Storms' MH Crisis Grows As Hurricane Season Nears

Aaron Levin

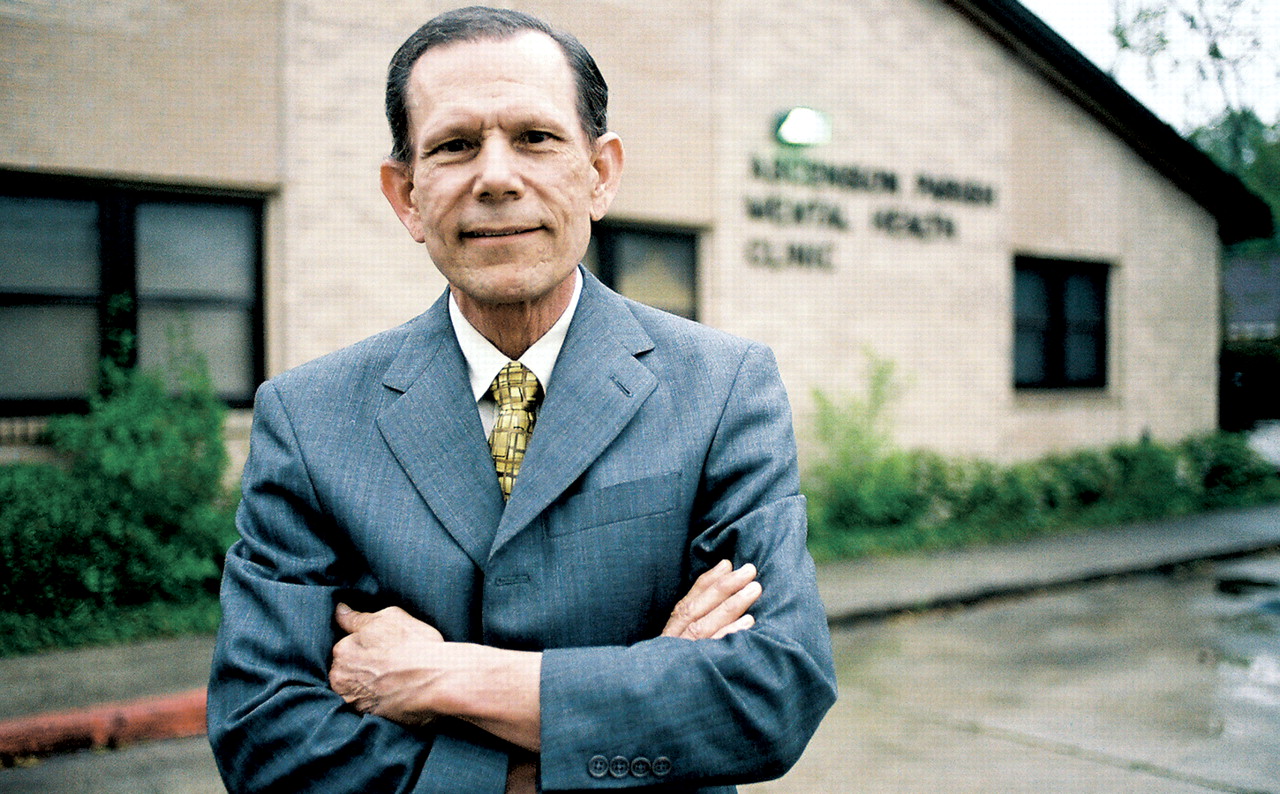

Donald A. Schexnayder, M.D., Ph.D., fled from New Orleans briefly before Hurricane Katrina hit, then returned to help evacuees in the Lamar Exhibition Center and continue his regular work at the Ascension Parish Counseling and Substance Abuse Center in Gonzales, La. (shown in background). With his house in New Orleans destroyed, he decided to move to Baton Rouge.

The days are over when volunteer psychiatrists were dropping into hurricane-battered Louisiana like smoke jumpers on a forest fire.

“We're in grind-it-out mode now,” said David Post, M.D.“ There's no adrenaline rush anymore.”

