Storied Neighborhood Emblematic Of Immigrant Experience

Walk around New York City neighborhoods long enough, and you are liable to wander, unaware, through some sites of notable social or cultural history that time has transformed, obscuring a vivid and rambunctious past.

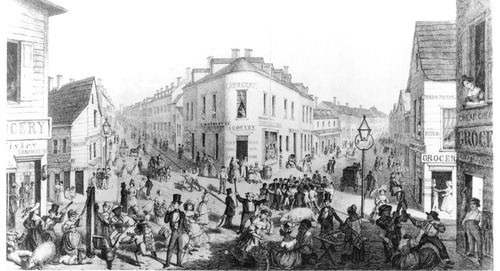

One of those places is in what is now Chinatown, at the intersection of Orange, Cross, and Anthony streets in lower Manhattan—a crossing whose five corners gave the name to the 19th century neighborhood known as Five Points. The notorious character of the neighborhood and importance as a landmark in the American immigrant experience are captured in Tyler Anbinder’s 2001 book, Five Points: The 19th Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum.

One of those places is in what is now Chinatown, at the intersection of Orange, Cross, and Anthony streets in lower Manhattan—a crossing whose five corners gave the name to the 19th century neighborhood known as Five Points. The notorious character of the neighborhood and importance as a landmark in the American immigrant experience are captured in Tyler Anbinder’s 2001 book, Five Points: The 19th Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum.

The account, a New York Times Notable Book, is published by Penguin Putnam Inc.

The Five Points neighborhood was a hotbed of vice, decrepit living conditions, and shenanigans of all kinds—so much so that touring the neighborhood became a kind of international attraction for those wanting to see the underside of the American Dream. But as Anbinder recounts, the story of Five Points is greater than the sum of its pathologies.

“Five Pointers’ stories are as old as America itself, and yet as contemporary as the current waves of immigrants that continue to reshape our society,” he writes.

Anbinder recounts the history of Five Points from its origins in the late 1700s as a site of slaughterhouses, meat-packing factories, and tanneries—industries whose noxious fumes and reliance on cheap, unskilled labor set the stage for an inexorable decline. As immigration swelled the city in the 1820s and 1830s, the small buildings that had dotted the neighborhood gave way to apartments and tenements, rented to African Americans and waves of poor immigrants—from Ireland, especially, but also from Italy, Germany, and Eastern Europe.

By the 1830s, the neighborhood’s “disreputable fate” was sealed when it became a center of prostitution. By this time, the press had begun to refer to the neighborhood as Five Points and to chronicle its crime and squalor. In 1834, what Anbinder calls “a full-scale racial pogrom” broke out when antiabolitionists rampaged through the neighborhood attacking African-American homes, businesses, and churches.

Later that year and the next, riots rocked the neighborhood again. “They revealed racial, ethnic, and religious fault lines that New Yorkers had previously recognized but preferred to ignore,” Anbinder writes. “Over the next 65 years, Five Pointers would often find themselves at the epicenter of the struggles—ones that would help shape modern New York.”

For all its troubles, Five Points was also a place where America’s newest citizens built the foundations of better lives for children who would escape the neighborhood. Anbinder documents the lives of some of these strivers.

For many immigrants the conditions in Five Points were actually an improvement over what they had left. Anbinder pays particular attention to Irish immigrants who had left the Lansdowne estate, a farm in Ireland that was blighted by the potato famine in the 1840s. The appalling conditions on the plantation, the dire physical condition to which the farmers were reduced, and the difficulty of their journey across the ocean are richly documented.

So Five Points became a home. “By the time the potato blight struck Ireland, Five Points was known throughout the English-speaking world as a veritable hellhole,” Anbinder writes. “Yet the Irish who settled there during the famine years had seen far worse, going months and sometimes years without work and watching friends and family starve before their eyes. The Irish did not come to Five Points expecting streets paved with gold. They simply wanted work—work that would enable them both to feed their families and to put a little something away so that someday their children could have a better life.”

Five Pointers also played hard. There was a carnival atmosphere to Five Points, with the Bowery on the neighborhood’s eastern edge the center of the spectacle.

Walt Whitman extolled the Bowery as “the most heterogeneous mélange of any street in the city; stores of all kinds and people of all kinds are to be met with every forty rods. . . .You may be the President or a Major-General, or be Governor, or be Mayor, and you will be jostled and crowded off the sidewalk just the same.”

The Bowery was home to the Bowery B’hoys, a subculture of dandy-toughs that flourished for a while by making a name for themselves as lovers of adventure and excitement. (Bowery B’hoys were touted for acts of courage during the Mexican War and were among the first New Yorkers to leave for California during the gold rush.)

A number of inexpensive playhouses sprouted on the Bowery and Chatham Street that catered to the working class, and bare-knuckle prize fighting, among other spectacles, became a Five Points trademark.

After the Civil War, the neighborhood changed, and by 1890 even the name Five Points had dropped from usage. Reform efforts by missionary groups, out-migration of residents to better sections of the city or the country, and the depletion of the male population by the Civil War had changed the face of the neighborhood.

Today, the only 19th century immigrant group that has stayed in the neighborhood is the Chinese. Five Points, Anbinder writes, has become Chinatown.

The story of Five Points is emblematic. “From 1607 to 2001 and beyond, would-be Americans have arrived from abroad, adjusted to the often harsh realities of their lives, and set to work,” Anbinder writes. “The Five Points story, at a certain level, is common to us all. . . . There may never again be another slum quite like Five Points, but as long as the United States remains a nation of immigrants, the outline of the Five Points story will never die.”

Ordering information for Anbinder's book, Five Points: The 19th Century New York City Neighborhood That Invented Tap Dance, Stole Elections, and Became the World’s Most Notorious Slum, is posted online at www.penguinputnam.com/Book/BookFrame/0,1007,,00.html?id=0452283612. Additional information on the Five Points neighborhood is posted online at http://r2.gsa.gov/fivept/fphome.htm. ▪