New Studies Raise Questions About Antipsychotic Efficacy

Whether a patient is enduring the ravages of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or psychotic depression, the questions are paramount and the same for each: Of the six newer antipsychotic medications-often referred to as atypical (or second-generation) antipsychotics -on the market in the United States, which is most likely to give the patient the greatest benefit? And are these six medications really better than the older "conventional" (or first-generation) medications, as many seem to believe?

Whether a patient is enduring the ravages of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or psychotic depression, the questions are paramount and the same for each: Of the six newer antipsychotic medications-often referred to as atypical (or second-generation) antipsychotics -on the market in the United States, which is most likely to give the patient the greatest benefit? And are these six medications really better than the older "conventional" (or first-generation) medications, as many seem to believe?

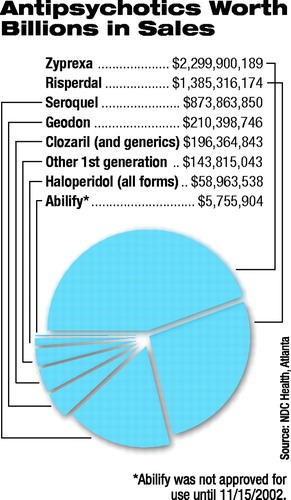

The elusive answers to these deceptively simple questions could impact millions of lives-15 million prescriptions were written for the top two antipsychotic medications alone in 2002, and 80 percent of all antipsychotic prescriptions were written for second-generation medications, according to NDC Health, an independent Atlanta firm that tracks prescription sales.

Many now believe that a growing body of research, including a new report that appeared in the June Archives of General Psychiatry, provides a significant step forward in nailing down those answers. John M. Davis, M.D., the Gillman Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), and Ira Glick, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University, along with Nancy Chen, M.S., a graduate research data analyst in the department of psychiatry at UIC, determined that there are indeed answers: The newer medications are better than the older medications, and not all of the newer medications were created equal: Some may have better efficacy and fewer side effects than others.

Other experts disagree, some almost vehemently -but not necessarily with the research methodology or the actual quantitative statistical analyses. It is the interpretation of the Davis/Glick analysis that is being hotly debated internationally, spawned when the new study's results were first publicly presented in full at a symposium at APA's annual meeting in May. Clinical Debate Heats Up "The only issue of extreme clinical significance for patients with schizophrenia is, How do you get patients back up to as close to their baseline as possible?" said Glick, who chaired the symposium at APA's annual meeting. Of note, the symposium was not an industry-supported program, and no industry funding was used for any of the studies presented at the symposium.

Glick estimates that most patients get "about half of the way back" to their baseline with the help of medications. The key is finding the right one.

"The message I give is that there's been a huge shift away from first-generation medications, at least in the U.S., in favor of second-generation medications, and the reason, I think, is not so much the efficacy issue, but because of fewer extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS)-the side-effect profiles look so much better," said Glick. Because of that, he said, "patients take the drugs more, they relapse less, they are hospitalized less, and the overall cost to the system is significantly less."

Glick quickly added that many may disagree with his statement.

Joining him on the panel were Davis; John Geddes, M.D., senior clinical research fellow in psychiatry at the University of Oxford and a member of the United Kingdom National Schizophrenia Guideline Development Group; and Stefan Leucht, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Munich, Germany, and a visiting fellow at the Zucker Hillside Hospital in New York. Both Geddes and Leucht also recently published studies comparing the efficacy and sideeffect profiles of antipsychotic medications. Joining the group as a discussant was Stephen Marder, M.D., professor in residence and chief of psychiatry at the University of California at Los Angeles and the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Marketing Hype vs. Clinical Benefits The answers to the questions surrounding antipsychotic medications are highly subjective, depending not only on how the questions are framed but also by whom.

