Words, Photos Evoke Different Grief Reactions

In recent years, psychiatric scientists have become increasingly interested in the psychological process of grieving. They have found that as many as 40 percent of bereaved individuals suffer from major or minor depression; that bereaved persons are at high risk for suicide and an increased risk of death from other causes; and that antidepressant treatment can lead to a marked decrease in bereavement-related depression.

And now some psychiatric researchers have conducted a preliminary study to better understand the biology of grieving as well.

They have found that words pertinent to the death of loved ones provoke stronger grief responses than do photos of such persons, and the strongest response is elicited when such words accompany the photos. They have also found that specific brain areas are activated when grieving individuals view photos of dead loved ones or hear words relevant to their passing.

The study was conducted in the psychiatry department of the University of Arizona Medical School in Tucson. The lead investigator, Harald Guendel, M.D., is now affiliated with the Institute and Polyclinic for Psychosomatic Medicine, Psychotherapy, and Medical Psychology in Munich, Germany. Study results appeared in the November 2003 American Journal of Psychiatry.

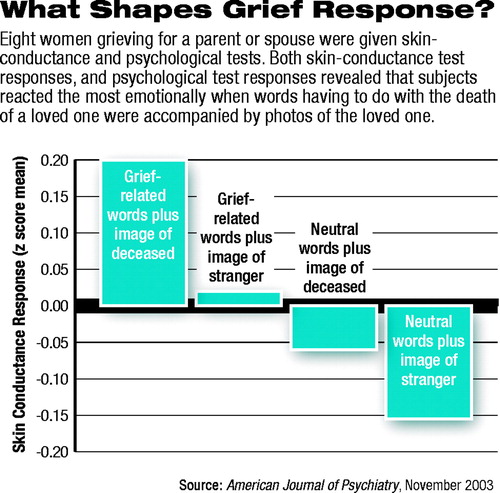

Eight women who had been grieving on average for eight-and-a-half months for a parent or spouse agreed to take part in the study. Each woman was shown a photo of her deceased loved one accompanied by neutral words; a photo of a stranger accompanied by words pertinent to the death of her loved one; a photo of her deceased loved one accompanied by words pertinent to the death of that loved one; and a photo of a stranger accompanied by neutral words.

During each of these four experimental conditions, the subjects were given a skin-conductance test to measure their psychophysiological reactions, and after each condition they were also asked to rate their psychological responses to what they had seen and heard. In addition, during each of the experimental conditions, the scientists used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to determine which of the subjects’ brain areas were activated.

Both the skin-conductance tests and the psychological-response ratings suggested that the subjects experienced their least-strong emotions when they saw a photo of a stranger accompanied by neutral words, and that they experienced their strongest emotions when they saw a photo of their loved one accompanied by words relevant to the death of their loved one (see chart).

Both the skin-conductance tests and the psychological-response ratings suggested that the subjects experienced their least-strong emotions when they saw a photo of a stranger accompanied by neutral words, and that they experienced their strongest emotions when they saw a photo of their loved one accompanied by words relevant to the death of their loved one (see chart).

The fMRI images revealed that different areas of their brains were activated when they heard words about the death of their loved one, viewed photos of their loved one, or both.

For example, the precuneus—an area of the inner surface of the cerebral hemisphere above and in front of the corpus collosum—was the brain area most robustly activated by words having to do with the death of a loved one. The precuneus is involved in the conscious recall of memory-related imagery. The fact that it was activated by words rather than photos may have been due to the words’ arousing visual images of the loved one’s dying.

In contrast, the posterior cingulate gyrus/cuneus was one of the brain regions most dramatically activated when subjects saw a photo of their loved one. The posterior cingulate is involved in the retrieval of autobiographical memories, episodic memories, and amnesia for personal events.

And the cerebellum was activated in subjects both in response to the photo and words having to do with the death of their loved one. Thus the cerebellum, which modulates affective, cognitive, autonomic, and motor functions, may also play an essential role in the coordination of emotional and cognitive functioning in the context of grief, the researchers believe.

In fact, activation of the cerebellum during grief elicitation surprised him, Guendel admitted to Psychiatric News. “Neuroscience is only just beginning to understand the role of this complex brain region,” he said.

Needless to say, this study needs to be repeated with a larger group of subjects to see whether the results hold up, Guendel and his team said in their study report. Yet such research is valuable, they contended, because identifying the neural correlates of grief may contribute to the elucidation of the physiological effects of bereavement on physical health. For instance, persons who lose a spouse through death are known to be at heightened risk of a fatal heart attack during subsequent months. How might grieving alter their brains to trigger this “broken heart” phenomenon?

The study was financed by the Arizona Department of Health Services and American Death Educators and Counselors.

The study, “Functional Neuroanatomy of Grief: An fMRI Study,” is posted online at http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/160/11/1946?. ▪

Am J Psychiatry 2003 160 1946