Brain Data Reveal Why Psychotherapy Works

Mounting evidence on psychotherapy shows that it is effective and can even alter the brain’s chemistry.

This was the message delivered by researchers and educators at the daylong seminar “Scholarly Activity in Psychotherapy Training,” which was held in conjunction with the annual meeting of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) in New Orleans in March.

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the meeting, and partners included APA’s Commission on Psychotherapy by Psychiatrists, APA’s Committee on Research, and AADPRT.

Lisa Mellman, M.D., one of the session chairs, told Psychiatric News that evidence presented during the meeting “furthers our ability as educators to teach residents to become psychotherapists.”

For people with mental illness, psychotherapy affects the brain’s neural networks in much the same way that medicines do, according to Ari Zaretsky, M.D., head of the Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Clinic at Sunnybrook and Women’s College Health Sciences Centre and an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto.

“Many people view psychotropic drugs as the potent interventions, as if they are the biological intervention and psychotherapy is not,” said Zaretsky.

Psychotherapy Alters Brain

Zaretsky presented evidence that different forms of psychotherapy can alter the brain’s processes for patients with different types of psychiatric disorders in much the same way that antidepressants do.

For those with psychiatric illnesses, the “experiential learning” from cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to alter some of the same biological mechanisms typically affected by medications, Zaretsky said.

For instance, it is known that for depressed patients, an antidepressant response is associated with a 5 percent to 20 percent reduction in thyroid hormone levels. When Russel Joffe, M.D., and colleagues measured the thyroid hormone levels of 30 depressed patients before and after 20 weekly sessions of CBT, they found significant decreases in T4 levels for the 17 patients for whom CBT ameliorated depressive symptoms. Moreover, he found increases in T4 levels for the 13 patients who did not respond to CBT. The study appeared in the March 1996 American Journal of Psychiatry.

“We don’t really know why thyroid levels decrease in people who respond to an antidepressant treatment,” Zaretsky said, “but it seems to be a marker for depression improvement.”

Scans Reveal Improvement

The effects of psychotherapy on the brain can also be detected in other ways, Zaretsky noted.

