MH Issues Get Short Shrift By Primary Care Docs

Most primary care physicians would be surprised to see what an outside observer learns from discussions of mental health issues during a patient visit, especially when that observer is a video camera.

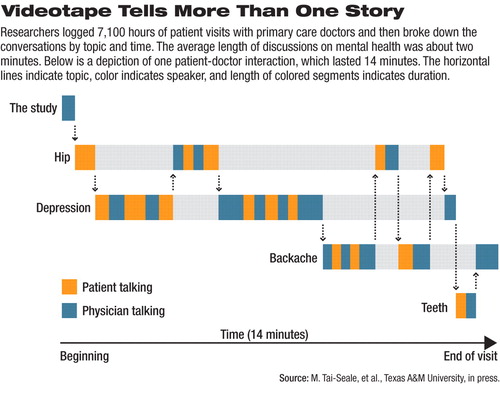

Ming Tai-Seale, Ph.D., M.P.H., and colleagues got consent to videotape 395 patient visits in the offices of 35 primary care doctors, logging 7,100 hours of tape in all. Tai-Seale is an associate professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the School of Rural Public Health at Texas A&M University Health Sciences Center.

They used a mixture of qualitative and quantitative approaches to break down the taped conversations by topic and time. A system that allowed them to graphically portray the patient-doctor interaction helped them analyze how long each person talked, on what subject, and when during the visit any subject came up (see diagram).

The patients were all over 65 years old, 65 percent were women, and 79 percent were white.

Physicians spoke for a median of 3.1 minutes, and patients talked for a median of 5.1 minutes on mental health topics. The majority of mental health discussions lasted about two minutes, but ranged from 14 seconds to 17 minutes. Many of these interactions were discouraging to watch, said Tai-Seale.

In one visit, the patient said: “I've just been crying my eyes out.”

The doctor replied, “Why?”

“I don't know,” said the patient. “People ask me how I am, I just cry.”

“Oh, well. I am not going to ask you that anymore...,” said the doctor.

“A short talk indicated a poor-quality interaction, but a long talk was not much better,” said Tai-Seale at the 13th Annual Biennial Research Conference on the Economics of Mental Health in Bethesda, Md. The conference was sponsored by the National Institute of Mental Health.

“It shows how much time it takes and how hard it is to deliver good mental health care in a primary setting,” said Howard Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, commenting on Tai-Seale's talk. He praised the research for marrying quantitative analytic capabilities with qualitative data acquisition.

There were exceptions, but overall Tai-Seale found that mental health was only infrequently assessed, that the physicians had poor knowledge of psychopharmacology, and that they offered patients little empathy even when it was clear the patients were in distress. A biopsychosocial model was rare, and there were inadequate suicide-prevention responses.

After discussing some psychiatric problem, the physician's response was often inappropriate (suggesting benzodiazepines or polypharmacy, for example), inadequate (“I want you to promise me that you won't shoot yourself”), or missing (“I feel sorry for you, too”).

The results show that the ideal of primary care as an “advanced medical home” is still dysfunctional, said Tai-Seale. “We need systemic change.”

Such change would mean grounding primary care mental health interactions in a biopsychosocial model of medicine, rather than a purely biomedical one, she pointed out. Primary care physicians need to improve their professional competence in mental health even as they team with other professionals with complementary knowledge and skills. They must also allot sufficient contact time and allow themselves to form a genuine emotional connection to the patient, she suggested.

It was hard to know if higher payments to physicians might improve the quality of these visits, said Goldman. “I'm not sure if providing more money is a good idea if the quality of care is so low.”

Like Tai-Seale, he favored implementation of a care model that would permit even a short visit to deliver better care. ▪