ACGME Work-Hour Rules Challenge Old Assumptions

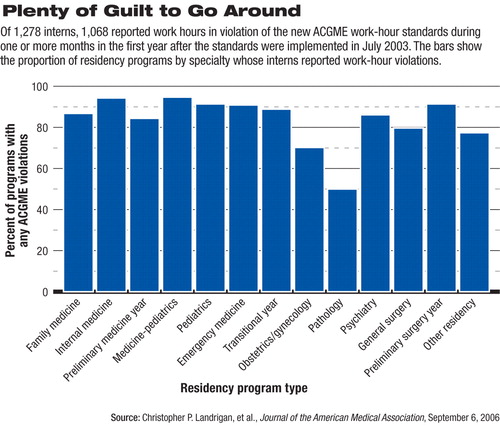

Violations of resident work-hour rules issued by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) three years ago were pervasive across programs and specialties a year after the rules' implementation. That was the bottom-line finding of a study reported in the September 6 Journal of the American Medical Association.

Psychiatry was not exempt, though the survey of first-year residents did not break out whether the violations reported by psychiatry residents occurred while on psychiatry services or during the six months that PGY-1 residents spend on medicine and neurology services. The lead author of the JAMA report, echoing most educators who spoke with Psychiatric News, said the violations reported by psychiatry residents may well have occurred during the months on medicine or neurology rotations (see chart).

“[A]s we move toward testing competencies, I think we will find that hours in the hospital don't correlate with what we actually care about.”

“In a similar vein, although most emergency programs don't schedule residents to work more than 12 hours, we saw many 30-hour violations in ER residents, probably from times they were rotating on medicine and surgical services,” Christopher Landrigan, M.D., director of sleep medicine and patient safety at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston, told Psychiatric News.

Though it is not possible to determine when the violations reported by psychiatry residents occurred, educators in psychiatry reported that for the most part the issue of resident work hours has not been the difficult one it has been for other specialties.

Robert Krasner, M.D., president of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT), said that in the psychiatry program at Northwestern University School of Medicine, he believes the ACGME work-hour rules have had little or no impact on training.

“From what I know anecdotally, the same has been true in other programs,” he said. “It's as if no one has skipped a beat.”

He said the shorter length of inpatient rotations, greater emphasis on outpatient work in clinics that open and close at regular business hours, and less frequent on-call duty have traditionally made for a friendlier residency experience in psychiatry.

Lea DeFrancisci, M.D., chair of APA's Committee of Residents and Fellows, said she believes the new rules have largely worked well to protect trainees and that psychiatry programs have not had a difficult time complying.“ There is a reason why psychiatry has typically attracted more women—because the residency is friendlier to people with families.”

She is a fourth-year resident at New York University School of Medicine and a fellow in child psychiatry. New York has had a longer experience with strict duty-hour regulations than other states as a result of the Libby Zion case. Zion was a patient in New York who died in 1984 allegedly because of errors made by overworked residents.

The ACGME work-hour rules were modeled largely on those put forward by the Bell Commission in New York state in the wake of the Zion case (see box).

Balancing Patient Care, Quality Education

Still, the imposition of duty-hour regulations—violations of which can be met with steep fines in some cases and/or the threat of loss of accreditation—has added to the work burden of directors and training coordinators who must balance the demands of patient care while providing a high-quality educational experience for trainees. For training directors in psychiatry, it may amount simply to another layer of paperwork or computer programming.

“We are obliged to find a way of effectively monitoring duty hours and ensuring that residents record their time,” said Christopher Varley, M.D., director of child psychiatry training at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

He said the school has adopted a computer program known as Verinform by which trainees can track their hours. He believes that it may have to be shown only once that the training program is in compliance with rules; after that, the obligation to monitor hours may be dropped.

But many programs in specialties other than psychiatry have had to make substantial adjustments to ensure that service times are covered while also meeting the duty-hour rules. Some programs, including some in psychiatry, have adopted “night float” rotations to meet the prohibition against working more than 30 hours; residents may work several nights in a row but leave early the next day, rather than working around the clock.

DeFrancisci said that can mean the resident misses classes the following day, but she believes that having well-rested trainees is more important.

