal resources, for example, energy levels, as well as external demands, for example, stressors, in such a way that they can more efficiently and preemptively negotiate the intersection between the two.” ▪