Film Documents Victories In One Schizophrenia Battle

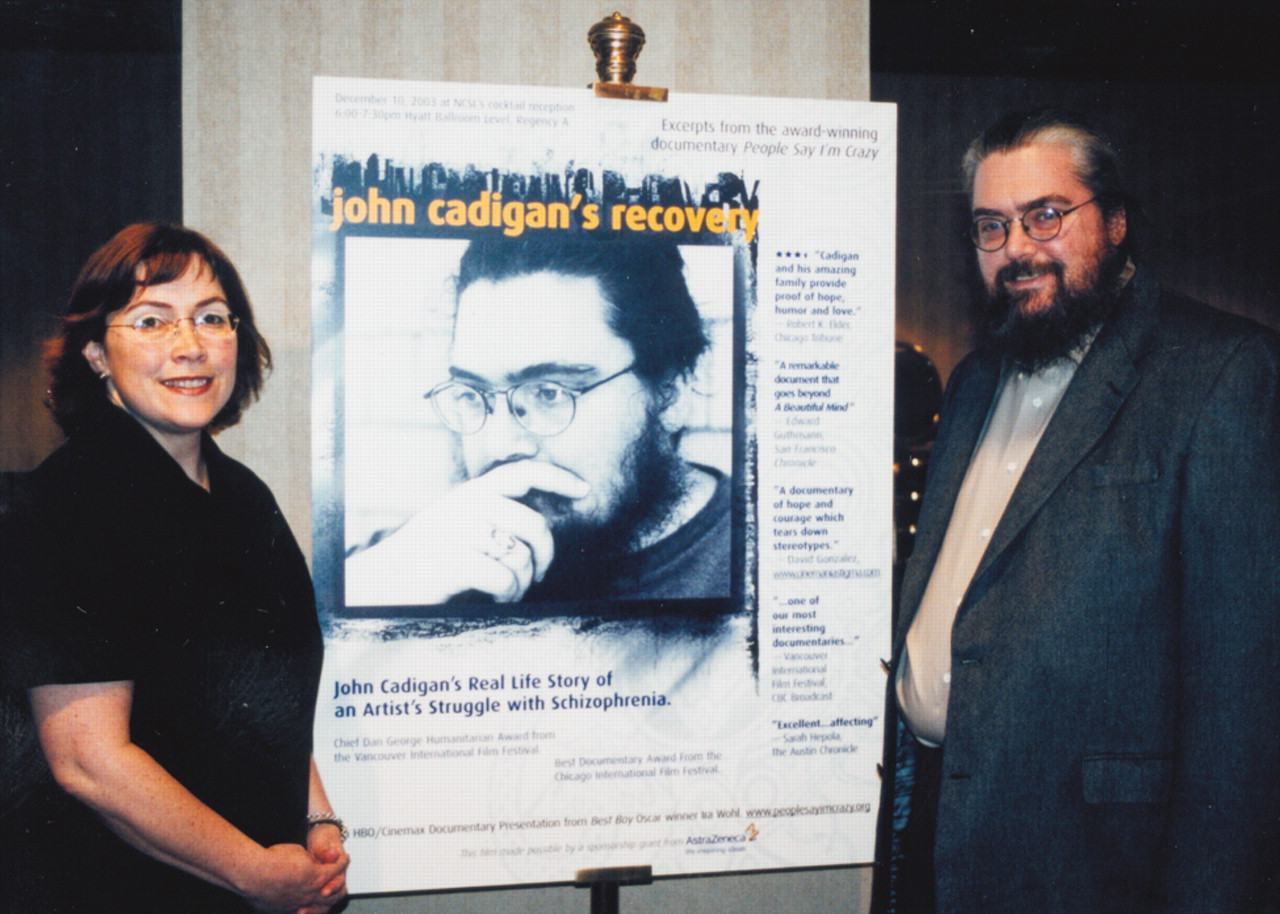

Katie Cadigan (left) and her brother, John, who is diagnosed with schizophrenia, came to Capitol Hill in December to promote their new film, “People Say I’m Crazy.”

His basement apartment in Pittsburgh became a prison of sorts. “I stopped going to classes because I was too afraid. . . . I would hardly ever leave,” he said.

His mind, however, became the ultimate prison. “I thought they were all out to get me—I thought they were bugging my telephone, following me, and taking pictures of me.”

Cadigan’s recollections of his first psychotic break in 1991 are immortalized in a documentary film, “People Say I’m Crazy,” which chronicles his more than decade-long struggle with schizophrenia.