In the states hit by hurricanes Katrina and Rita last fall, grinding it out in the mental health arena means not only finding and treating people, but also dealing with recovery money, government bureaucracy, and thoughts of an impending hurricane season starting on June 1.

Physical damage in the region is still widespread. Driving along coastal roads in Mississippi reveals miles of house foundations, and the devastation of wind and storm surge can be seen well inland too. In New Orleans, besides the houses destroyed by flooding, many others were ruined from lack of electricity to run air conditioning or refrigerators while owners were evacuated not for days as they had planned, but for weeks. As of mid-March, traffic lights in much of the city were still not operating. Farther west, places such as Lake Charles, La., and Beaumont, Tex., suffered heavy damage from Hurricane Rita.

The dislocation of hundreds of thousands of evacuees is still straining human services in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi in areas away from the path of the storms' devastation.

Psychiatrists along the Mississippi coast report an increase in cases of depression, substance abuse, and relational problems, especially among people sharing accommodations with relatives or among formerly separated couples thrown together again by the need for housing with their children, said Elizabeth Henderson, M.D., president of the Mississippi Psychiatric Association.

“Life in FEMA trailers is dreary and bleak,” she said.“ I'm concerned with what will happen to children this summer when school is out unless recreational programs are in place.”

She has not heard much about increased PTSD symptoms, but like psychiatrists elsewhere in the region, she fears that even a minor tropical storm this summer will trigger symptoms among people who have not yet recovered from Katrina or Rita.

In Gulfport, Miss., at the Gulf Coast Mental Health Center, plastic sheets still covered holes in the center's ceiling, and the floors were carpetless seven months after the storms. The center is seeing fewer Medicaid patients and more middle-class ones, said director Jeffrey Bennett, L.C.S.W. Many severely mentally ill individuals are now in northern Mississippi, Alabama, or even Illinois. Staff members have been living in trailers because their own homes were damaged.

“Now there are no psychiatric inpatient beds in New Orleans. People wait in emergency rooms two or three days for a placement.”

“There's a mass grieving process going on,” said Bennett's colleague, psychologist Steve Barrilleaux, Ph.D. “You lose your bearings around here. People say, `I'll never be able to show my kids the beach the way it was.' You can't drive through it without tearing up.”

In New Orleans, Dudley Stewart, M.D., is seeing more patients with adjustment disorders, subthreshold PTSD, difficulty concentrating, or irritability, no matter what they had before.

“Some people are immobilized, some are resilient,” said Stewart, the APA Assembly representative to the Louisiana Psychiatric Medical Association. Some are looking for the quick fixes provided by alcohol or drugs, he added.

“You can see the impact on the elderly just by looking in the obituary columns,” said Howard Osofsky, M.D., chair of psychiatry at LSU Health Sciences Center in New Orleans. “People who had managed because they had children, relatives, and neighbors to support them were lost without them. The destruction of so many parts of the city means that the sense of community and the part of one's identity that it represents is lost.”

Physicians, too, were not immune from the storms' effects, and some have left the area after offices were destroyed and patients were evacuated.“ We're going through our own recovery process,” said Stewart.

The number of practicing psychiatrists in Orleans Parish has dropped from 196 to 22, according to the New Orleans Times-Picaynue. Much, but not all, of that difference is traceable to exodus of medical personnel from Tulane and Louisiana State University, but other psychiatrists have relocated to other cities too, said Stewart.

Psychiatrists are not alone. Only 140 primary care doctors now practice in the city, compared with 617 before Katrina. There are just 77 working dentists today, down from the 259 before the storm. Ironically, the loss of doctors means New Orleans is eligible to be named a federal Health Professional Shortage Area, allowing physicians to charge 10 percent more for Medicare treatment and triggering incentives (like medical school loan forgiveness) to attract new doctors to the area.

