Varying Standards Characterize Industry-Academia Relationship

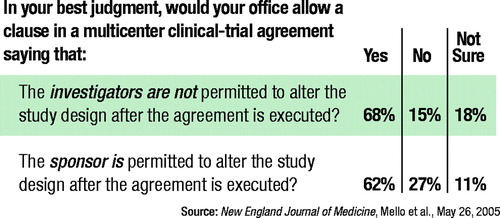

Standards for certain restrictive provisions in clinical-trial agreements with industry sponsors vary among academic medical centers, according to a survey of medical-school research administrators responsible for negotiating clinical-trial agreements with industry sponsors.

Greater sharing of information about legal relationships with industry sponsors is desirable to build consensus about appropriate standards, said Michelle Mello, J.D., Ph.D., lead author of the report, which appeared in the May 26 New England Journal of Medicine.

Although industry sponsors provide approximately 70 percent of the funding for clinical drug trials in the United States, little has been known about the related legal agreements between industry sponsors and academic investigators.

The investigators mailed a structured survey to administrators at 122 institutions, 107 of whom participated in the survey.

Mello and colleagues found a high degree of consensus among administrators about the acceptability of several contractual provisions relating to publication of research findings. For example, more than 85 percent reported that their office would not approve provisions giving industry sponsors the authority to revise manuscripts or decide whether results should be published.

However, there was considerable disagreement about the acceptability of provisions allowing the sponsor to insert its own statistical analyses in manuscripts. On this question, 24 percent of respondents allowed them, 47 percent disallowed them, and 29 percent were not sure whether they should allow such provisions.

There was also some variability in the acceptability of provisions allowing the sponsor to draft the manuscript (50 percent allowed it, 40 percent disallowed it, and 11 percent were not sure whether they should allow it) and prohibiting investigators from sharing data with third parties after the trial is completed (41 percent allowed it, 34 percent disallowed it, and 24 percent were not sure whether they should allow it).

Disputes were common after the agreements had been signed and most often centered on payment (75 percent of administrators reported at least one such dispute in the previous year), intellectual property rights (30 percent), and control of or access to data (17 percent).

“The heterogeneity of acceptability judgments among our respondents raises the possibility that industry sponsors could `forum shop,' channeling their studies to relatively permissive institutions,” Mello and colleagues said. “However, the degree of heterogeneity was relatively small for some critical issues, such as whether sponsors could impose an absolute publications bar, and in general, the data did not demonstrate strong associations with observable institutional characteristics such as the volume of clinical research and the percentage of research funding obtained from industry.”

They added, “The lack of clear indicators of permissiveness may frustrate attempts to forum shop, although sponsors could still learn from experience, word of mouth, and institutional culture and leadership that countenanced permissive relationships with industry.”

Robert Freedman, M.D., editor-designate of the American Journal of Psychiatry, said that the issues raised in the NEJM article are well known within the research community, but he emphasized the high degree of compatibility across institutions, rather than the variability.

“What I find reassuring about the article is that the majority of academic institutions subscribe to similar standards in their contractual interactions with pharmaceutical companies,” he said. “A high degree of integrity is necessary for public confidence in the results of clinical trials conducted under such collaborations.”

More problematic are the practices of commercial contract research organizations that “generally do not have oversight by governing boards, such as boards of trustees, that can set policies for contracting,” he said.

Freedman added that peer-reviewed journals, through the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, have enacted uniform standards for reporting results of medical research that address many of the issues raised in survey by Mello.

“For example, the senior author on a collaborative study must certify that he or she has access to all of the data and wrote the paper,” Freedman said. “In addition, through the Institute of Medicine, an agreement between the journals and the pharmaceutical companies was recently reached to register all clinical drug trials beyond Phase 1 on public databases such as<clinicaltrials.gov> before their initiation, to allow comparison of what is being reported with the original design of the trial. This process prevents companies from altering the plan for analysis of data after the completion of the trial.”

The American Journal of Psychiatry subscribes to this policy, Freedman said.

An abstract of “Academic Medical Centers' Standards for Clinical-Trial Agreements With Industry” is posted at<http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/352/21/2202?>.▪

N Engl J Med 2005 352 2202