Gulf Coast Psychiatrists Report From Front Lines

“Are you evacuating?” a patient asked Harold Ginzburg, M.D., J.D., M.P.H., over the phone on the Sunday morning before Katrina hit on August 29. Like many others in the Crescent City, Ginzburg thought he had seen it all when it came to hurricanes.

“I never evacuate,” replied Ginzburg, who spent 20 years in the Navy and the Public Health Service, much of it dealing with disaster medical planning.

That was about to change in the face of Katrina's winds and high water. In New Orleans, along the Gulf Coast, and at sites where residents fled, medical services were first disrupted and doctors dispersed. Once the storm passed, medical care was organized by disaster relief organizations or by physicians, nurses, and others on the spot, wherever that happened to be. What follows are snapshots of that effort to care for those most acutely affected by the storm.

“I think you should evacuate,” said his caller firmly, so Ginzburg copied his patient and business records onto a CD, tossed underwear and socks into the same red rucksack he had lugged around the world for years, and headed out of town. He ended up at Jacob's Camp, a summer camp outside Utica, Miss., with 250 fellow evacuees and became what he had always preached—“a doctor without electricity.”

Psychiatry under field conditions called for pragmatic adaptability.

“You need to allow people to grieve without labeling them mentally ill,” said Ginzburg. “Giving them reassurance and some productive work around the camp can help them become resilient. If I can't get a patient to smile, I know I have a problem.”

Ginzburg was the only doctor, but there were nurses, social workers, and counselors among the evacuees. Utica has no physician, but the town's pharmacist offered his stock of drugs.

“I could use phenobarbitol and Dilantin or Dilantin and phenobarbitol,” he said. The only psychoactive drugs were out of another era as well: Stelazine, Thorazine, and Haldol. The drugstore did not carry oxygen, so when two patients ran out, Ginzburg trekked down to the local welding supply shop and negotiated for a bottle of industrial O2.

Psychiatrist Lawrence Hipshman, M.D., M.P.H., spent 10 days after Hurricane Katrina sleeping on baggage carousel 8 at Louis Armstrong International Airport in New Orleans.

“Room service at this hotel is really terrible,” he said dryly.

The airport served as a way station for evacuating the victims of Hurricane Katrina by air or bus. Hipshman helped triage and stabilize the newly displaced persons before they moved out of the airport and across the country.

“We've seen the whole gamut,” said Hipshman, a clinical assistant professor of preventive medicine at Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland and a member of the Oregon Disaster Medical Team.“ There are patients with preexisting mental illness who are coming off their medications, so their underlying illness is showing,, up and is worsened by the events they've experienced.”

Many others were understandably pushed to the edge first by the hurricane and flood and then by appalling conditions where they had sought shelter before being taken to the airport, he said. “Some had anxiety, acute stress reactions, or some sort of adjustment disorders,” he said.“ Some were nearly suicidal, they were so distraught. Substance abusers were either intoxicated or in withdrawal. People were overwhelmed by conditions inside the Superdome and were in a prolonged state of agitation and panic. They felt abandoned and devastated.”

His job involved more than prescribing, he said. “Part of what I did was wander around just talking to people waiting to be moved, just offering some humanitarian contact, letting them know they're safe and cared for.”

Hipshman's second task was helping the helpers—personnel from the police, National Guard, Air Force, emergency medical teams, and others. The scale of the disaster led many into emotional difficulties perceived by themselves or others.

“This was not like seeing a car crash scene,” he said.“ They saw people with nothing—no food, no clothes, no home. They saw death and trauma, and they found it hard to manage their sense of being overwhelmed. They got teary-eyed and had to take a break. It was hard for them to accept that they were not in complete control.”

The medical team was well supplied with general medications but had a limited supply of psychoactive drugs. While that amount was adequate for the acute phase of the emergency, it was not enough for the next stage—when existing prescriptions ran out. Donations from pharmaceutical companies expanded their selection.

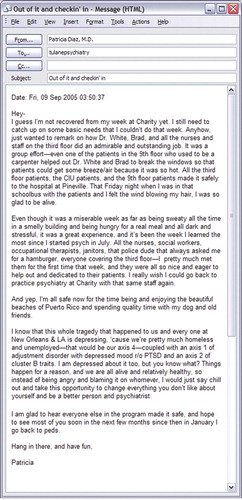

Resident Patricia Diaz, M.D., spent August 27, the Saturday night before Katrina hit, in the crisis-intervention unit at Charity Hospital watching television reports of the storm's progress and decided to stay with the 100 patients left in the hospital. When the storm hit on Monday, the power went off, as the generators in the basement were flooded. The Tulane University Medical School Internet server went down and phone service died, but tech-savvy residents figured out how to use their still-functional beepers to send text messages to the outside world. With no air conditioning and running water to flush away waste, the hospital was soon hot and foul smelling (see box at left).

“Many psychotic patients were so out of it that they didn't know what was going on until we showed them the flood out the windows,” said Diaz, who is in her second year of a combined psychiatry, pediatrics, and child psychiatry residency at Tulane.

Staff and patients lived on cold canned food from the hospital commissary, although some patients kept demanding hot meals. “They got a little desperate because they were out of touch with families and had no television to watch,” she said. “We played cards with them or did group therapy to keep them entertained.”

Authorities arrived on Thursday and evacuated the most critically ill patients. Boats came the next day to rescue the remaining staff and patients and take them to buses bound for the Louisiana State Hospital in Pineville.

