Patient Charged With Murder Of Schizophrenia Expert

It is a rare scenario, the potential nightmare in the life of a psychiatrist: a patient becomes violent, even homicidal, while the psychiatrist and the patient are alone in the psychiatrist's office.

Wayne Fenton, M.D., often made remarks to this effect: “All anyone has to do is walk through any downtown area to appreciate that the lack of adequate treatment for patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses is a serious problem in this country. We wouldn't let our 80-year-old mother with Alzheimer's live on a [sewer] grate. Why is it all right for a 30-year-old daughter with schizophrenia?”

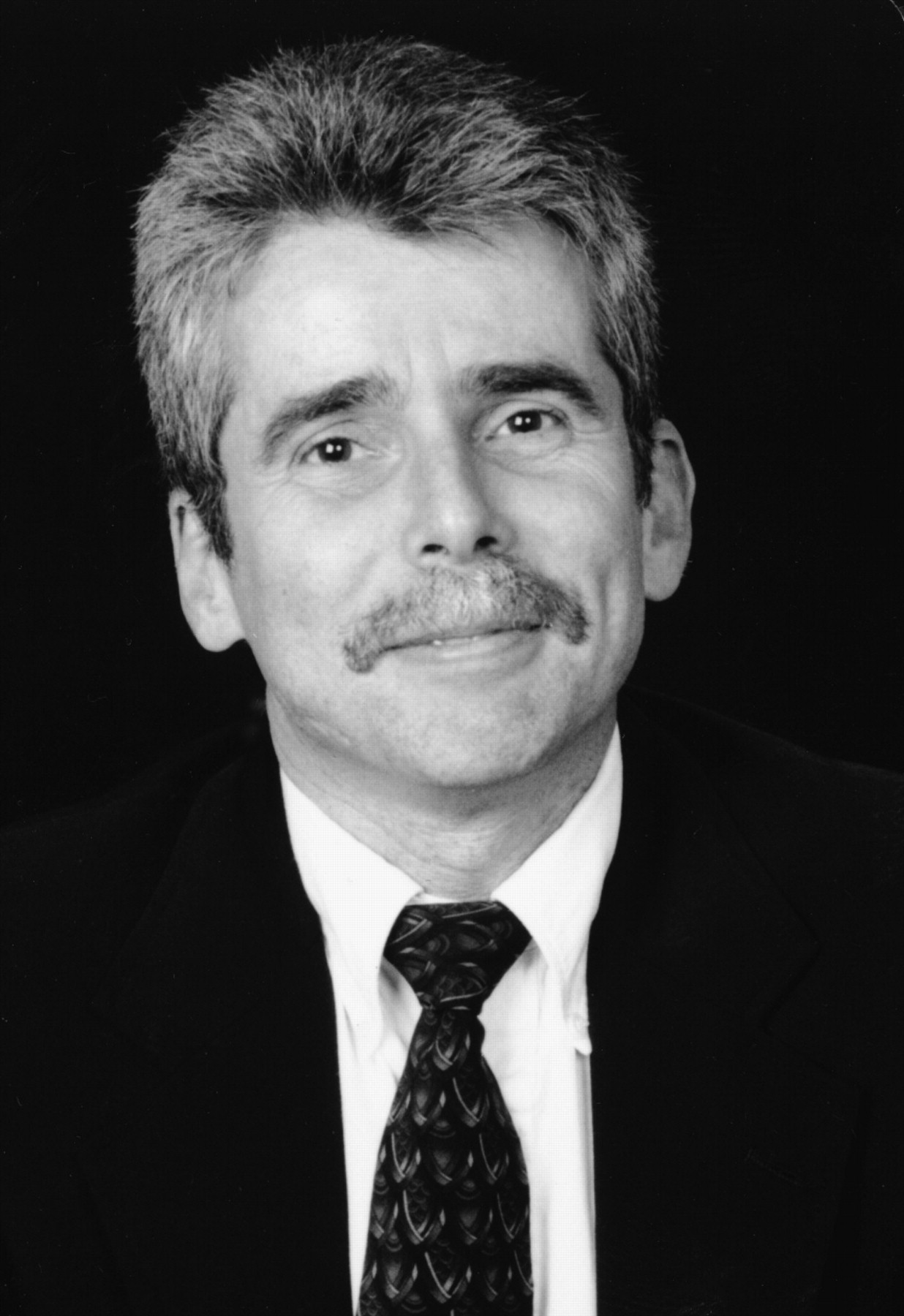

Photo Courtesy of NIMH

When Wayne Fenton, M.D., an administrator at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and renowned expert in the diagnosis and treatment of schizophrenia, was asked by a colleague to see a patient in crisis—who was reportedly suffering ongoing paranoid and complex delusions but was now also noncompliant—Fenton agreed. After all, Fenton was used to referrals of challenging patients.

Even though it was Labor Day weekend, Fenton, director of the Division of Adult Translational Research and associate director for clinical affairs at NIMH, met with the 19-year-old patient and his father on Saturday, then made an appointment for follow-up the next week. However, on Sunday, according to court documents, the patient's father called Fenton, pleading with him to see his son again. The patient reportedly was very agitated. He was unhappy with his medications and was refusing to take them, the father told Fenton.

Holiday weekend or not, however, Fenton was known for his devotion to patients—especially those who were severely ill. This patient was clearly seriously ill and needed help.

Fenton agreed to see the patient and his father at his private office again at 4 p.m. that Sunday afternoon, telling the father he would try to convince the patient to continue his medication or switch to an injectable, long-acting formulation.

Late on that Sunday afternoon, something went terribly wrong. The patient's father brought his son to Fenton's office, then apparently left to do an errand while his son talked with Fenton. It is unclear whether Fenton thought the father would stay during the appointment.

According to Montgomery County, Md., police reports, when the father returned, he found his son wandering outside the office building with blood on his hands and clothing. The father called 911 and tried to enter Fenton's office suite, only to find the door locked.

When paramedics arrived, they found Fenton lying on his office floor, unresponsive and severely beaten. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

