When Mental Illness Makes News, Facts Often Missing in Action

Newspaper stories about mental illness still focus most commonly on danger and crime, according to a study of 3,353 articles in 70 major U.S. dailies.

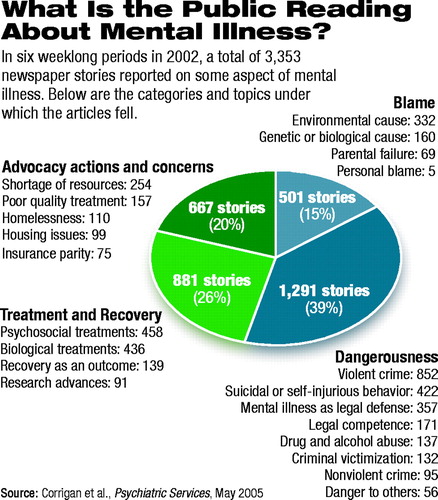

Thirty-nine percent, or 1,291, of the stories fell under the danger heading, most of them in the front section of the papers surveyed, said researchers led by Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., of Evanston Northwestern Healthcare, in the May Psychiatric Services. At the same time, 26 percent of the stories dealt with treatment and recovery, and 20 percent covered advocacy actions and concerns.

The 39 percent of the stories related to dangerousness was smaller than the 50 percent to 75 percent reported in earlier research, wrote Corrigan and colleagues.

“From this survey, we discovered that stories about danger and crime are waning, although they are still the largest single focus among stories about mental illness,” they stated.

Nevertheless, Corrigan sees the glass of stigma as half full, if 3 out of 5 stories do not use disrespectful language about mentally ill individuals.

“This is an improvement over the status quo,” he said in an interview. “It's good to hear that coverage of stigma is moving in the right direction, although the public is still being influenced with messages about mental illness and dangerousness.”

The researchers selected all daily newspapers in the U.S. with a circulation greater than 250,000, plus the largest newspaper in any state where no paper's circulation reached that figure. The average daily circulation of the 70 papers was about 451,000, ranging from 16,755 to 2,195,805. They searched online databases for the 70 papers using the terms“ mental,” “psych,” and “schizo.” Articles dealing only with drug or alcohol abuse were not included.

The stories were identified and coded during six weeklong periods in 2002. The coding system was based on the authors' previous research and had four main categories: dangerousness, blame, recovery, and advocacy action. Some stories could fall into more than one category.

Within the danger category, the most common references were to violent crime, suicidal or self-injurious behavior, or mental illness as a legal defense. In contrast, only 56 of the 1,291 articles under the danger heading focused on mental illness as a danger to others, and 132 connected mental illness with being victimized by crime.

Of the 3,353 articles that mention mental illness, 13 percent referred to biological treatments and 14 percent to psychosocial treatments, but only 4 percent considered recovery as an outcome.

“The news media may not be adequately informing the public about the role of recovery in treatment,” wrote Corrigan and colleagues.

Only 15 percent of the stories (501) addressed blame or causation. Almost none blamed the mentally ill individuals or their parents for their condition. Mental illness was most often ascribed to environment, genetics, or biology.

Advocacy issues, addressed in 20 percent of the stories, largely focused on shortages of resources and poor quality of care. Only 75 articles out of 3,353 dealt with insurance parity.

Corrigan said that future research ought to review coverage of mental illness both in smaller local newspapers and on radio and television. A more complex analysis might be helpful as well.

“They must also examine how the form of the information (printed word and picture compared with sound bite compared with video) has an impact on the message,” he said.

One way to continue the trend he discerns in mental health coverage might be to increase coverage of ways to help mentally ill people, he said. “I would hope that reporters would write more about what the community can do to improve their status and care.”

But getting the news media to understand mental health issues and reduce stigmatic portrayals of mentally ill individuals is no simple task, said epidemiologist Heather L. Stuart, Ph.D., of Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, in an interview. Stuart documented the effects of an intervention with a daily newspaper in Calgary several years ago.

Positive stories about mental health outnumbered negative ones by 2 to 1 both before and after the intervention, which included giving reporters more accurate background information and inviting an editorial writer to participate in an antistigma action team. However, negative coverage increased after the intervention, probably because there were several murders committed during the same period by persons identified as “untreated schizophrenics.”

“You just have no control over that,” said Stuart. “They don't even have to be local crimes. People see or read about terrible things happening in Japan or at Columbine.”

Formal programs to intervene with local media are unlikely to help much, she said. Instead, she recommended offering fact-based information for the online background file that most papers maintain today; suggesting—in advance—expert sources, both patients and doctors; and maintaining informal channels of communication.

“Take a reporter to lunch every couple of months,” she advised.“ If you approach reporters in a positive way, you can find listeners. Establish trust and friendship, and then hope they develop a mutual interest in mental health.”

This could pay off for all involved, said Stuart. One reporter won an award from a Canadian mental health organization for a series of articles on schizophrenia.

Perhaps even more important are stories that should address mental health issues but never mention the subject, said former New York Times correspondent Catherine S. Manegold, now the James M. Cox Jr. Professor of Journalism at Emory University in Atlanta and a member of the advisory board for the Rosalynn Carter Fellowships for Mental Health Journalism.

“Reporters and editors just miss it,” she said in an interview.“ They might mention poverty or other factors that underlie a story, but miss the ball entirely on mental health issues. It's easy not to think it through when you're on deadline.”

Such articles would be hard to find and quantify because the keywords would not be visible to researchers, she said.

Newspapers generally do not have policies regarding mental health stories, said Manegold. But reporters who know or meet someone with mental illness may develop an interest in the area and write about it with accuracy and sympathy. Their ideas will percolate around the newsroom as fellow reporters read their stories and thus improve coverage.

“Newspaper Stories as Measures of Structural Stigma” is posted online at<http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/56/5/551>. Stuart's paper, “Stigma and the Daily News: Evaluation of a Newspaper Intervention,” is posted at<www.cpa-apc.org/Publications/Archives/CJP/2003/november/stuart.asp>.▪

Psychiatr Serv 2005 56 551