As Insurance Coverage Wanes, Psychiatric ERs Get Busier

In a side wing of the emergency department at St. Vincent's Charity Hospital in downtown Cleveland, a workaday quiet prevails on a morning in the middle of the week.

Glenn Currier, M.D.: “There has been a tremendous proliferation of children and adolescents presenting nationally in the emergency department.”

There is little to distinguish the place from a general emergency department (ED): a central desk with computers is surrounded by observation rooms with beds, and in a nearby room a physician is evaluating a newly admitted patient.

Yet this is not your ordinary ED, but a specialized psychiatric emergency department, and the people who arrive here have primary psychiatric disorders. Like all emergency patients at St. Vincent's Charity, they enter and are triaged through the main ED, but once admitted to the psychiatric ED, they are treated by a staff psychiatrist, one of whom is on duty during each work shift.

While the psychiatric ED occupies a separate space, it is not a stand-alone operation, and the staff psychiatrist works in consultation with staff in the general medical ED to determine the best treatment plan.

“The psychiatric ED should be a seamless part of the whole emergency department,” Philipp Dines, M.D., chair of the department of psychiatry at the hospital, told Psychiatric News. “A stand-alone might work well for patients with localized psychiatric problems, but that's not the reality of the patients who come here. The reality is that patients arrive with medical illnesses and behavioral conditions that complicate each other. I want the psychiatric ED to be truly integrated with general emergency medical care.”

ED Flags System Dysfunctions

In operation for nearly 30 years as part of the hospital's mission to serve the community's health care needs, the psychiatric ED at St. Vincent's is the only one in Cleveland and one of only two in Ohio.

A mobile crisis team that treats emergencies in the community has reduced somewhat the number of psychiatric cases arriving at the hospital, but today the psychiatric service still treats between 15 and 20 patients a day. Patients are liable to arrive from anywhere in the city and whenever they cannot find care elsewhere.

“We get a constant stream of patients from other places, and our numbers fluctuate whenever there are stresses in the local health care system,” Dines said.

In this regard, the psychiatric ED at St. Vincent's mirrors a national phenomenon: what happens in the emergency department is often the first indicator of dysfunctions in a larger system.

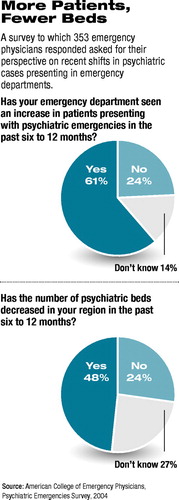

One red flag that has emerged nationally is the rising number of psychiatry patients seeking emergency care. Earlier this year a survey of emergency physicians found that 61 percent of the 353 emergency physicians who responded saw an increase in the number of mentally ill people seeking emergency care at their institutions in the previous six to 12 months (see charts). The survey, conducted online by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) with APA, the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, and the National Mental Health Association, was publicized in the March edition of the ACEP member newsletter, reaching approximately 12,000 active members.

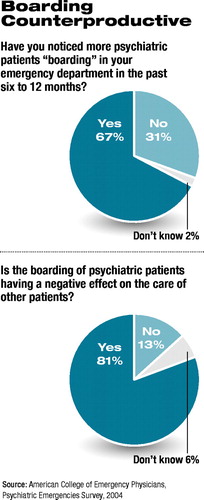

Of the 353 respondents, 62.7 percent attributed the escalation to cutbacks in state health care budgets and the decreasing number of psychiatric beds. Moreover, 67 percent reported an increase in “boarding” of people with mental illness—the practice of keeping patients in the emergency department until inpatient beds, or other places of care, are found.

Emergency psychiatrist Michael H. Allen, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, emphasized that the organization of emergency psychiatry services is highly variable from one region of the country to the next, and often from one part of town to the next.

He said that the increase in mentally ill patients seeking emergency care is related to the loss of public or private insurance: as individuals lose coverage, they are liable to lose any regular source of care they might have had.

“But the larger problem is that health insurance comes with such poor mental health benefits that it would be more accurate to count many people as effectively uninsured,” Allen said. “They can get medical but not mental health care, which then forces disproportionate numbers into the emergency system for mental health problems. All of these factors have resulted in an increase in traffic in the emergency department related to mental health care, and a general feeling [among medical emergency physicians] that they are not well organized to take care of these patients.” And that is not all that accounts for the increase.

