Better Monitoring Urged for Youth Taking Newer Antipsychotics

A series of recent reports documenting increases of between 200 percent and 300 percent in the prescribing of second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) to children and adolescents since the mid-1990s has prompted experts to remind prescribers that a critical part of using the medications involves clinical monitoring and follow-up of the drugs' potentially serious acute and long-term adverse effects.

“Prescribing of antipsychotic medications to children and adolescents is certainly a serious step for any clinician to undertake,” noted Christoph Correll, M.D., director of the Adverse Events Assessment and Prevention Unit at Zucker Hillside Hospital/Long Island Jewish Medical Center and an assistant professor of psychiatry at Albert Einstein College of Medicine. “We really have to strike a balance between the efficacy of these medications and the severity of the conditions for which they are being prescribed, versus the potential for serious side effects.”

No SGAs are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in children and adolescents. The only antipsychotic medications with approved pediatric indications are haloperidol (for Tourette disorder, treatment-resistant severe behavioral disorders, and treatment-resistant hyperactivity with conduct disorders), pimozide (Tourette disorder), and thioridazine (for severe behavioral problems and hyperactivity with conduct disorder).

As a result, child and adolescent psychiatrists, pediatricians, and family practice physicians are left with limited options for treating youth with various disorders who come into their practices with often significantly impairing constellations of symptoms. With no approved pediatric indications and only minimal data regarding either efficacy or safety of the newer medications in pediatric patients, off-label prescribing of SGAs has been significantly increasing since the mid- to late-1990s.

Over the last two years, at least six major studies have been published in peer-reviewed journals not only detailing the large increases in prescribing rates, but also beginning to shed light on prescribing trends such as what types of practitioners are prescribing which medications, to which patients, and for what disorders.

Importantly, researchers now agree, evidence is building that establishes efficacy and safety profiles for SGA use in younger patients. But evidence is also mounting that monitoring for SGA-associated weight gain (and corresponding metabolic abnormalities), neuromotor abnormalities, extrapyramidal side effects, and sedation may be even more important in younger patients than in adults taking the drugs. Children, it seems, may be significantly more sensitive to and likely to develop acute treatment-emergent adverse effects when prescribed SGAs.

Most Prescribed to Outpatients

“There has been a substantial increase in the prescription of antipsychotic medications to young people in office-based practice,” said Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. Olfson and his colleagues reported in the June Archives of General Psychiatry results of an analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys (NAMCS) from 1993 to 2002. In 1993, the estimated number of office-based visits by patients 20 years and younger that included antipsychotic prescriptions was approximately 201,000. By 2002, the number had risen to an estimated 1,224,000.

Between 2000 and 2002, Olfson and his colleagues reported, about 1 in 10 visits (9.3 percent) by children and adolescents to a mental health clinician included an antipsychotic prescription, while a visit with a psychiatrist was twice as likely to result in an antipsychotic prescription (18.2 percent).

The number of office visits that included antipsychotic prescriptions was higher for males (1,913 visits per 100,000 population) than females (739 per 100,000) and for white, non-Hispanic youth (1,515 per 100,000) than for other racial/ethnic groups (426 per 100,000).

Overall, 92.3 percent of visits that included a prescription for an antipsychotic medication involved SGAs. The most common diagnoses associated with visits in which SGAs were prescribed were disruptive behavior disorders such as ADHD, oppositional defiant and conduct disorders (37.8 percent), mood disorders (31.8 percent), pervasive developmental disorders or mental retardation (17.3 percent), and psychotic disorders (14.2 percent).

Studies Identify Trend

The Olfson team's findings mirror those of other recently published studies. Another group, led by pediatrician William Cooper, M.D., at vanderbilt University, also studied the NAMCS database along with data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which includes information on visits to emergency departments and hospital outpatient clinics.

Cooper's group looked at data from the 1995 through 2002 surveys, finding that 5.7 million medical visits over that period included an antipsychotic prescription. Nearly 80 percent of those were written during office visits, and surprisingly, 32 percent of antipsychotic prescriptions reviewed by Cooper and his colleagues were written by specialists in areas other than mental health, such as family practitioners, pediatricians, and emergency physicians.

Again, white males were more likely to be prescribed an antipsychotic, and the most frequently listed diagnosis was ADHD or conduct disorder (29 percent) followed by bipolar disorder or depression (23.5 percent). Cooper documented a nearly sixfold increase in antipsychotic prescriptions from prescribers in a specialty mental health setting (for example, mental health clinics as well as psychiatric offices) compared with a threefold increase during visits to non-mental-health prescribers.

