Data Raise Concerns About Polypharmacy Trend

Psychiatrists will say there are a number of reasons why they combine antipsychotic medications, whether the combination is two atypical antipsychotic medications or one atypical with a conventional antipsychotic. Yet among those reasons is probably not something like “It’s backed up by the evidence base” or “It’s recommended in the practice guidelines.”

A workshop last month at APA’s 2003 annual meeting in San Francisco on antipsychotic polypharmacy versus monotherapy in patients with schizophrenia attempted to explore two important questions: Why do physicians prescribe multiple antipsychotics? And when a patient is on combination therapy, does the patient generally improve?

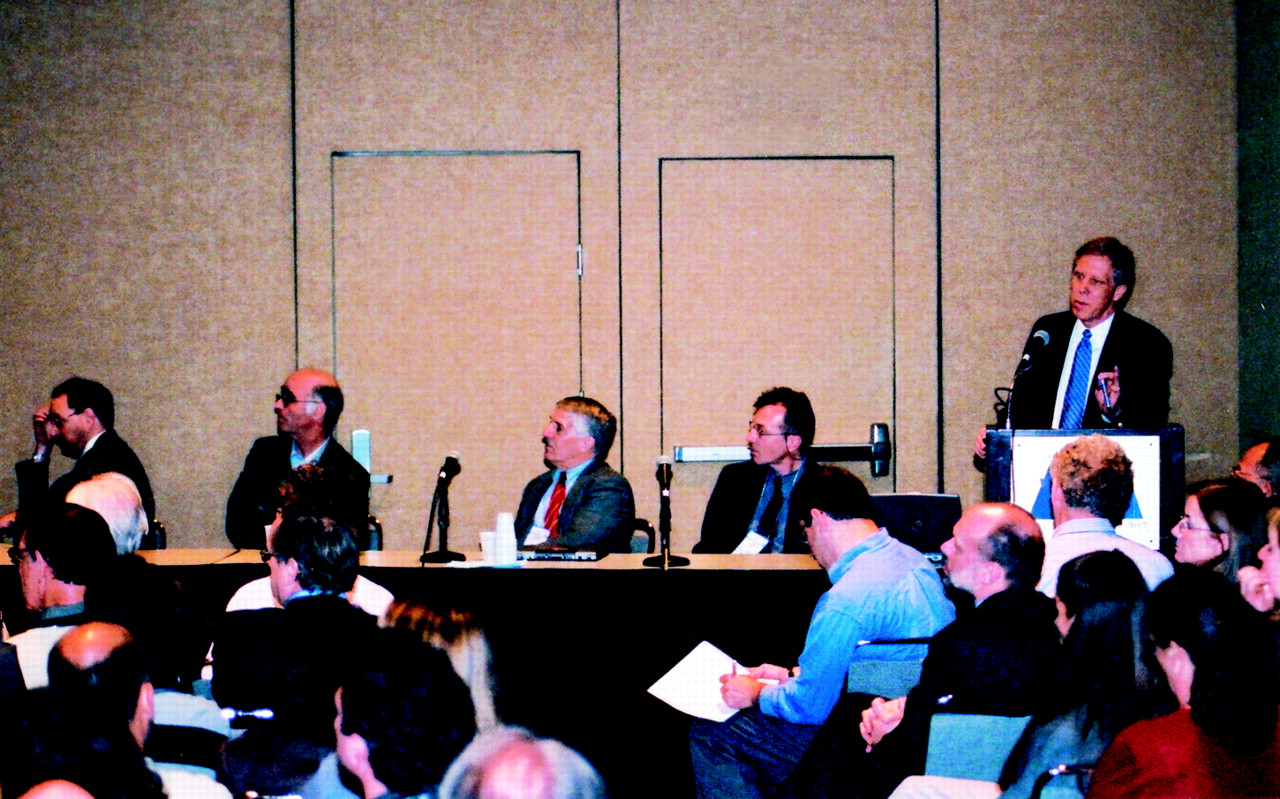

“Studying whether or not combinations are better than a single drug is a very difficult question to tackle,” says Donald Goff, M.D. (at podium). He is joined by panelists (from left) Andre Tapp, M.D., Alexander Miller, M.D., Robert Rosenheck, M.D., and William Honer, M.D.

Not Uncommon, But Right Course?

Prescribing multiple medications to a patient with a severe medical disorder is not, after all, that unusual. In other medical specialties, in fact, it is not only common, but widely accepted and integrated within best-practice treatment guidelines. Cardiologists, for example, often use multiple medication “cocktails” to bring hypertension under control, while pulmonologists do likewise for obstructive pulmonary disease and oncologists for various types of cancer.