Some medical residents have departed because Katrina wiped away their training opportunities along with hospitals and houses, said Martin Drell, M.D., clinical director of the New Orleans Adolescent Hospital (which is still waiting for state approval to reopen). Psychiatric residents at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center were shifted to the Oschner Clinic, but 30 percent of the medical faculty had to be furloughed, and flooded offices won't be usable before March of next year, said Osofsky.

Donald Schexnayder, M.D., Ph.D., used to live in New Orleans and commute north to the Ascension Parish Counseling and Substance Abuse Center in Gonzales, where he is the medical director. After his home near Tulane University was wrecked, he moved permanently to Baton Rouge and now commutes south to work.

In Lake Charles, La., hard hit by Hurricane Rita, Dewey Archer Jr., M.D., reports that his patient census at the Institute for Neuropsychiatry has nearly rebounded to pre-storm levels, although the population mix has changed. Today, he's seeing more adults yet fewer geriatric or child patients compared with before the storm.

Throughout the region, treatment is complicated by structural weaknesses in existing mental health systems, shifts in funding patterns, and bureaucratic intrusions from every level of government, according to several sources.

“The public mental health system in Louisiana was underfunded and overburdened even before Katrina,” said Kathleen Crapanzano, M.D., medical director of Louisiana's Office of Mental Health. “Now there are no psychiatric inpatient beds in New Orleans. People wait in emergency rooms two or three days for a placement in a private setting or a state hospital.”

Texas's mental health system had been paring services and closing mental hospitals in the two years before the storms. Then the evacuees began arriving by the thousands. “FEMA funding is now drying up, but nothing has changed in the previous state underfunding of mental health services,” said George Santos, M.D., of Houston's West Oaks Hospital.

Federal emergency funding fills part of the gap in helping evacuees, but that raises other questions. Arguments have already begun in Louisiana about who gets what. Health officials outside New Orleans point to relocated evacuees in their districts and want increased funding based on the new population served. But that means taking money from already underserved New Orleans and from rural areas in the northern part of the state. “It's robbing Peter to pay Paul,” said Crapanzano.

Beyond the money issues, said Post, who is medical director of the Capital Area Human Services District in Baton Rouge, “everything is getting more bureaucratic and political.” He organized field teams under the federal Stafford Act to go on site to shelters and trailer villages to identify people who needed treatment. Once the emergency phase was over, FEMA worried about information collected on patients, told him to stop, and impounded his records, said Post. He is now awaiting clarification from federal and Louisiana authorities. In fact, much disaster relief is intended for a shorter-term response rather than the years it will take to recover from last year's storms.

“We need to look at the Stafford Act,” he said. “It was set up for crisis management, not for field triage and referral. Now you can't just be good old Dr. Post, treating people. The new bureaucracy is definitely affecting the treatment of patients.”

What happens next to the people still struggling with the aftermath of Katrina and Rita was on the mind of every psychiatrist interviewed for this article.

“Another hurricane will make last year look like a rehearsal for a disaster,” said Susan Sparkman, M.D., past president of the Texas Society of Psychiatric Physicians.

“Among the mental health staff, the next hurricane season is a ticking clock,” said Crapanzano. All disaster preparation before Katrina planned for a five-day evacuation. Southeast (Louisiana) Hospital evacuated for 33 days, she said. Now the state says it will evacuate in the face of a category 1 or 2 storm (Katrina was a category 4) and make evacuation decisions 72 hours in advance of the storm. But at that time, a hurricane's projected landfall is so uncertain that there will inevitably be a lot of false alarms, which may cause many to reexperience last year's events. Staffers also have to balance their responsibilities to patients with their own families' safety. Last year, hospital workers on duty evacuated with patients but were never relieved by other shifts.

Planning by governments and medical groups in all three states for future disasters is ongoing, but much remains incomplete or uncoordinated.

“We need a system in place that can be quickly and effectively mobilized,” said Sparkman. Organizing a chain of command and uniting disparate and often competing professional specialties won't be finished before new hurricanes arrive this summer.

“The need is there and definitely not being met,” added Henderson. “I have no idea how to meet it except in collaboration with other licensed professionals. This is going to be with us for a long, long time.” ▪