Telepsychiatry Bridges Gap In Indian MH Care

Practicing psychiatry hundreds of miles away from your patient over a video link means marrying technology and medicine with mundane subjects like funding and credentials, said Jay H. Shore, M.D., M.P.H., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center in Denver (UCHSC), at APA's 2005 annual meeting in Atlanta.

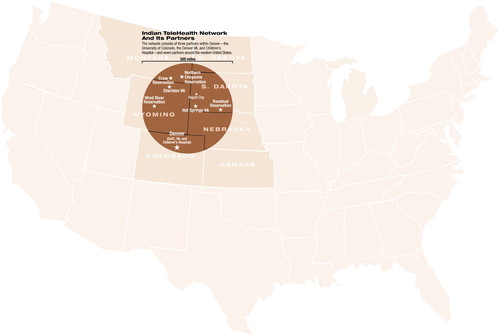

The center runs telepsychiatry programs from Denver serving American Indian patients hundreds of miles away in several surrounding states. These services include a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) clinic for north Plains Indian military veterans and a child and adolescent consulting practice at a South Dakota hospital.

Both services operate with the University of Colorado psychiatrists in a room in Denver, while the patients go to sites equipped with a video linkup near their homes. The Indian Telehealth Network uses an integrated digital services network (ISDN) or a Department of Veterans Affairs intranet, not the open Internet.

“Video conferencing over the Internet is not secure, the quality is not that good, and it varies with the amount of traffic,” said Douglas K. Novins, M.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at UCHSC. “ISDN gives us much better quality.”

Remote setups for veterans are located at clinics on the Rosebud, Wind River, Crow, and Northern Cheyenne reservations. Trained outreach workers like Gilbert Jarvis help persuade tribal members suffering from PTSD to come to the local clinics for evaluation and therapy. Contemporary telepsychiatry is integrated with a native-healer program that uses sweat lodges, talking circles, and healing ceremonies, said Jarvis, a Shoshone tribal outreach worker and a veteran well connected to the veteran community in rural Wyoming.

“Indian culture says you can't let other people know your problems,” said Jarvis, who appeared with the UCHSC doctors in Atlanta. Many would fear exposure if they were seen coming out of a mental health clinic, but are willing to visit a Veterans Affairs center with the proper encouragement, he said. American Indians served in disproportionately large numbers in the military and have had greater exposure to trauma and higher PTSD rates than the U.S. norm, he added. Distance creates a barrier to care because so many also live in remote areas, but outreach workers like Jarvis can connect with the vets and get them to the clinic door.

“We have one 83-year-old who thinks he's a movie star,” said Jarvis.

Service Has Built-In Advantages

In the weekly telepsychiatry clinics, the psychiatrists in Denver provide individual therapy, group therapy, and medication management, said Shore. They may take two hours to evaluate a new patient, half an hour for a follow-up session, or one hour for a weekly group therapy session. The program has logged 1,000 patient contacts in two years.

“The biggest goal in the first session is developing rapport with the patient, even if we're not getting at all the issues,” said Shore.“ Trust is critical.”

The tribal outreach workers like Jarvis help with “system transference,” vouching for the doctor and cementing the therapeutic relationship. In some ways, the distance between doctor and patient may even help, said Shore: “You won't run into the patient in the grocery store.”

The physicians may miss some subtle cues by not being in the room, but they may gain objectivity, he said. Doctors can tolerate more intense affect: the patient may get angry, but therapy needn't stop. Nonetheless, they must establish protocols covering what to do when the line goes down in the midst of a session with a suicidal patient.

Service Fills Gap for Child Psychiatrists

The separate child psychiatry program operates in cooperation with the Sioux San Hospital in Rapid City, S.D. A former Public Health Service tuberculosis sanatorium, Sioux San is operated by the federal Indian Health Service. Sioux San's last child psychiatrist left in 2001 after eight years. Currently, no child psychiatrists work for the Indian Health Service in North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, and Nebraska, the four states Sioux San serves.

Obstacles to telepsychiatry arose when it was first proposed after 2001, said Novins. The hospital could offer no funds to support the program, but federal funds were found for a pilot demonstration project, and the project moved ahead.

The UCHSC group hesitated to provide direct child psychiatric services at first. However, the Sioux San staff was experienced in general psychiatry and envisioned telepsychiatry as adding specialist expertise to its own work.

“For us, the telepsychiatry program essentially serves as a second opinion,” said adult psychiatrist Mark Garry, M.D., Sioux San director of behavioral health, in an interview. “We usually have pretty good idea of what's happening with a patient, but the system can confirm that or offer a different opinion or treatment plan.”

Patients in Rapid City have already seen Garry or another psychiatrist before the telepsychiatric consultation. Each patient receives an 80-minute initial evaluation by the UCHSC team assessing the child and a caregiver. Those sessions are followed by 40-minute case discussions with local doctors, nurses, and social workers. The telepsychiatry group performed 21 evaluations in its first year, most extremely complex, given Sioux San's status as a tertiary hospital, said Novins.

“Patients and caregivers said it helped to have their own clinician in the room and to know that an expert was involved,” said Novins.“ Clinicians reported that the UCHSC group helped with diagnoses. They learned by watching the child psychiatrists and felt less isolated and more comfortable seeing these patients.”

The child psychiatrists in Denver said they took longer to establish rapport with patients over the video link and found the session less emotionally satisfying and harder to remember. There was an average of one disconnection per session, which added to the sense of discontinuity, said Novins.

Technical problems remain the biggest concern for Garry in Rapid City, who recounted three line failures in one session on the day he spoke with Psychiatric News. “You can be in a long, sensitive discussion with a patient when the line goes down, so you need a technical person who can get things reconnected quickly.”

He noted, however, that he and the other general psychiatrists at Sioux San can usually maintain the discussion in the room during any outages.

Technical issues aside, patients and their families say they are satisfied with the program. Adolescents sometimes relate to the screen and camera even better than to a clinician in the room, said Garry. “They look at it like another video game.”

Some Barriers Remain

The operating costs of the UCHSC telepsychiatry system were less than six face-to-face consultations a year ($744 versus $932), but the $8,500 in initial equipment costs represented a significant difference. Allocating those hardware costs among other disciplines would ease the financial burden.

“It's hard to convince other UCHSC providers to use the system,” said Shore. “If we could spread the fixed costs across multiple clinics, the cost per unit would drop.”

Although the demonstration funds ran out in February, Sioux San eventually funded the fixed costs and uses the equipment to consult with a small Indian reservation.

Money is only one issue that must be addressed for telepsychiatry to work, said Shore. Nearly as much administrative time goes into the project as clinical time, he said. Licensing for physicians working across state lines is another question. Psychiatrists treating veterans can sidestep that since they fall under the federal umbrella, but some system of shared state licensing, national licensing, or limited telemedicine licensing is needed in the long run, he said. Integration inside and outside the system is essential, he added.

“You need to develop both the technology and the program in parallel,” he said. “And you need cooperative, dedicated people at both ends.”

Further information is posted online at<www.uchsc.edu/ai/cnatt/cnattindex.htm>.▪