Suit Asks Court to Remedy Foster Care MH Crisis

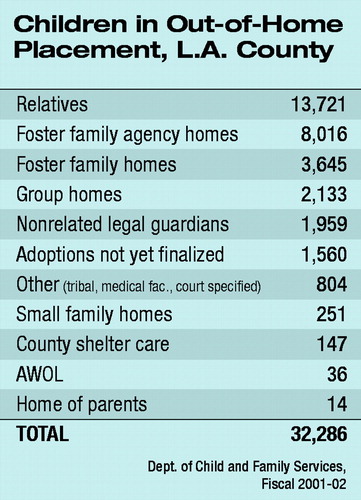

The Los Angeles County child welfare system is not providing appropriate mental health services to about 50,000 children under its supervision, including 32,000 children in foster care.

That allegation was made by six legal advocacy groups who filed a lawsuit in July in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California. They are the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law; Center for Law in the Public Interest; American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of Southern California; Youth Law Center; Western Center on Law and Poverty, Protection and Advocacy Inc.; and the law firm Heller Ehrman, White, and McAuliffe.

“We want the Los Angeles Department of Child and Family Services [DCFS] to change from a crisis-driven system that puts children in available slots to a well-planned system that provides community-based mental health services, behavioral support, and case management to children under its supervision,” Ira Burnim, legal director of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, told Psychiatric News.

Nearly all foster children in Los Angeles are eligible for Medicaid and meet the requirements for the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program, which includes mental health, according to the complaint.

Children are removed from their homes and placed in foster care mainly due to neglect and abuse. Between 60 percent and 85 percent of foster children nationwide have significant mental health problems, said Burnim.

‘Too Little and Too Late’

Yet “foster-care children are rarely assessed for psychiatric conditions, and treatment, if provided, is often too little and late,” said Burnim.

For example, plaintiff Mary B was removed from her home when she was 13 due to sexual and emotional abuse and neglect. She is legally blind. She did not receive therapy until three years and 28 placements later, although social workers knew about her history of abuse, the suit points out.

Mary B’s placements included four foster care homes, 16 psychiatric hospitalizations in which her underlying trauma history was not addressed, and three emergency shelter stays, alleges the complaint. Another plaintiff spent 10 years in foster care and experienced 36 placements.

Mary B’s placements included four foster care homes, 16 psychiatric hospitalizations in which her underlying trauma history was not addressed, and three emergency shelter stays, alleges the complaint. Another plaintiff spent 10 years in foster care and experienced 36 placements.

“Too many children with behavioral and emotional problems are bounced between foster care and group homes. When those placements inevitably fail because of worsening mental conditions, children are deemed unplaceable and sent to psychiatric institutions and emergency shelters,” said Burnim.

The plaintiffs want to ensure that foster children are placed in “family-like” settings rather than institutions.

“Warehousing troubled children at MacLaren Center, the county’s emergency shelter, often for months and without mental health services is an obscenity. Housing large numbers of troubled children together also increases the risk of their being revictimized,” said Burnim.

System Retraumatizes

Marilyn Benoit, M.D.: “When children lose their foster home placement, it reinforces their negative perception of themselves and disrupts their ability to form trusting relationships.”

She initiated a partnership between AACAP and the Child Welfare League of America last March to improve the design, delivery, and outcomes of mental health and substance abuse services provided to foster care children and their families.

“When children are removed from their homes, they often are traumatized and face separation issues. They express their distress in behaviors that often get them punished and eventually removed from the home,” said Benoit. “When children are ejected from their foster home placement, it compounds their trauma, reinforces their negative perception of themselves, and disrupts their ability to form trusting relationships,” Benoit added.

The Los Angeles County DCFS declined to comment to Psychiatric News about the pending lawsuit.

Marvin Southard, D.S.W., director of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (DMH), told Psychiatric News that much of the information in the complaint was outdated. “We began making reforms four years ago.”

About 40 percent of the Los Angeles County EPSDT budget is devoted to providing mental health services to foster children. The amount has tripled in the last four years to $90 million, said Southard.

DMH is implementing a DCFS assessment project based on a similar one that was implemented in the juvenile-justice system. DCFS mental health professionals have begun screening children entering the foster-care system to determine whether they need a comprehensive psychiatric assessment, said Southard. “Eventually we plan to screen the 32,000 children already in the foster-care system.”

DCFS mental health professionals will provide treatment initially to foster children who need it. Children needing long-term services will be referred to local community mental health clinics, said Southard.

DMH also has initiated a “wraparound” service program for about 100 foster children who have serious mental illnesses and have had multiple placements. “We plan to expand the program in the next year to serve an additional 300 children,” said Southard.

He plans to include more children at risk of being removed from their homes in the wraparound program in the future. “The goal is to help children maintain long-term placements and relationships with families, whether biological or adoptive,” said Southard.

As more children are assessed and treated when they are removed from their homes, Southard expects that fewer will need to be placed in the 20 group homes that provide expensive day-treatment programs.

It costs DMH about $5,000 a day per group home to pay for a psychiatrist and team of mental health professionals to be on staff and treat seriously mentally ill children, said Southard.

He estimated that about 5,000 of the 32,000 foster care children are seriously mentally ill or emotionally disturbed. Hundreds of seriously mentally ill children are also placed in high-level group homes in other counties, group homes that contract with community mental health providers for services, locked community residential treatment facilities, the state psychiatric hospital, and, as a last resort, the MacLaren Center, said Southard.

Burnim said that the plaintiffs have proposed meeting with the defendants to negotiate a settlement agreement. “We should know soon whether they are willing to do that.”

A press release describing the lawsuit and a statement by Burnim are posted on the Web site of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law at www.bazelon.org/newsroom/7-18-02lacase.htm. ▪