The patient gave differing accounts to police. He allegedly told police shortly after the murder that he had killed Fenton in self-defense. He was afraid that Fenton was about to sexually assault him. The patient also said that his father had murdered Fenton.

The patient, who remains in custody, was charged with first-degree murder. After pleading “not criminally responsible” due to mental illness on September 18, he was awaiting transfer to a state psychiatric hospital where he will be evaluated to determine competency to stand trial.

Rare but Present Danger

Wayne Fenton died while trying to help a seriously ill patient. Numerous colleagues contacted by Psychiatric News expressed profound shock at Fenton's death, yet many were not completely surprised, given the circumstances.

Steven Sharfstein, M.D., immediate past president of APA and president and CEO of Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore, said, “Violence like this against psychiatrists is very rare, but the current situation reminds all of us to remain cautious. We must reassess safety with each and every patient we see. Often though, even when we do our best to reduce risk, unexpected `worst-case' scenarios occur.”

APA President Pedro Ruiz, M.D., observed, “We should not overreact and think that most patients with mental illness are more dangerous than the population at large. To do so would negate the work of Dr. Fenton. To build stereotypes would undoubtedly lead to stigma, thus increasing barriers to providing patients with the highest quality of care possible. Having said that, it is absolutely appropriate and necessary for psychiatrists to be cautious and fully alert in detecting signs of aggression and dangerousness when working with severely ill patients.”

Indeed, psychiatrists and mental health professionals are subject to a significantly higher risk of violent crime than most other categories of professionals. The U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), and the Department of Justice (DoJ) agree that health care workers face some of the highest levels of job-related violence. BLS statistics show that there were 69 homicides of health care personnel from 1996 through 2000.

According to the DoJ's National Crime Victimization Survey for 1993 to 1999, the annual rate for nonfatal violent crime for all occupations was 12.6 per 1,000 workers. For physicians, the rate was 16.2, and for nurses it was 21.9. But for psychiatrists and mental health professionals, the rate was 68.2, and for mental health custodial workers, 69.

Some Risk Factors Identified

Much has been written about the assessment of patients to determine risk of violence. Many psychiatrists have been quoted as stating that most mentally ill patients are not violent. and while the most reliable predictors of violence are history of violent acts and untreated mental illness, until recently few credible statistics were available on the prevalence of violence among mentally ill people.

