Suicide Data Counter Claims Of Antidepressant Link

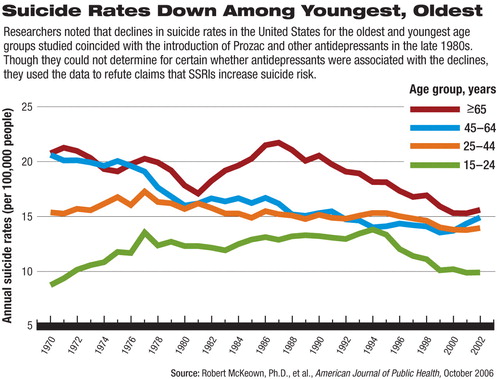

Suicide rates among teens and young adults have been on the decline since the mid-1990s. In addition, suicide rates among elderly Americans have been dropping since peaks in the late 1980s.

Researchers reporting their findings in the October Journal of Public Health said they don't have enough information to determine what may be leading to the lower rates for the youngest and oldest of four age groups studied, but they speculated on a number of possible factors including improved trauma care, an increase in healthy life expectancy, the advent of suicide-prevention and depression-screening programs, and an increase in prescriptions of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

In an interview with Psychiatric News, lead author Robert McKeown, Ph.D., called the study results “puzzling” because “almost any explanation one might put forth for the drop in suicide rates should affect the middle two age groups.”

McKeown, director of the University of South Carolina Division of Health Sciences Research Core and a professor of epidemiology at the Arnold School of Public Health, studied the numbers of suicide deaths abstracted from the Vital Statistics of the United States for each year from 1970 to 1990 and from the National Center for Health Statistics' annual mortality reports from 1991 through 2002.

He and his colleagues categorized the suicide deaths by age into four groups—15 to 24, 25 to 44, 45 to 64, and 65 and older.

They found that among the youngest age group, suicide rates peaked in 1994, at 13.8 suicide deaths per 100,000 people. Then the number of suicide deaths began a decline that lasted through the 1990s and early 2000s. In 2002, the last year for which McKeown collected data, there were 9.9 suicide deaths per 100,000 people.

Rates among the oldest age group fluctuated during the 1970s, declined until 1981, rose sharply to a peak in 1987 of 21.7 suicide deaths per 100,000, and declined to 15.3 deaths in 2001. “Suicide rates in this age group began to drop in 1988, which coincides with the introduction of Prozac,” he noted.

For those aged 45 to 64, suicide rates declined during the late 1970s but increased each year from 1999 to 2002, and rates among those aged 25 to 44 remained relatively stable through the 1980s and early 1990s, with a slight decrease after 1995 and stabilization reappearing from 1999 to 2002.

Part of his impetus for publishing the study, McKeown said, was to point out the paradox concerning claims that SSRIs may put young people at risk for suicide. Such claims don't jibe with the fact that suicide rates dropped during a time when the number of SSRI prescriptions began to increase, he noted.

“One would expect that with the increase in use of these medications, you would also see an increase in suicide. In fact, just the opposite has happened,” he said.

McKeown cited a 2003 study by Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., that found an inverse association between increasing use of SSRIs and decreasing adolescent suicide rates in an analysis of prescription drug data obtained from a large pharmacy benefit manager in Texas.

He cited additional studies showing rising prevalence of antidepressant treatment throughout the 1990s, when suicide rates were dropping for certain age groups.

“One of the things we need to look at more closely is whether there were differential prescribing patterns for different age groups,” McKeown said.

Improvements in trauma care during the past couple of decades also may have enabled physicians to save the lives of increasing numbers of people who made suicide attempts and would otherwise have died, he noted.

There may also be a cohort effect among people in the different age groups. For instance, the 45-to-64 age group whose suicide rate declined in the late 1970s may have “aged into” the oldest group, which subsequently experienced a drop in suicide rates in the late 1980s.

“The decline in suicide rates among the 15-to-24 year age group could reflect the impact of a new cohort of people who are at lower risk for suicide for reasons we don't yet fully understand,” McKeown suggested.

In reality, probably multiple factors influence suicide rates over time, he emphasized, and future research should focus on “a number of potential explanations.”

In regard to the controversy over the possibility that SSRI use could increase suicide risk, McKeown stated, “we do not want to scare people away from effective treatment until we have a better understanding of what is going on,” since there is evidence that antidepressants may in fact reduce the risk of suicide.

“We also want to argue for consideration of policies that would provide better access to mental health care,” he added.

An abstract of “U.S. Suicide Rates by Age Group, 1970-2002: An Examination of Recent Trends” is posted at<www.ajph.org/cgi/content/abstract/96/10/1744>.▪