“If you are not tired, you learn better anyway,” she said.“ Overall you miss some class, but it leaves the residents who are there better off. It's not perfect—it's flawed either way—but it's better than it was before.”

Training Residents to Say `I Have to Go'

“Flawed either way” appears to be an apt description of the increasingly difficult task faced by academic medical centers that must provide adequate continuity of care for hospital patients who are sicker and have more complex chronic conditions, at a time when public funding of graduate medical education through the Medicare program has been cut substantially.

And the duty-hour rules appear to have heightened the dilemma of how to meet every obligation with fewer resources. Some training directors in specialties other than psychiatry have said that duty-hour restrictions pit conformity with the law against adequate patient care and the teaching of professionalism.

As one neurology training director, Wendy Peltier, M.D., of the Medical College of Wisconsin, put it: “We are training residents to say, `When my time is up, I have to go.' I really worry about that because what has made me a good clinician is the habit of responsibility to the patient that I learned as a resident.

“Teachers my age or older trained in an era when the hospital was run in a different way. Now the residents have to monitor their time so closely that it has accelerated the pace of teaching even more than the diminishment in hospital stay for patients has. We sometimes base our entire teaching around making sure the resident can clock out on time.”

The general sentiment is echoed by some in psychiatry. Sidney Weissman, M.D., a long-time training director and past president of AADPRT, told Psychiatric News that he knows from experience that there are violations of duty-hour rules in psychiatry. And the obligation to monitor those violations can cause subtle and not-so-subtle shifts in emphasis on the part of educational programs.

“Part of being an intern and resident is learning responsibility to the patient,” he said. “If you have an environment focused on responding to rules, then you are not focusing on learning. I don't want someone thinking about whether they need to go home in 15 minutes. I want someone who is thinking about why this patient is in trouble and what we need to do.”

The issue of continuity of care is especially acute in the“ hand-off” of patients from one physician who is clocking out to another who is coming on. The “hand-off”—where vital information is transferred—has become a focus of interest as a point in the system of medical care rife with potential for error.

“There are degradations in the quality of information the more hand-offs there are,” Weissman said. “One of the things the rules have done is created a situation where there are more hand-offs, and hospitals have had to reorganize how they deliver care.”

DeFrancisci agreed. “When I was doing night float rotations in medicine, you never knew what happened to patients you saw the night before,” she said. “They get transferred to a day team, and that was the last you saw of them. Certainly, continuity of care is potentially sacrificed.”

Landrigan, author of the JAMA report on work-hour violations, believes the concern about continuity may be misplaced.

“It would certainly not be reasonable to advocate for residents to clock out the moment their replacement arrives, if an acute-care situation exists that requires their continued presence,” he told Psychiatric News. “On the other hand, the routine violation of limits that is currently taking place is entirely preventable, with a somewhat more rational scheduling system.

“For example, if the absolute limit for consecutive work has been set at 30 hours, why is it that residents are routinely scheduled to work right up until this limit?” he wondered. “Wouldn't it be more prudent to routinely schedule them to go home at the 28th hour, so that there is a cushion of time for them to sign out appropriately and deal with the predictable crises that arise in medicine?”

Landrigan also believes that the duty-hour limits set by ACGME—largely in an effort to forestall regulation by Congress—are far in excess of what the airline and other industries require for safety and what is dictated by available evidence.

“What we have determined to be normal working hours is grossly at odds with what other industries practice,” Landrigan said. “The idea that devotion to patients requires 30 hours of continuous service is deeply contradicted by the evidence. We know that interns working more than 30 hours straight make more errors and that their empathy drops and their learning deteriorates.”

He acknowledges the dilemma in which training directors have been placed.“ This was an unfunded mandate,” he said. “Programs have been expected to comply without any resources or technical expertise to do so. The reality is that they simply don't have the bodies on site to do what they need to do.”

Ultimately, Landrigan believes the duty-hour rules are a flawed solution to the problem of patient safety and that the movement toward teaching“ competencies” backed up by evidence of learning is a step in the right direction.

“In the past we have thought of time in the hospital as a proxy for learning,” Landrigan said. “But as we move toward testing competencies, I think we will find that hours in the hospital don't correlate with what we actually care about.”

“Interns' Compliance With Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Work-Hour Limits” is posted at<http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/296/9/1063>.▪