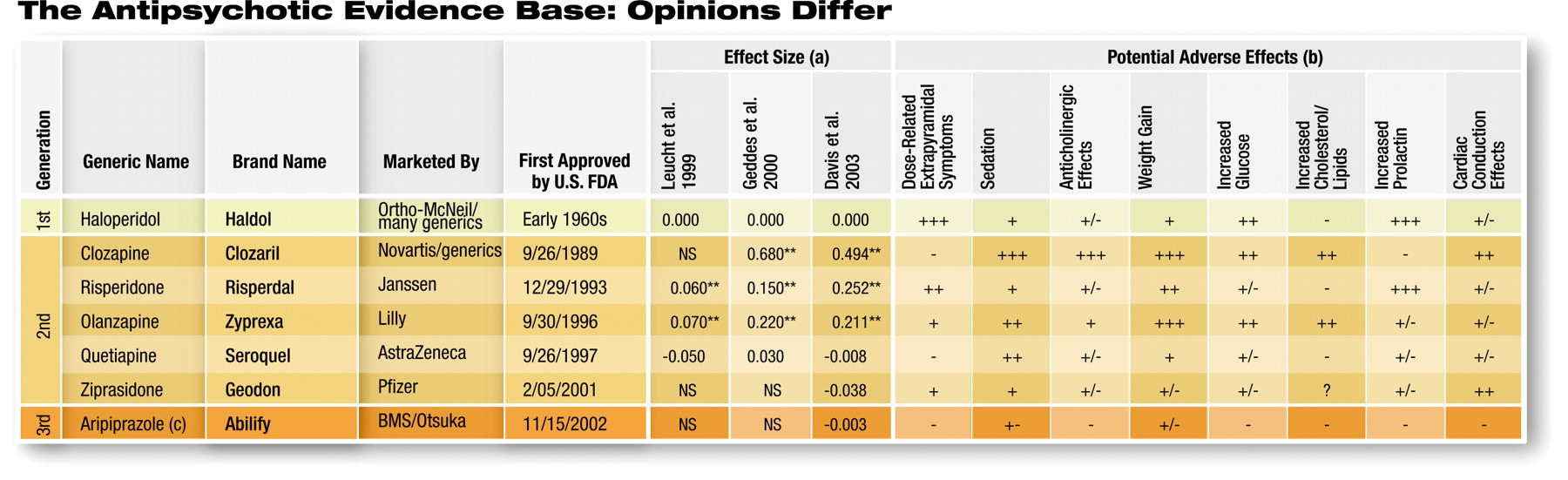

The companies that manufacture and market the six medications-clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole (listed in the order in which they were approved by the U. S. Food and Drug Administration)-have a vested interest in the answers. And rightfully so, many would agree-especially their stockholders. After all, sales of antipsychotic medications in the United States in 2002 totaled $6.3 billion, according to IMS Health, an independent international firm that tracks prescription medication data worldwide. U.S. sales are projected to reach $7.6 billion by 2005. That places antipsychotic medications at number five in the top 10 therapeutic classes by total sales volume. As a result, companies aggressively market their individual medications to physicians throughout the world. Whether the companies reach them through advertising in medical publications (including this one), detail visits, or "educational" materials and events, all emphasize that their product "works better" than competitors' products or has a better side-effect profile -or both. These marketing claims are not without merit. Each company has reams of data to support its product claims.

Today the vast majority of research funding for psychotropic medications (as well as other classes of medications) originates with the pharmaceutical industry. While a study from one drug company supports the finding that its product is superior to those of its competitors, a study from another company indicates that its product is the best. How then does a clinician look to the evidence base and make an informed decision when that evidence base seems to be so conflicted? The Art of Meta-Analysis In the last several years researchers have turned to the meta-analysis-a "study of all the studies."

"The value in systemic reviews lies in the pooling of very large amounts of data that increase statistical power," Geddes said at the symposium. In short, instead of looking at one clinical trial with several hundred or a thousand patients taking a medication, pooling the data from many trials of the same drug on different patient groups permits researchers to study the effects of the medication across much broader populations.

"Meta-analysis allows you to weight an individual study by its size," Geddes said, with the effect being that a study with 2,000 patients has more statistical significance than a study of only 200.