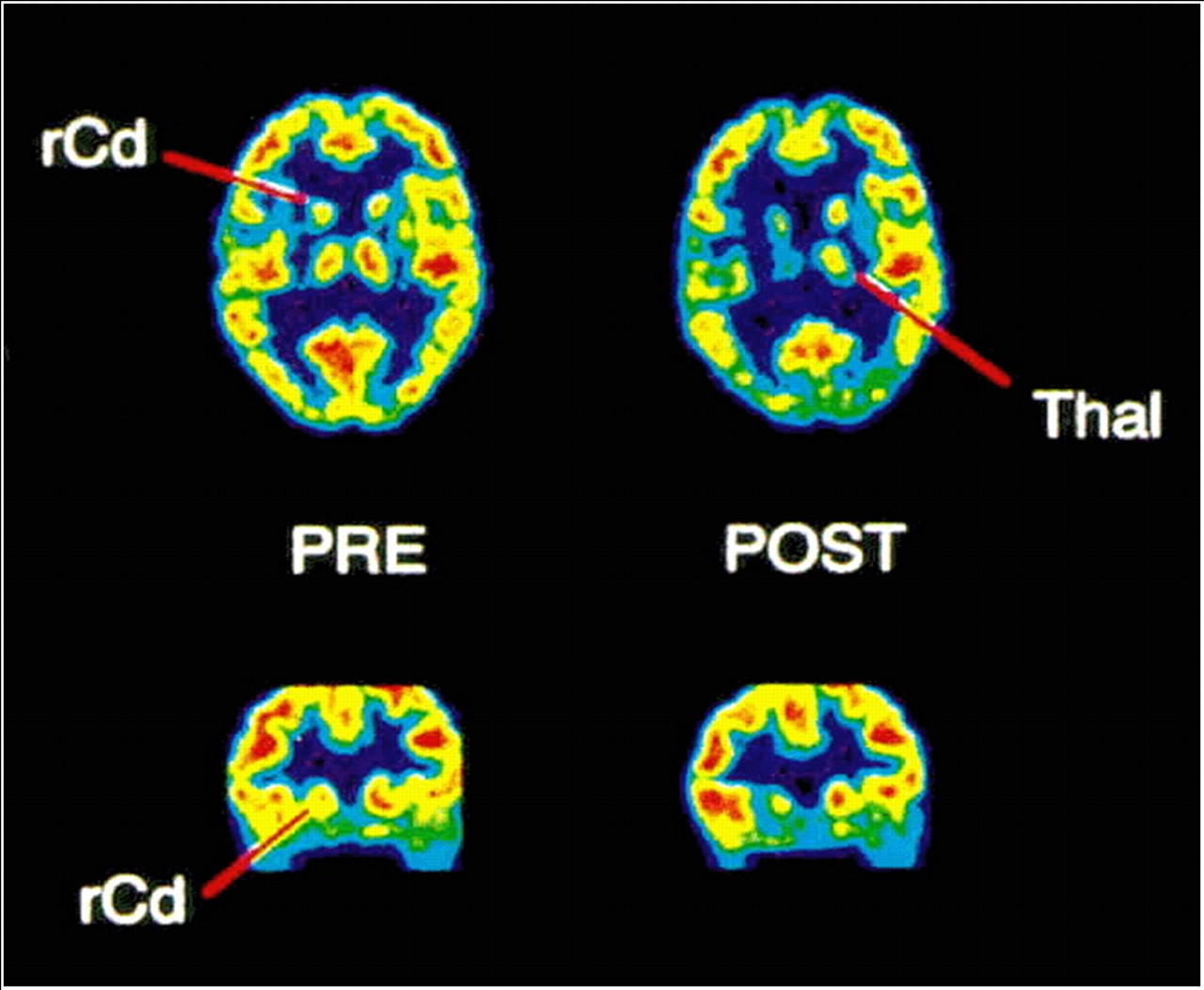

Above are PET scans of a patient with obsessive-compulsive disorder who responded to behavior therapy. The scans at left were taken before treatment; the scans at right were taken after two months of therapy. Decreases in glucose metabolic rates are particularly striking on the right.

The scans show decreases in glucose metabolic activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and right caudate after both the therapy sessions and the medication treatment.

The orbitofrontal cortex, Zaretsky explained, “seems to be a part of the brain that signals to us that something is wrong in the environment.”

In the case of people with OCD, he said, excessive metabolic activity in this part of the brain creates faulty error signals that impair the person's ability to perceive and interpret factors in their environment correctly

“Behavioral therapy can reduce these faulty error signals, and this is reflected in the scans,” Zaretsky said.

Same Results, Different Route

Zaretsky also cited recent research by Helen Mayberg, M.D., and colleagues, who used PET scans in 17 unmedicated patients with major depression before and after they had 15 to 20 sessions of CBT.

She compared the scans with those of 13 patients who were already successfully treated with paroxetine alone.

Mayberg’s group found that CBT reduced depressive symptoms as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale for 14 patients and that treatment response was associated with increases in metabolic activity in the hippocampus and anterior cingulate and decreases in metabolic activity in the dorsal, ventral, and medial frontal cortices.

However, in patients who responded to paroxetine, metabolic activity increased in the prefrontal cortex and decreased in the brainstem and subgenual cingulate.

The article appeared in the January issue of the Archives of General Psychiatry.

Said Zaretsky, “This fascinating study showed that although CBT and paroxetine seemed to improve depression to the same degree, they did so by acting on different brain circuits—CBT seems to work top-down, whereas pharmacotherapy works more bottom-up.”

Zaretsky said future research should focus on how certain types of psychotherapy affect the brains of children or young adults who are at risk for serious mental illness and “how longer-term psychotherapy alters the neural networks of self-representation or core beliefs” in patients with personality disorders.

“Teaching medical students about how psychotherapy can change the brain may draw them in greater numbers to psychiatry, he surmised, and would “reintegrate psychotherapy, which has been viewed as an art, into medicine—a scientific discipline.”

Is Intensive Therapy Better?

Although the terms, “evidence-based” and “psychodynamic therapy” don’t often appear together, there is some early scientific evidence supporting the efficacy of different types of dynamic psychotherapy, maintained Jacques Barber, Ph.D., a professor of psychology and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Psychotherapy Research.

However, in regard to psychoanalysis and long-term dynamic therapy, much of the evidence is preliminary, and problems with methodology may hamper the strength of the findings, he pointed out.

