State-Funded Health Plan Finds Jump in Antipsychotic Use in Youth

The proportion of children who became new users of antipsychotic medications doubled from 1996 to 2001 among those enrolled in TennCare, Tennessee's public health insurance program for Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured.

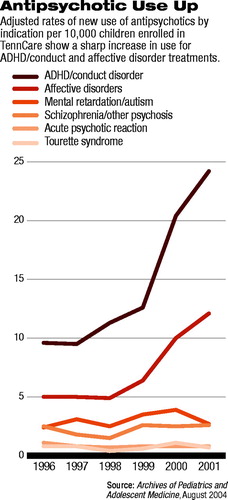

Increases in new antipsychotic use were particularly steep for conduct disorders and affective disorders, according to a report in the August Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine.

According to the study, the vast majority of the new users are receiving atypical antipsychotics. In 1996, 6.8 percent of new users received an atypical antipsychotic; by 2001 this had increased to 95.9 percent.

(New users were defined as those who were alive and continuously enrolled in TennCare for 365 days before and 90 days after the date of the first antipsychotic prescription. Children and adolescents had to be 2 to 18 years old and could not have used antipsychotics in the preceding 365 days.)

“Although this trend coincided with the introduction of the atypical antipsychotics, it is also possible that it was influenced by changing attitudes and practices regarding the use of pharmacotherapy for mental disorders in children,” wrote lead author William O. Cooper, M.D., M.P.H., an associate professor of pediatrics at Vanderbilt University.“ Data from studies of hospitalized children suggest that atypical antipsychotics can successfully control disruptive behavioral symptoms. On the other hand, before the introduction of the atypical antipsychotics, the severe and frequent adverse effects of antipsychotics led to the recommendation that these agents be used only in exceptional cases.

“A recent systematic review of the evidence supporting use of atypical antipsychotics in children and adolescents for [disruptive behaviors] concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support their efficacy,” Cooper added.

But child and adolescent psychiatrist David Fassler, M.D., said that while it is popular to disparage the use of antipsychotic medications in children, their increasing use does not necessarily mean that they are being prescribed inappropriately.

“We should not jump to the conclusion that an increase in the use of these medications automatically indicates a problem,” he told Psychiatric News. “We really need to understand more fully how the medications are being used and monitored.”

Fassler noted that specific recommendations about the use of antipsychotic medications for aggressive youth—based on clinical experience and published data—appeared in the February 2003 Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (see box on Original article: page 42). That article is not referenced in the report by Cooper and colleagues.

Fassler said the authors were right in pointing out that controlled studies of the use of antipsychotic medications in children are lacking. And he agreed with their cautions regarding the potential for inappropriate use and risk of significant side effects.

“But the issue is more complex,” he said. “The question is how the medications are being used, whether the kids are being evaluated and monitored, and what dosages are prescribed.

“If we limited our pharmacotherapy practice for children to treatments that had achieved the level of evidence-based practice, you would probably be limited to two or three interventions,” he said.

Cooper's retrospective cohort study examined medication records for children enrolled in Tennessee's TennCare program during the period from January 1, 1996, through December 31, 2001.

TennCare is the state's program for Medicaid enrollees and uninsured individuals. It operates under a 1994 federal waiver that permitted broadened eligibility to include persons of low to moderate income who were uninsured but would not qualify for Medicaid under federal guidelines.

The study analysis was restricted to the uninsured and those whose enrollment was through the largest Medicaid component of the program, Aid to Families With Dependent Children. This excluded children who might have been enrolled as a result of severe mental illness and who, therefore, were likely to have had antipsychotic use prior to enrollment.

Results adjusted for demographic characteristics showed that the proportion of TennCare children who were new users of antipsychotics nearly doubled during the study years, from 22.9 per 10,000 in 1996 to 45.4 per 10,000 in 2001.

Among the new users, 43.1 percent were diagnosed as having ADHD or conduct disorder; 14.2 percent, bipolar disorder; 8.7 percent, schizophrenia or other psychosis; 7.2 percent, another affective disorder; 6.2 percent, mental retardation; 4.5 percent, other psychiatric disorders (primarily adjustment reactions); and 2.2 percent, an acute psychotic reaction.

Only a small proportion of new users had diagnoses of Tourette syndrome (2.1 percent) or autism (0.2 percent).

The new users had substantial previous use of other psychotropic drugs, primarily stimulants (20.4 percent), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or other antidepressants (29.6 percent), and lithium or other mood stabilizers (13.7 percent).

In an editorial in the same issue, Peter Conrad, Ph.D., a professor of social sciences at Brandeis University, called on medicine to examine the larger social implications—both costs and benefits—of increasing use of psychotropics in children.

“From a social perspective, defining more and more children's behaviors as medical problems diverts our attention from the possible social and psychological origins of these difficulties,” he wrote. “In our medicalized culture, once an issue is defined as a medical problem, it becomes difficult to refocus on social or population-based solutions. More subtly, the treatment of behavioral and learning problems with psychotropics may reduce our appreciation and tolerance of difference.”

He added, “Physician researchers have often called for specific studies of the safety, adverse effects, and efficacy of these medications for pediatric populations. This is an important and urgent task, but it is also time to ask why there has been such an upsurge in the use of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents and to systematically investigate the medical and social origins and consequences of this phenomenon.”

An abstract of the study, “New Users of Antipsychotic Medications Among Children Enrolled in TennCare,” is posted online at<http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/158/8/753>.▪

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004 158 753