Yet researchers familiar with meta-analysis and its methods noted several significant limitations.

"These studies are only as good as the data that go into them," Rajiv Tandon, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan, told Psychiatric News.

One of the largest limitations of meta-analysis, both Geddes and Davis noted, is that of publication bias. Researchers commonly limit a meta-analysis to the inclusion of peer-reviewed, published studies on a given medication, which most acknowledge runs the risk of discounting unpublished studies in which the data showed less or even no benefit from the medication being tested.

It is possible, Glick noted, that any result of a meta-analysis could be skewed by the fact that the vast majority of the data being analyzed were generated by the pharmaceutical industry, potentially introducing a conflict of interest that could bias the data. Glick said the concern is important, and he is in the process of separating the data that he and Davis used in their meta-analysis to determine whether the results differ if only nonindustry- funded studies are analyzed. He should have the result of that analysis by December and will present it that month at the annual meeting of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. At this point, though, he said, "anecdotally it doesn't look very different, and that gives me some hope" that the overall results are valid.

Each of the researchers Psychiatric News spoke to on the issue noted that the National Institute of Mental Health's Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) will provide the first independent data on comparative effectiveness of the drugs in question (Psychiatric News, May 18, 2001). However, the results are not expected for at least two years.

But Glick also observed that if almost all of the currently available data come from the pharmaceutical industry, it is reasonable to infer that the data, if indeed biased, are likely to be biased in the same direction -that is, favoring each manufacturer's medication. Effect-Size Nebula "The heterogeneity of all of these individual studies is a very significant problem, and [psychiatric researchers] are just beginning to touch on that," emphasized Tandon, who also attended the annual meeting seminar.

For example, Tandon told Psychiatric News that studies of patients with schizophrenia may use different assessment scales, each of which measures slightly different variables in different ways. Most clinical trials of medications for schizophrenia have used either the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Assessment data of patients taking medications may vary depending upon which scale was used, and the assessment scores derived from each scale are not interchangeable, though they may be roughly but not directly comparable (Original article: see box at bottom right).

Another potential problem inherent in a meta-analysis of antipsychotics occurs because the trials aren't identical: Some compare the newer antipsychotic medications with placebo, while others compare the drugs to an active comparator, most commonly haloperidol or chlorpromazine.

Another potential problem inherent in a meta-analysis of antipsychotics occurs because the trials aren't identical: Some compare the newer antipsychotic medications with placebo, while others compare the drugs to an active comparator, most commonly haloperidol or chlorpromazine.

In addition, most researchers would agree, sample size does matter. A clinical trial involving several thousand subjects has a higher level of significance than a smaller or less-rigorous study.

In the 1980s, in an effort to get around the difficulty of not being able to compare pooled data directly, the concept of an "effect size" was born. Medical statisticians developed effect size as a measure of the magnitude of a treatment effect compared across independent groups (see box on facing page).

Using effect size allows researchers to pool a large quantity of apparently disparate data while statistically controlling for the differences inherent to data collection and analysis methodologies. To Agree or Not Agree In 1999 the University of Munich's Leucht published the first multidrug metaanalysis of efficacy and extrapyramidal side effects of the newer antipsychotics, including olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole. Sertindole has since been pulled from the market due to concerns about adverse events (including death) involving cardiac rhythm disturbances.

Leucht's study, which was published in the January 4, 1999, Schizophrenia Research, analyzed 31 studies (2,300 patients), some of which compared the four medications with placebo and some of which compared them with haloperidol. While all of the medications were more effective than placebo, he determined that the average effect size was only 0.25.

Compared with the active comparator, haloperidol, however, olanzapine and risperidone were slightly superior to the first-generation drug, while quetiapine had no statistically different effect size (see table above). Leucht cautioned that his analysis included only one study with data on quetiapine. He noted, however, that the newer-generation medications were less likely to induce EPS.

Since 1999 Leucht has published several other studies-most recently in the May 10 issue of Lancet-comparing newer antipsychotics with the low-potency, firstgeneration drug chlorpromazine. In that study he determined that the newer medications were "moderately more efficacious" than optimum doses of chlorpromazine.