Other studies have recently found similar trends in Medicaid populations in Texas, Tennessee, and “Midwestern,” “Southern,” and“ Western” Medicaid pediatric populations.

“My sense is that we're seeing this increase in part because the newer, second-generation antipsychotics have fewer short-term neurological side effects [at least in adults] and so tend to have greater tolerability,” Olfson told Psychiatric News. “But we're in a situation now where I think the practice has gotten ahead of the research. We need to learn more about what kinds of disorders in the pediatric population these medications are efficacious in, and, at the same time, we need to learn more about safety, in particular with the metabolic risks that these medications pose.”

With Benefit Comes Risk

With these numerous reports of large increases in the number of SGAs prescirbed to youngsters have come questions of whether the increasing level of off-label prescribing is appropriate.

“I think we have to bear in mind,” Correll told Psychiatric News, “that in child and adolescent psychiatry, diagnoses are often moving targets. However, [the children who are prescribed antipsychotic medications, in general] have very concerning, distressing, and often significantly impairing symptoms that result in severe distress and functional impairment. It's not a case of parents simply saying `O.K, we just aren't happy with our kid, so do something.' “

Children and adolescents, Correll noted, often do not meet adult criteria for psychotic or bipolar diagnoses—the two primary approved indications for these medications in adults. In particular, he said, because of widely differing developmental stages of their brains, children often don't meet the time criterion for psychosis or mania, yet they are as impaired as adults who meet the criterion.

“So we use medications that have quite a few side effects—some very serious side effects—and those side-effects may actually be accelerated by growth and development,” Correll said. Children often initially gain a proportionately larger amount of weight on average than adults do while taking SGAs, he noted. However, the weight gain tends to plateau sooner.

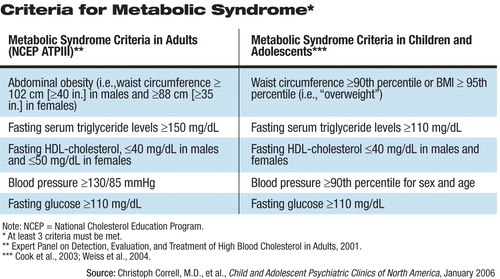

In addition, there is evidence to indicate that children and adolescents may be at higher risk for the development of metabolic syndrome while taking SGAs, and clinicians need to be vigilant for symptoms (see table above).

“The other concern is that it seems that whatever happens metabolically during childhood and adolescence may stay with them,” Correll added, “and then they cannot loose the excess weight in adulthood, and then the potential for cardiovascular disease and diabetes may be accelerated as well.”

Children and adolescents taking SGAs also may be more at risk than adults for some neuromotor abnormalities, such as tardive dyskinesia. However, while abnormal movements may occur at higher rates than in adults, Correll added, they seem to disappear more readily in children when the offending medication is stopped. Younger patients may also be more at risk of developing a discontinuation dyskinesia and more prone to the sedating effects of certain SGAs, Correll said,

However, he observed, overall the SGAs are thought to be safer in most respects than the older first-generation medications, and, importantly, they seem to have broader efficacy as well, “so that when you prescribe them, you are able to cover more bases—not just psychosis, but also basic mood instability, as well as depression, aggression, and impulsivity. Giving one medication that may cover many symptoms may be superior to giving multiple medications at the same time.”

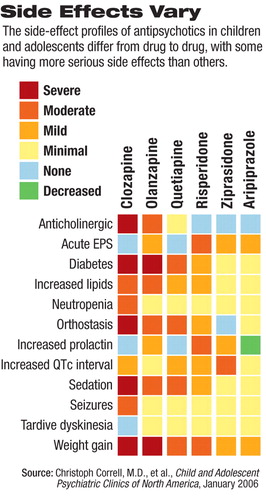

It is important to emphasize, Correll noted, that “although the different SGAs are named as a class, they are very heterogeneous drugs. We have to get away from speaking about them as all the same `class' when there are clearly some that are associated with more severe side effects—such as metabolic derangement—and some that have much less risk.”

Olfson and Correll agreed that until more data are available, clinicians must make the most informed prescribing decision possible, and above all, closely monitor children and adolescents taking SGAs.

Correll and his colleagues recently published proposed monitoring guidelines for children and adolescents who are being prescribed SGAs.

In addition, those researchers are completing data acquisition in a study of nearly 500 patients aged 5 to 19 taking SGAs. “We will soon be publishing articles on short-term and long-term follow-up data, up to three years,” Correll said.

The study is following nearly 300 antipsychotic-naïve patients out of the 500 and is “beginning to provide a look at differential trajectories.” ▪