A recent notable exception is the NIMH CATIE (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness) study. That study involved extensive screening and diagnostic examinations of all patients who entered the protocol. Researchers assessed 1,410 patients with schizophrenia and interviewed them about violent behavior in the six months prior to the start of the study.

The CATIE investigators found that 19.1 percent of patients had exhibited some type of violence over the previous six months. However, only 3.6 percent of the patients reported any serious violent behavior over the prior six months.

CATIE investigators used the MacArthur Community Violence Interview, which defines minor violence as “corresponding to simple assault without injury or weapon use.” Serious violence is defined as“ corresponding to any assault using a lethal weapon or resulting in injury, any threat with a lethal weapon in hand, or any sexual assault.”

Importantly, the CATIE study documented “distinct, but overlapping, sets of risk factors” associated with minor and serious violence (Psychiatric News, July 7). Positive symptoms, especially thoughts of persecution, significantly increased the risk of both minor and serious violence, while negative symptoms, such as social withdrawal, appeared to reduce risk. The CATIE results have added weight to the long-standing recommendation that risk assessment must be undertaken with every patient, and reassessment must occur periodically if clinicians are to safeguard themselves effectively (Original article: see box).

Options Are Few

Many of those who spoke with Psychiatric News about Fenton's death echoed the same frustration: When a patient is assessed and deemed to be at significant risk of serious violence or, worse yet, when the patient has already exhibited violence, clinicians often find themselves with limited options on how to handle the patient.

The circumstances surrounding Fenton's death “speaks volumes about the extent to which the mental health system has unraveled,” said Mary Zdanowicz, executive director of the Treatment Advocacy Center. “There really is no system left to respond when a person is having a psychiatric crisis.”

Zdanowicz said that the mental health community's focus on recovery—the “brighter side of mental illness” that has gotten so much attention recently—“is a great thing. But that focus on happier outcomes has been done at the expense of acknowledging the other side” of the outcome continuum, which includes those patients who are slow to or never recover.

Following the wave of closures of state mental hospitals that left many severely ill patients on the streets, 42 states enacted some type of law concerning mandatory or assisted outpatient treatment. All states have involuntary commitment statutes.

Maryland, the state in which Fenton was murdered, has no assisted outpatient treatment law. However, it is unclear whether mandated or assisted treatment would have been a beneficial or appropriate option for the patient charged with Fenton's murder. Moreover, it is not known whether the patient's family had sought involuntary commitment. The patient, according to his family, had no history of violence, either to himself or to others; it is not clear whether he had been hospitalized in the past. Yet at the time he saw Fenton, according to family and police documents, the patient had been ill for at least six months, had seen several psychiatrists, and was recently refusing treatment as his illness grew progressively worse.

“Decades ago, it might have been true that the majority of violent patients would have been treated as inpatients,” said Carl Bell, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and public health at the University of Illinois at Chicago and president and CEO of the Community Mental Health Council.“ But today, you have to deal with them in the outpatient setting.

“Hindsight is, of course, 20-20,” Bell continued.“ Depending on the existing infrastructure of psychiatric emergency services in the area, a psychiatric emergency room is probably where this kind of patient should have been seen, not in a private office.”

Bell stressed that he was speaking in general and had not evaluated the patient charged with Fenton's murder.

It may have been the lack of inpatient treatment options that led Fenton to see the patient in Fenton's private office, colleagues said. Several sources interviewed for this article observed that psychiatrists are often reluctant to send patients to an ER because they'll sit there for hours and eventually be released because the ER doctors are faced with the same limitations—a lack of psychiatric hospital beds—as are psychiatrists providing outpatient care.

Fenton's death, Bell said, “clearly calls out for a careful examination of what the psychiatric emergency services infrastructure is in various places. You end up getting inappropriate referrals in inappropriate settings” when services are limited or simply not available.

“It's so troubling to me,” said Zdanowicz, “that the knee-jerk reaction to this tragedy will be for people to say, `Most people with mental illness are not dangerous.' But the fact of the matter is, some are.” ▪