Canada’s Single-Payer Plan Solves Some Access Issues

Researchers have come up with yet another approach to fund health care for the approximately 41 million Americans who lack health insurance.

In an article in the August 21 New England Journal of Medicine, lead author Steffie Woolhandler, M.D., reported that in 1999 health administration costs were $1,059 per capita in the United States, as compared with $307 per capita in Canada.

After excluding retail pharmacy sales and other categories for which administrative data were not available, administration costs accounted for 31 percent of health care expenditures in the United States and 16.7 percent of health care expenditures in Canada.

David Himmelstein, M.D., one of the authors, said, “We could save so much money [by switching to a Canadian-style system] that we could cover all of the uninsured with money left over for prescription drugs for seniors.”

Woolhandler and Himmelstein are co-founders of Physicians for a National Health Program (see story on Original article: page 21).

The study was conducted by researchers at Harvard Medical School and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. They analyzed the administrative costs of health insurers, employers’ health benefit programs, nursing homes, home care agencies, and physicians and other practitioners.

The authors argued that the difference in costs is due to the overhead attributable to private insurance companies in the United States and to the fact that doctors and hospitals must deal with hundreds of insurance plans, each with different coverage and payment rules. In Canada, physicians bill a single insurance plan using a simple form (see story on Original article: facing page).

Michael Myers, M.D., a former president of the Canadian Psychiatric Association who practices in Vancouver, said, “Billing is simple and takes very little staff time.”

He added that because reimbursement rates are transparent and psychiatric services are fully reimbursable, “psychiatrists are paid for every minute they are working.”

Psychiatrists need not concentrate on medication management to survive financially, because other types of psychiatric care are equivalently reimbursed, said Myers, who is also the chair of the Psychiatric News Editorial Advisory Board.

How do the two systems compare on other factors?

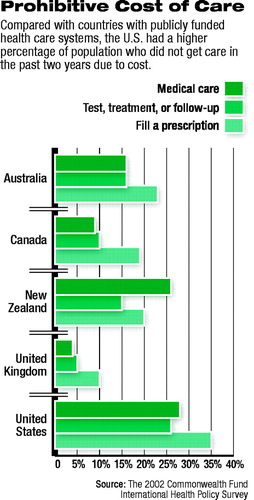

The Commonwealth Fund conducted a survey in 2002 consisting of interviews with adults with health problems in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The survey screened initial random samples of adults 18 or older to identify those who met at least one of four criteria: reported their health as fair or poor, or in the past two years had serious illness that required intensive medical care, major surgery, or hospitalization.

The Commonwealth Fund conducted a survey in 2002 consisting of interviews with adults with health problems in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The survey screened initial random samples of adults 18 or older to identify those who met at least one of four criteria: reported their health as fair or poor, or in the past two years had serious illness that required intensive medical care, major surgery, or hospitalization.

Canadians were less likely than residents of all other countries except the United Kingdom to report that they went without medical care because of cost, while Americans were most likely to report access problems due to cost. The respective figures are 28 percent in the U.S. and 9 percent in Canada.

Access problems due to cost in Canada most frequently concerned routine dental care and prescription drugs, which are not covered by the federal government.

Canadians, however, were most likely of all respondents to report difficulty in seeing a specialist and long waits. Fifty-three percent of Canadian respondents reported difficulties in seeing a specialist, and 24 percent reported long waits for appointments with doctors, compared with, respectively, 40 percent and 14 percent for Americans.

Myers agreed that a prospective patient might have to wait as long as three months to see a psychiatrist in Canada, unless the condition is an emergency. “There aren’t enough psychiatrists,” he said.

Regardless of supply problems, however, the quality of candidates for psychiatric training is high because, according to Myers, “The quality of life for psychiatrists here is good.”

The federal government controls the funding and number of residency slots for psychiatry, thus enabling it to limit supply.

Myers said that primary care doctors in Canada receive training in diagnosing depression and how to treat it with short-term cognitive and supportive therapies and medication.

Mental health services provided by psychologists and social workers are not reimbursable through the Canadian health plan. Myers said, “People are prepared to pay for the treatment.”

As in the United States, many Canadian psychiatrists believe that patients are discharged from psychiatric hospitals and units even though they could benefit from additional inpatient treatment.

Myers, who is on the staff of St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, said, “Physicians make the discharge decisions instead of the managed care companies, but we still feel pressure to empty beds because we need them for other patients.”

He added that Canada, like the United States, lacks an adequate system of psychosocial supports in the community for people with mental illness.

Canadians have identified targets for reform of their system. In November 2002, “Building on Values: The Future of Health Care in Canada,” a report of the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, was released.

The mandate of the commission, also known as the Romanow Commission, was to engage Canadians in a national dialogue on the future of health care and to make recommendations to preserve the long-term sustainability of Canada’s “universally accessible, publicly funded health care system.”

Commission members recommended establishing a federal cash-funding floor of 27 percent of the cost of insured health services, integrating priority home care services (including mental health case management), improving timely access to care, and providing federal funding for catastrophic drug coverage.

The report offered 47 detailed recommendations that included cost estimates and timeframes for implementation.

A summary of the Commonwealth Fund survey report, “The Canadian Health Care System: Views and Experiences of Adults With Health Problems,” is posted at www.cmwf.org/programs/international/canada52003_db_641.pdf. Information about the report of the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada is posted at www.hc-sc.gc.ca/english/care/romanow. ▪