Why then would the use of multiple medications to treat a patient with a severely debilitating medical disorder, such as schizophrenia, be such a hot topic of debate? Everyone is looking for evidence to back up the practice.

“In psychiatric practice,” Tapp said, “we hear about many psychiatrists who use combination antipsychotic therapy, and we want to understand why physicians do that. How common is the practice of polypharmacy, and do patients actually improve with multiple medications? We really don’t know the answers yet.”

Tapp was joined at the workshop by Alexander Miller, M.D., director of the schizophrenia module of the Texas Medication Algorithm Project at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in San Antonio; Donald Goff, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Harvard University and Massachusetts General Hospital; Robert Rosenheck, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Yale Medical School and director of the Veterans Affairs Northeast Evaluation Center; and William Honer, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia.

More Questions Than Answers

Both Tapp and Rosenheck have explored the question of why clinicians prescribe more than one antipsychotic medication to a patient. And while the two seem to agree on some points, their data may in a way pose more questions than they answer.

In a survey of 1,794 patients in the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound system, Tapp looked at the patients who were prescribed at least one antipsychotic medication. Of those, Tapp found 93 patients (5.2 percent) who were on combination therapy for longer than 30 days. The vast majority of the combinations involved the addition of a conventional antipsychotic to an atypical medication the patient was already taking.

“We then asked physicians what was their intention—what were they trying to achieve with the combination therapy?,” Tapp said.

The majority of physicians (74 percent) responded that the conventional antipsychotic was added to try to achieve better control over the patients’ positive symptoms. The remainder said the combination was prescribed in response to failure of the previous treatment.

The survey results were published in the January issue of Psychiatric Services. In a second study, which has been submitted for publication, Tapp looked at subjects’ Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores before and after the patients were prescribed a second drug to determine whether they obtained any clinical benefit from the combination.

“Eight weeks after adding the second drug,” Tapp said, “the patients’ positive core symptoms and negative core symptoms were not statistically any different, but the patients’ general psychopathology did improve.”

In this study at least, the clinicians’ rationale for polypharmacy was not borne out by the PANSS scores, Tapp said.

Rosenheck looked at a sample of more than 78,000 veterans who had been diagnosed within the VA system at least twice as having schizophrenia and also looked for evidence of polypharmacy.

“Across 125 VA medical centers across the country,” Rosenheck said, “there was broad variability: Anywhere from 1.5 percent all the way to 40 percent of patients who were taking at least one antipsychotic were prescribed polypharmacy.”

Rosenheck looked for any patterns or trends that would predict which patients would receive more than one antipsychotic. He found that older patients, as well as patients who were African American, had a comorbid substance abuse disorder, or had comorbid major depression were less likely to receive more than one antipsychotic, while those who had greater than a 60 percent disability or had been hospitalized in the last year were more likely to be prescribed more than one antipsychotic. Also, patients at research hospitals were more likely to receive combination therapy.

“And this is all a familiar pattern to me,” Rosenheck said, “because if you look at something like adherence to dosing schedule guidelines, you see general indicators that the sicker patients not only get higher doses, they get multiple medications.”

Rosenheck, who tracked administrative prescription data from 1999 to 2001, noted that the rate of antipsychotic polypharmacy is increasing over time. “This may well reflect the greater use of the atypicals in an atypical/conventional pattern—about 80 percent of the polypharmacy in the VA system is an atypical plus a conventional.”

Rosenheck also asked physicians who prescribed more than one antipsychotic what benefits polypharmacy provided. Nearly 85 percent said that the patients were refractory to monotherapy, and 58 percent thought that the patient “needed a little conventional [antipsychotic medication] to get better control of positive symptoms.”

Often, said Goff, when a patient is not doing well on a particular drug, the physician prescribes a second drug while tapering off the first drug. But six weeks later or so, when the physician asks the patient which drug worked better, the patient often says that he or she felt best on the combination during the switch.

Unfortunately, there are few hard data to back up clinicians’ and patients’ perceptions that combination antipsychotic therapy works better. Only a handful of open-label trials and one small placebo-controlled trial have actually looked at whether combination therapy has real benefits. And, Goff cautioned, while there are numerous case reports of benefits from combinations of antipsychotics, most patients who are written up as case reports do not represent the majority; in fact, they are atypical.

Tapp concluded that before prescribing a second antipsychotic to a patient, the physician should take a hard look at the drug the patient is already taking.

“Is the patient on an optimum dose of the drug,” Tapp said, “or is the patient failing because the dose is too low?”

Rosenheck added that it is also “important to remember that if a patient is not doing well on a certain medication, you need to look not only at the medication, but also at adding psychosocial interventions.” ▪