Cadigan, 33, appeared with his sister, Katie, the film’s producer, at the forum of the National Council of State Legislatures in Washington, D.C., in December to show an excerpt of the film and discuss John’s recovery.

After his first psychiatric hospitalization, Cadigan’s family came to Pittsburgh to help him move back to California, where they lived. While they were packing, his sister Katie began filming John. “I thought [the filming] would force me to examine my life and help me to accept what was happening to me,” John said.

In one scene, a young Cadigan constructs an impossibly high pyramid of medication bottles. “During the first three years of my illness, I was pretty much sick all of the time,” he recalled. “I tried every antipsychotic, antidepressant, and mood stabilizer, but nothing worked.”

The pyramid of bottles comes crashing down.

While in his 20s, Cadigan was hospitalized repeatedly and dealt with catatonia, incessant paranoia, debilitating depression, and cognitive impairment. When he tried to read, he said, “I literally could not understand the words—it was even hard to watch TV. Basically what I did all day was pace and drink coffee.”

Alcohol Didn’t Help

Things declined even further. “I turned to alcohol and was getting drunk almost every day,” said Cadigan.

After a round of electroconvulsive therapy, Cadigan became suicidal.

Clinicians told him and his family that he was a refractory patient. Said Katie, “We were told that there was no hope for John” and that we should expect that he would need to be hospitalized at least once a year. “They all gave up.”

In the mid-1990s, Cadigan discovered newfound hope when he began taking the antipsychotic Clozapine, a medication that led to gradual improvement in his symptoms and functioning.

Despite his progress, Cadigan continued to struggle with bouts of depression, paranoid thoughts, and medication side effects—he gained 100 pounds. In the film, several scenes are devoted to the trusting relationship between Cadigan and his psychiatrist, who helps him gain insight into his paranoia.

Throughout each new stage of his illness, Cadigan relied on the unwavering love and support of family.

Family Draws Closer

A family once fractured by divorce united to help him in a multitude of ways. “My illness brought everyone together,” he said.

The film depicts Cadigan interacting with his family in many scenes, including one in which he is behind the camera asking a difficult question of them: “What has been the hardest part about my illness for you?”

“There are 100 hardest parts,” his mother replied after a moment’s hesitation. “Once I understood how much you struggled with this brain disease, and how much pain you were in, it felt unbearable for me that I couldn’t do anything to help you.”

Cadigan’s brother, Steve, recalled a time when the family went to visit John in the hospital. “You couldn’t speak,” he said. “You were trapped inside yourself and there was sheer terror in your eyes—that was really hard.”

Besides family, another critical support in Cadigan’s life is his art. At various points in the film, Cadigan is shown working in his studio, a place he feels “safe and creative,” he said.

After stenciling images and elaborate designs onto pieces of wood, he then carves the images into the wood and creates prints from them.

Cadigan’s art expresses the hope he feels about his life and illness as well as his inner turmoil.

He said he is inspired by mythological images, and through his art explores themes such as contradiction and the unconscious.

“I had a revelation one day that ultimately what all my work is about is a search for God,” Cadigan said.

At one point in the film, Cadigan vows to finish carving a two-inch by four-inch piece of wood in three year’s time—by his 30th birthday. The unveiling of the finished piece is captured in the film.

“I beat my goal,” the films shows an exuberant Cadigan telling his sister.

Cadigan told attendees at the press conference that since the filming ended, he has been doing well. “I have my ups and downs, but most of them are ups,” he said.

He is living in his own apartment and has displayed his artwork in a number of galleries and museums. In addition, he recently received his first commission to create new art, he said.

With the help of the Weight Watchers diet plan, Cadigan said he has lost more than 60 pounds.

In retrospect, he said that he found the filmmaking experience to be “therapeutic,” but getting in front of the camera when he was depressed or paranoid proved quite difficult.

“We wanted to show the reality of mental illness, so as part of our goal, I had to film those really dark times,” he said.

He and Katie’s goal in making the film, he said, was to erase the misinformation and stigma surrounding people with mental illness. “The best way I could do that was to tell my story.”

As the film’s producer, Katie said the film provided the family with “a safe place to talk about what was happening with John.”

Part of the film’s antistigma message lay “just in the fact of our family loving John,” she added.

More information about the film “People Say I’m Crazy” is posted online at www.peoplesayimcrazy.org/index.html. ▪