“There has been a tremendous proliferation of children and adolescents presenting nationally in the emergency department,” said Glenn Currier, M.D., president of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry (AAEP). “In part this has been fueled by [the 1999 school shooting at] Columbine, because teachers now have a policy of zero tolerance and often bypass parents in deciding to send kids to the ED, often when subacute emergency mental health services would have been sufficient if available.”

Specialized psychiatric EDs, like the one at St. Vincent's in Cleveland, are one answer to the overflow of mentally ill patients in general medical emergency departments. The exact number of such specialized services is unknown: the American Hospital Association stopped counting several years ago, and many hospitals have hybrid services, including mobile crisis units or on-site consultation services, which blur the definition of a specialized psychiatric emergency department (Original article: see facing page).

Currier said that the most recent AHA data put the number of psychiatric emergency departments at approximately 1,500. They tend to exist in large urban settings at academic hospitals that have the resources to staff a separate service and the volume of patients to make it worthwhile. Many more hospitals—especially those in rural settings—often have a psychiatrist available only by phone.

“We know there was a trend toward the proliferation of psychiatric emergency services that followed deinstitutionalization and the emergence of managed care,” Currier told Psychiatric News.

Yet hospitals do not make money on such services: evaluation of the typical emergency psychiatric patient requires more time and resources than does a medical patient, and psychiatric EDs do not feed patients into money-making intensive care units as do general medical EDs.

Nonetheless, Allen believes the expertise that a psychiatric emergency service can offer is more cost-effective in the long run. “Medical EDs aren't organized to do diagnostic assessments,” he said. “They are organized to do triage—the sickest cases go to the hospital, and everyone else gets sent somewhere else.

“Under that model, you wind up with people being admitted to the hospital who don't need to be, while those who don't get admitted to the hospital are lost to follow-up,” Allen said. “So triage costs you more in the long run. You are better off devoting some resources at the front door, doing a good assessment, and starting treatments for people.”

Practicing High-Stakes Medicine

In an environment in which mentally ill people are increasingly seen at an acute stage of illness, the psychiatrist with a specialized interest in emergency medicine is liable to become a critical gatekeeper.

Currier reports that the AAEP has 500 members nationally, most of whom are practicing clinicians in psychiatric or general medical EDs. Several teaching centers offer informal fellowships in emergency psychiatry, and the association hopes to develop a curriculum that will serve as the basis for a formally recognized fellowship program.

Though subspecialty status is a possibility in the future, the field is likely to remain for now a stepchild of emergency medicine and psychiatry.

Though subspecialty status is a possibility in the future, the field is likely to remain for now a stepchild of emergency medicine and psychiatry.

But Currier and Allen said that treating mentally ill people in an emergency setting demands a unique set of skills and the ability to collaborate with general medical staff. It is “high stakes” medicine, in which stark decisions between admitting a person to the hospital and releasing him or her into the community must be made within a narrow window of time and often with a minimum of information.

Allen said emergency psychiatrists must be especially good at assessing risk and determining the level of dangerousness to self or others. “Day in and day out, the emergency psychiatrist deals with patients who may have intense suicidal ideation but about whom the psychiatrist may have no prior knowledge,” he told Psychiatric News. “Your assessment has to be finely tuned to that window of time, and the stakes are pretty high. So the emergency psychiatrist gets good at listening carefully and using his or her intuition about people.”

As Currier observed, it is a psychiatrist's name that is liable to be on the order that releases a patient into the community after ED assessment and treatment. So where a patient goes afterward is critical, and emergency psychiatry requires outreach to the community to which a patient will return.

At St. Vincent's Charity Hospital, the patient or visitor emerging from its doors looks out across Interstate 90 at Jacob's Field and the Terminal Tower on Cleveland's downtown skyline. Located in the heart of Cleveland, the hospital is bounded by the Central and Slavic Village neighborhoods and by Cleveland's Industrial Valley.

In addition to the inpatient psychiatric service, St. Vincent's Charity is home to Rosary Hall, which offers inpatient detoxification and outpatient addiction recovery programs, as well as inpatient and outpatient geropsychiatric/medical services.

But Dines said more psychiatry services are needed in the community.“ People have an unrealistic view of the ED,” he said. “They think, `This person is mentally ill, and he's going to go to the emergency department and get better.' But the ED is only the beginning, only scratching the surface. The psychiatric ED is a useful model, but it is only as strong as our ability to connect to the community.” ▪