In 2000 Geddes published his metaanalysis, comparing amisulpride (not available in the U.S.), clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole with first-generation medications-generally haloperidol or chlorpromazine.

Geddes identified what he believed was a consistent trend, which has led to significant debate. He acknowledged that clozapine had a significantly higher effect size, relative to haloperidol (a point that none of the researchers debate), as did both risperidone and olanzapine. However, he doesn't believe the effect size differences for risperidone and olanzapine are real.

"When we separated the studies based upon the dose of haloperidol that the atypical antipsychotic was compared with, consistently when the dose was less than or equal to 12 mg of haloperidol a day, the atypical antipsychotics had no benefits in terms of efficacy or overall tolerability, although they did retain a modest advantage in terms of extrapyramidal side effects," Geddes said at the symposium. When a newer drug was compared with haloperidol at a dose in excess of 12 mg per day, there was a trend toward greater improvement in patients on the newer medication.

Geddes believes that the apparent improved efficacy of newer antipsychotics is an artifact, due at least in part to the increasing side effects of higher-than-recommended doses of haloperidol. Patients taking higher doses of the first-generation drug would appear to be not doing as well, simply because of the side-effect burden, he explained.

In their meta-analysis, Davis and Glick set out to address the dose-effect question. "We found very convincingly that [the increased efficacy of the newer antipsychotics] is not due to the dose of the haloperidol comparator," Glick told Psychiatric News.

The research, Davis told Psychiatric News, first focused on efficacy and found a statistically significant advantage in the efficacy of the atypicals over the standard drugs. "Everyone agrees on that," he continued. "It's just how they interpret that advantage that we argue about."

Davis and Glick included a dose-response analysis as part of their meta-analysis to try to answer the question directly.

"In our review of the dose-response studies on haloperidol, we showed that an extrahigh dose of haloperidol was no worse than a moderate dose," Davis said. "A high dose of haloperidol absolutely causes more side effects, but efficacy [in our studies] did not fall off."

The Davis and Glick analysis is the most extensive to date, encompassing 124 studies (18,272 patients) that compared firstgeneration antipsychotics with second-generation ones, and 18 studies (2,748 patients) of head-to-head comparisons between second- generation agents.

They concluded, once again, that clozapine had significantly better efficacy than haloperidol, and both risperidone and olanzapine had modestly better efficacy than haloperidol. Quetiapine was not significantly different from haloperidol, which was true of the two newest drugs on the market, ziprasidone and aripiprazole.

"That is an important issue here," Glick emphasized. "We are not saying that quetiapine, ziprasidone, and aripiprazole are not good drugs; we simply don't have enough data yet to get a really statistically significant finding."

Davis and Glick also conducted a subanalysis, using only the data included in Geddes's analysis, and came up with the same effect sizes as Geddes did.

"Even though we approached it from two different points of view," Davis noted, "we agreed on the raw data," almost a significant accomplishment in itself, he said. What's a Clinician to Do? "The absence of EPS really explains in a way why the atypicals are in fact better for negative symptoms, better for cognition, and in fact better for depression," said Tandon, whose review of the efficacy of antipsychotics appeared in a supplement to the January Psychoneuroendocrinology. "The patient does not have the dysphoria associated with akathisia or the cognitive difficulties driven by Parkinsonian symptoms. So this EPS advantage to the newer atypicals is a very real advantage."

Clinically, all of the researchers agreed, a key to maximizing efficacy-regardless of the specific antipsychotic medication used- is limiting EPS. Davis noted that "there is real disagreement, particularly between me and Dr. Geddes, but also between Dr. Geddes and Dr. Leucht. At least," Davis concluded, "our symposium got that out there, and [provided a forum] for some public debate. It was clearly the first time all of us have come together in one place at one time for a nonindustry-funded and unbiased discussion of a very important topic."

For Web links to the research studies cited in the above chart, access this story online at <http://pn.psychiatryonline.org>. ▪