Exhibit Reveals What's Behind Faces Of People With Mental Illness

How well can you get to know more than 50 people in the space of, say, an afternoon?

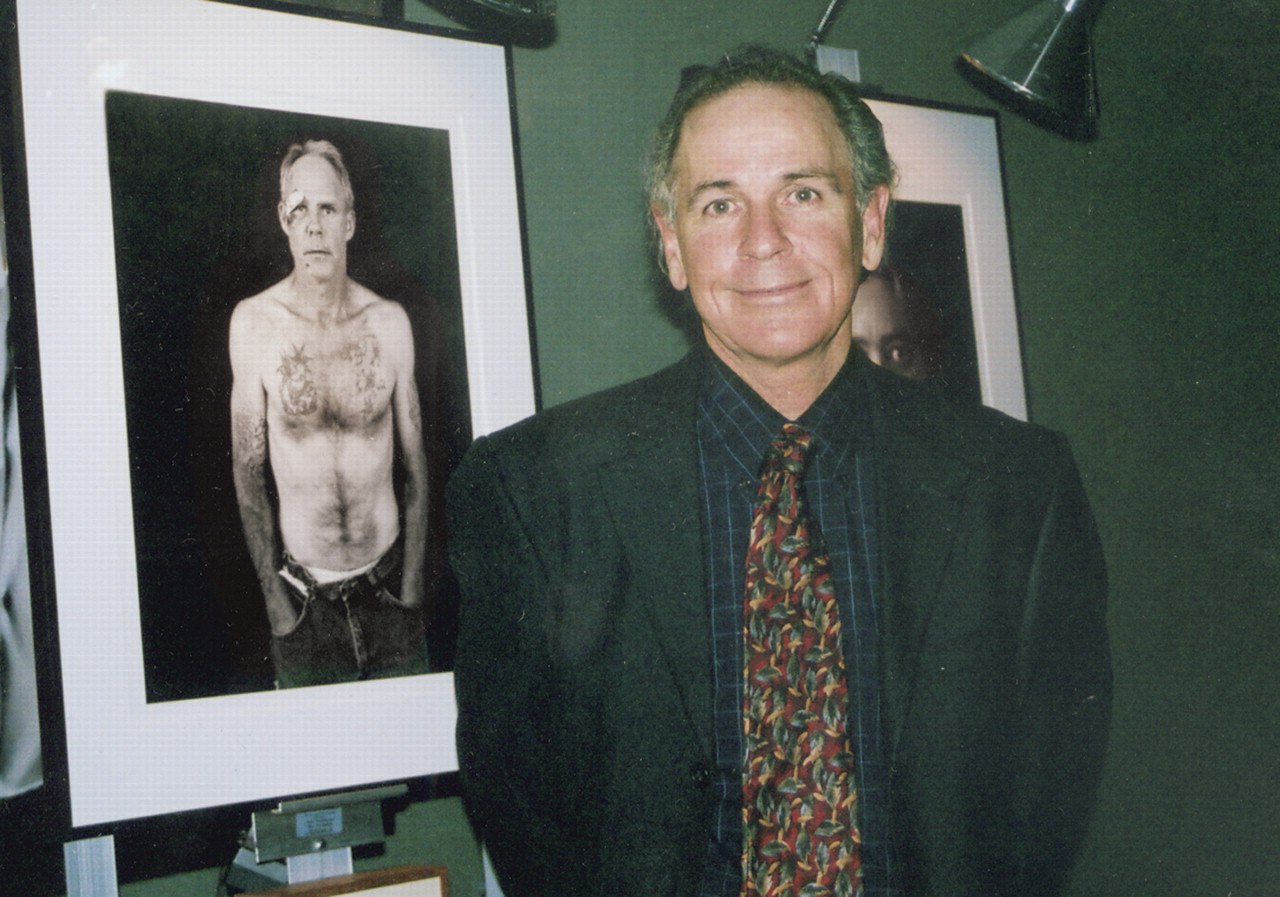

Pretty well, if you are a visitor to Michael Nye's photography exhibit,“ Fine Line: Mental Health/Mental Illness,” which features the images and voices of 55 people with mental illness.

The exhibit opened at the Witte Museum in San Antonio in October 2003 and has traversed the country since that time, educating spectators at museums and medical schools about what it is like to live with mental illness.

Each black-and-white photo tries to capture the essence of Nye's subjects, who happen to be professors, parents, writers, artists, and war veterans.

But it is their audiotaped stories, which touch upon universal themes of fear, alienation, redemption, hope, and survival, that ultimately reveal Nye's subjects to those who stand in front of them, gazing and listening.

According to Nye, people often find something in common with the men and women in his photographs.

“We might find ourselves saying, `that is not unlike my story or my sister's story,'” Nye said to a crowd of consumers, mental health professionals, and government officials who came to the headquarters of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Md., to catch the exhibit in January.

“When you get underneath the surface of what mental illness looks like, you really see that someone's life is more than the illness,” Nye observed. “You see them as human beings first.”

The exhibit features Jamie, who was presented to her community as a debutante at the age of 16 and has skied the Swiss Alps. Though she considers herself to be well-educated, she was homeless and pregnant at the time Nye met and interviewed her.

She is also an Operation Desert Storm veteran and lives with posttraumatic stress disorder and debilitating panic attacks and depression. “I try every day to make a difference in somebody else's life, so that my life will count for something,” she said in her audio segment.

A photograph of Jerry, a tattooed and scarred man, conveys the defiance and vulnerability of a man who recalls that he was first hospitalized for psychiatric problems at age 6, has spent time in jail, and believes that the public should be better educated about bipolar disorder.

Since he met and interviewed him a few years ago, Jerry has died, Nye said.

Beth, another of Nye's subjects, said she endured physical and sexual abuse as a child and was deprived of food. Today she is a poet and lives with agoraphobia, among other mental health problems. In her poems she speaks of“ kindness, hush, and libraries,” Nye said.

Nye told Psychiatric News that he was inspired to create the Fine Line exhibit after a close friend committed suicide. “He had everything. He was a leader, an athlete, and an artist who drew and painted,” Nye said.

His friend was also an architect and at a young age built a house that was featured in an architectural magazine. He was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his 20s and committed suicide in his mother's garage in his 40s.

“He was gentle, kind, intelligent, and shy,” Nye said of his friend. “He once told me, `I can't go on delivering the mail everyday.'”

Nye found his subjects in and around San Antonio by speaking about his project to local mental health support groups such as those sponsored by the National Alliance on Mental Illness. It took him four years to recruit volunteers, interview and photograph each person, and mount the displays.

One of the things Nye learned while working on the exhibit was that“ when you get underneath the surface of what mental illness looks like, you really see that their lives are about jobs, ethical foundations, and families—things we all want.”

He decided to name his exhibit Fine Line because “we are all on that fine line between mental health and mental illness.”

A number of his subjects told him they never believed that they would have mental health problems, Nye said. “They told me, `I always thought it was that person over there, but never me.'”

More information about the Fine Line: Mental Health/Mental Illness exhibit is posted at<www.michaelnye.org/fineline>.▪

Eve Bender

Jerry (in photo at left behind photographer Michael Nye) died not long after this photo was taken. Jerry had spent time in jail due to his mental illness and felt strongly that the public needed to be better educated about mental illness.