Lots of `Bad News' Dim MH Care Reform Prospects

Last July, after the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health issued its report calling for a “fundamental transformation” in the mental health system, then APA President Marcia Goin, M.D., pointed out the need for adequate funding to support any major structural change.

At APA's 2004 annual meeting last month, Michael Hogan, Ph.D., who was chair of the commission, offered an overview of the “Troubling Fiscal Dynamics of Mental Health Care.”

“It's almost all bad news,” he said. Hogan described four major problems that limit the pace of reform in mental health.

Mental Health Care out of Mainstream

First, Hogan said, is a “two-tiered system of care” that relegates treatment for serious mental illness to a separate system managed by the government that is “outside of the mainstream of health care.”

He told Psychiatric News that among the reasons for this separate system of care is that the country's de facto insurance system is employer based. Serious mental illness most frequently occurs when a person is at the age to lose coverage from parents and renders him or her unable to work and gain coverage independently.

In fact, Hogan told the audience, the employer-based insurance system is a“ much more fundamental” reason than lack of parity for the need for a public safety net for those with serious mental illness.

Although he believes that care offered by public psychiatric institutions can be “far superior” to that offered by the private sector, Hogan explained later to Psychiatric News that “in a market-oriented and tax-resistant economy, public care—irrespective of quality— is viewed as worse and thus perpetuates stigma.”

Funding Streams Fragmented

One source for this problem, Hogan argued, is that the country has successfully “implemented the reforms we were supposed to implement.”

In the 1970s, he said, the view of reform was that the country needed a network of community mental health centers with a wide array of services coordinated by case managers.

Many of the services needed, however, have not yet been funded through the federal government.

In 1980 a commission headed by former surgeon general Julius Richmond, M.D., issued the National Plan for the Chronically Mentally Ill with recommendations that ultimately led to funding for mental health services through Medicare and Medicaid and a “proliferation of responsibility in lots of federal agencies,” as the view broadened about the kinds of supportive services needed.

Congress changed Medicaid and Medicare and other programs, such as Social Security, providing more resources for mental health care, but also creating more fragmentation.

Federal fragmentation of funding streams translated into fragmentation at the state and community levels.

The result, said Hogan, is that people with serious mental illness and their family members often must navigate a complicated system on their own at a time when their emotional resources are severely taxed by illness.

Resources Decline

Erosion in funding for mental health services in both the private and public sectors further complicates reform efforts.

Hogan reminded the audience that when the Carter Commission issued its report in 1978, 12 percent of the money spent on health care went to mental health services. By 1997, the last year for which data are available, the figure had shrunk to 7 percent.

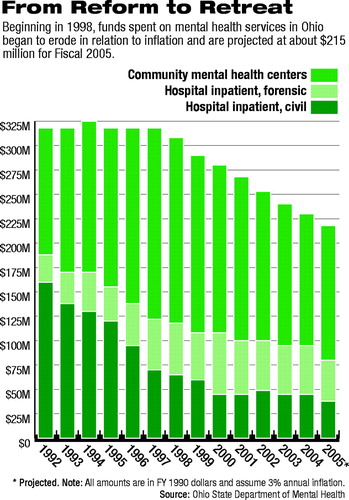

He offered examples of changes in funding patterns for mental health in Ohio, where he has directed the Department of Mental Health since 1991.

The state undertook a shift of resources from hospital to community care beginning in 1992. During that period, inflation-adjusted state general reserve funds (GRF) spent on mental health services remained almost constant at approximately $310 million, as measured in 1992 dollars.

The amount spent on community care, however, showed a steady increase, with relatively proportionate reductions in expenditures on inpatient care.

Beginning in 1998, GRF funds spent on mental health services began to erode in relation to inflation and are projected at about $215 million for Fiscal 2005 (see chart on page 19).

“This is not about budget cuts,” said Hogan. Mental health has fared “far better than most agencies in terms of budget cuts.” It reflects “long-term budget inattention,” which is “much scarier than budget cuts.”

Medicaid Is Double-Edged Sword

The final factor is what Hogan called the “Medicaidization” of mental health funding. “Medicaid might have both saved our bacon and burned it,” he said.

The program provides “essential resources” for community care, medications, and elements of inpatient care for people with mental illness and also funds general health care services for them.

But its eligibility standards are a “poor fit with need” for persons with mental illness, according to Hogan.

Medicaid's two major funding mechanisms, managed care and fee for service, have exhibited problems in implementation.

Some states have “success stories” in implementation of managed care, but most stories do not show success. Successful implementation of managed care through capitation requires sufficient funding at the outset. Otherwise, said Hogan, it becomes “decapitation.”

Ohio maintains a fee-for-service model that operates through county boards to CMHCs. With decreased GRF funding, those centers increasingly offer only services that Medicaid will reimburse and serve only Medicaid-eligible clients.

Resolving the Problem

Hogan concluded with observations and questions about the difficulty of resolving each of these problems.

He said that the problem of two-tiered care would require comprehensive health care reform and cannot be fixed within the mental health system alone.

Ameliorating the problem of fragmentation legislatively would require changes in Medicaid, Medicare, ERISA, and Social Security, “just for starters.”

“That is why the commission proposed transforming care,” said Hogan. “A big-bang theory of changing mental health focused just on the federal government is likely to fail.”

When times are tight, it is a “hugely complex” problem to stem or reverse the erosion of funding, he added.

Hogan then asked a final question, “Who do we see about Medicaid?”

He noted that the program's major funding role makes state Medicaid agencies at least as significant for mental health care as state mental health departments.

Hogan said that the commission had recommended a voluntary, collaborative approach to expanded state leadership for improving mental health care.

“The president's 2005 budget proposes a $44 million initiative to support expanded state mental health plans. Better coordination with Medicaid should be a key aspect of those plans,” he said.

“Troubling Fiscal Dynamics of Mental Health Care” was a presentation at the session “Wither the States?,” sponsored by the American Association of Community Psychiatrists and the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors and supported financially by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. ▪