“We learned a lot about working toward the common goal of survival,” she said. “Everyone was trying to help each other out.”

The week before Katrina arrived, Brian Stafford, M.D., the child psychiatry training director at Tulane, was not in New Orleans—he was working as scheduled in Lafayette, La. On Thursday of that week, he drove to Dallas with his wife, and after the hurricane hit, they went to Baton Rouge to work in the main shelter in the Pete Maravich Activity Center and the nearby field-house.

Stafford helped set up a small shelter for children separated from their parents by the chaos of the rescue process. To provide some stability, the designated children's area accepted only volunteers who committed to 12-hour shifts and were willing to return. Media access was limited to minimize disruption. The staff found teachers and day care workers among the evacuees who provided structure for the children by arranging meals, playtimes, and naps. They also worked with parents who needed help. By September 12, children were attending school in Baton Rouge, and family reunification appeared to be progressing well, said Stafford. All school-aged children are being followed through school-based clinics and linked to mental health care services in the Baton Rouge area, he said.

“New Orleans is more than just a city down the road,” said Mississippi native Grayson Norquist, M.D., M.S.P.H., who was visiting the city as the storm approached. “New Orleans serves as a cultural center for the entire region, so its loss is a blow for all of us.”

Along the Mississippi coast, hospitals and community mental health facilities were gone or damaged, patients evacuated, and staffs dispersed, said Norquist. The New Orleans Veterans Affairs hospital was closed and its director sent to work at the VA in Jackson, Miss. Private patients reported that they could not find their doctors, and physicians did not know where their patients were.

Before the storm hit, Norquist and his wife returned to Jackson, where he had begun work eight months earlier as chair of psychiatry at the University of Mississippi Medical School after 14 years at the National Institute of Mental Health. For the first time ever, all area mental health and substance abuse agencies met together and agreed to coordinate their services for the 2,000 evacuees in the Jackson Coliseum.

“Our attitude was that these are our people, and we're going to take care of them,” recalled Norquist. “We'll worry about who's going to pay for it later.”

As in Lafayette, La., local practitioners organized the response to the influx. There appeared to be no central agency coordinating the medical relief effort. “It's not clear how the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services funneled medical volunteers,” he said.

Robert Dahmes, M.D., found himself a refugee in his own country, legally cut off from his livelihood when he crossed a state line. Dahmes was born and raised in New Orleans and maintained a private practice and worked on clinical drug trials there. The storm dispersed his patients, and his research records were lost. He spent three weeks in Sparta, Ga., at his sister-in-law's house, trying to get medical authorities in Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama to respond to his licensing requests.

Out-of-state volunteer physicians working in disaster zones were given temporary licensure to work there. But nonreciprocal state-by-state licensing requirements created an unexpected burden for doctors evacuated after Katrina. No one had foreseen the displacement of an entire city for months or years, leading to its citizens' having to seek jobs in other jurisdictions.

In the end, Dahmes decided to return home to clean up his house and try to restart his practice. The state's office of emergency preparedness said it would hire him to provide counseling for storm victims once his office is in working shape again.

Britta Ostermeyer, M.D., expected evacuees from New Orleans to come to Houston, but had no idea there would be so many. Doctors, counselors, and other personnel from area hospitals and the Red Cross set up medical facilities in four hours in the arena next to the Houston Astrodome. They partitioned off 10 examining rooms and used a table inside the dome as a screening station. Hospitals donated drugs to create an instant pharmacy.

As they met with patients, psychiatrists and counselors listened to stories of survival laced with fear of dying, of watching others die, and of not knowing whether their neighbors had been rescued, said Ostermeyer, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Baylor University School of Medicine and director of the Ben Taub Hospital psychiatry outpatient program. Many had symptoms of depression, anxiety, and acute stress reactions. Fewer than a dozen, most with previously identified mental illness, needed to be hospitalized.

“Most patients showed enormous gratitude for getting to Houston and finding shelter and necessities like clothing and shoes,” she said. The clinic in the arena closed on September 18, as patients were absorbed into mental health units of the Harris County Hospital District.

Britta Ostermeyer, M.D., stands before a makeshift examining room at the Houston Astrodome. “Most patients showed enormous gratitude for getting to Houston and finding shelter and necessities like clothing and shoes.”

Photo courtesy of Britta Ostermeyer, M.D.

“We always said this would happen someday, that the city would be under water,” recalled New Orleans native Joni Orazio, M.D. After the storm, up to 13 relatives camped out at her house in Lafayette, along with her immediate family. After tending to her patients each day, Orazio volunteered to work at the Cajun Dome, the sports arena for the University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

Two nephrologists from the Lafayette Parish Medical Society organized a makeshift clinic at the dome. Orazio started on the medical side, then switched to a separate part of the clinic for mental health services. She worked side by side with local psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and health administrators who staffed the clinic from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. Doctors emptied their stores of drug samples. A pharmaceutical rep dropped off more medications.

Doctors thumbed through the Physicians' Desk Reference, trying to figure out just which “little white pill” an elderly evacuee was taking for her high blood pressure. They wrote 30-day prescriptions for patients to get them through the first phase of the emergency but tried to avoid any Schedule II drugs.

Orazio could issue emergency certificates for commitment to open beds in local hospitals, if needed.

“It's not easy to talk to a scared delusional person with the cops standing there, but we were lucky to have the hospital nearby,” she said.

After a week of this, she said, “I found out I wasn't Superwoman.” ▪