For example, “most studies of long-term dynamic therapy don’t randomize patients to treatments or use control groups,” Barber explained. Nevertheless, he said, there is relatively strong evidence suggesting that “more-intensive treatment often leads to better outcomes than does less-intensive treatment.”

One example is the 1989 Heidelberg Long-Term Therapy Follow-Up Project in which psychotherapy researcher Hans Kordy, Ph.D., compared outcomes for 36 patients receiving psychoanalysis three times a week with those of 33 patients receiving less-intensive dynamic therapy once a week for 2.5 years.

Kordy found that 71.9 percent of the patients receiving psychoanalysis demonstrated “good success” in terms of achieving their goals in the therapy sessions, compared with 50.5 percent of those in long-term dynamic therapy.

Although the study’s findings are intriguing, Barber said, its methodology was less than perfect. “Patients were not randomized to treatment groups, so we don’t know, for example, if a different type of patient received psychoanalysis.”

Similar Results Found for Depression

Many psychiatrists and mental health professionals assume CBT is more effective than dynamic psychotherapy, especially in treating patients with depression, Barber said, but there is no such evidence.

He cited research by Falk Leichsenring, D.Sc., from the University of Göttingen in Germany, who compared outcomes from six studies in which patients received short-term dynamic psychotherapy or CBT for depression. The results of Leichsenring’s study appeared in the April 2001 Clinical Psychological Review.

When he compared depressive symptoms, social functioning, and overall improvement among patients receiving either type of treatment, he found no significant differences.

Two years later, Leichsenring examined findings from 14 studies in which patients with personality disorders received psychodynamic psychotherapy and 11 studies in which patients with personality disorder received CBT. Some of the studies were controlled and randomized, and some were naturalistic, Barber said.

Leichsenring concluded that both types of therapy are effective in treating patients with personality disorders. The findings appeared in the July 2003 American Journal of Psychiatry.

Barber suggested that an interesting clinical and research problem is to define subgroups of patients who do better with dynamic psychotherapy and those who do better with CBT. He acknowledged that much more research is needed to determine the efficacy of dynamic therapy in different populations, such as young people with depression, for whom antidepressants might not always be the best option.

CBT Put to the Test

A primary assumption of CBT is that the way a person perceives the world will shape his or her feelings, said Joel Yager, M.D., professor and vice chair for education and academic affairs at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine’s department of psychiatry.

Clinicians conducting CBT seek to increase patients’ awareness of their dysfunctional cognitive appraisals, Yager said, and to “educate patients as to how these appraisals can generate negative emotional and maladaptive behavioral responses.”

Ultimately, clinicians teach patients to develop, learn, and incorporate a variety of effective self-management skills, he added.

CBT has been studied and used in the treatment of a wide variety of psychiatric disorders, including depression, panic disorder, and bulimia—for which it has been shown to be very effective—and generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder, for which CBT has been shown to be moderately effective, Yager pointed out.

Yager examined more than 100 studies evaluating the efficacy of CBT and concluded that while it is often better than usual care for many patients, it is often not much more effective when compared with other types of psychotherapy, such as interpersonal psychotherapy, active supportive therapies, or dynamic psychotherapy.

One of the studies he examined appeared in the May 2003 American Journal of Psychiatry. The author, Gordon Parker, M.D., D.Sc., a professor of psychiatry at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, and colleagues undertook their own meta-analysis of studies of CBT in the treatment of acute depression and found that its superiority over other types of psychotherapy, such as interpersonal therapy (IPT), is to some extent unproven.

Results Are Mixed

When Gordon looked at CBT for the ongoing treatment of depression, he found that although there is some evidence of efficacy for preventing relapse after antidepressants are tapered, “it is unclear what CBT adds to ongoing medication,” Yager said.

Other researchers have arrived at different conclusions, Yager noted. For example, Martin Keller, M.D., randomly assigned 681 adults with a chronic major depressive disorder to 12 weeks of outpatient treatment with nefazodone, 16 to 20 sessions of CBT, or both. He found that depressive symptoms decreased by 48 percent in patients who received either CBT or nefazodone alone, but by 73 percent in the combined-treatment group.

Data about what types of patients best respond to CBT are mixed, Yager said, but there is some suggestion that it works best for patients with an external locus of control or who attribute success or failure to circumstances beyond their control, such as to fate or chance. ▪