Dual Eligibles Faced Serious Health Problems in Shift to Part D

Darrel Regier, M.D., director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, addresses reporters at the press conference.

Credit: Sylvia Johnson

Patients with psychiatric illness who are dually eligible for the Medicaid and Medicare programs experienced serious barriers as they transitioned last year from the Medicaid program to the Medicare Part D prescription drug program to obtain their medications, according to a study by the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education.

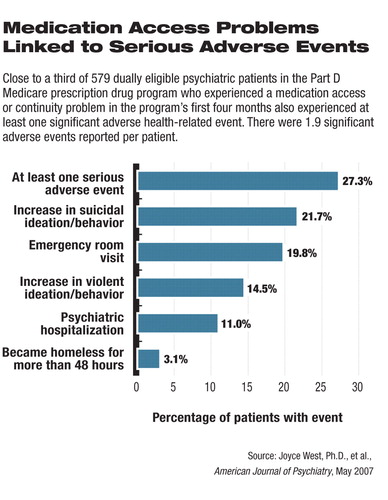

Further, for many patients those access problems resulted in severe consequences including suicidal or violent ideation or behavior, emergency room visits, hospitalization, and homelessness (see chart).

The study covered the first four months of the Part D Medicare program—January 1, 2006, through April 30, 2006. The results were announced earlier this month at a press conference in Washington D.C., and were published in the May American Journal of Psychiatry.

The rollout of the Part D program was plagued by widespread problems including reports that patients were being charged inappropriate copayments, pharmacies were unable to confirm eligibility in the program, and drug plans were failing to have transition policies in effect for the 6 million dual-eligible beneficiaries affected by the change.

“Even though policies were in place [to ensure that beneficiaries continued to have access to medications], prescription drug plans did not adhere to them,” said James H. Scully Jr., M.D., APA medical director, at the press conference.

So severe were the problems that by February of last year about half the states and Washington, D.C., had taken emergency action to continue prescription drug coverage under state financing until problems with the new federal program could be fixed (Psychiatric News, February 3, 2006).

The APIRE study showed that the complaints were far from merely anecdotal as reported in the media at the time.

“This [study] is a realistic view of the problems that this extremely vulnerable population is facing in our public-financed systems of care,” Darrell Regier, M.D., M.P.H., one of the study authors, told Psychiatric News before the study results were announced. “We know that it wasn't easy for these people to get their medications in the Medicaid program, but what this has demonstrated is that for these severely ill patients, [the switch to Part D] was not an improvement in terms of offering greater treatment accessibility.

Minnesota psychiatrist Elizabeth Delesante, M.D., discusses her office's experience after Part D was rolled out on January 1, 2006.

Credit: Sylvia Johnson

“It was asking this population, many of whom have the added burden of cognitive impairment due to their illness, to negotiate an even more complex set of barriers to a managed pharmacy benefit to obtain their medications.”

For example, for many dual-eligible beneficiaries, even choosing a drug plan was fraught with complexity.

Regier is director of the APA Division of Research and executive director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education (APIRE).

Many of the medication access problems that the study identified in the first four months of the Part D program have persisted, at least throughout 2006, according to as-yet-unpublished data.

“We have continued to monitor the program through the end of 2006,” said lead author Joyce West, Ph.D., director of the APA Practice Research Network. “We did expect some of these access problems to be associated with the rollout, but what we have seen is that the rate of problems continues to be problematic. We haven't seen any decline.”

Part D for psychiatric patients “wasn't working in January of 2006 and it isn't working in May of 2007,” said Elizabeth Delesante, M.D., a Minnesota psychiatrist, who discussed her office's experience with the program during the press conference.

The researchers expect to release the data from the rest of 2006 later in the summer.

First to Assess Psychiatric Problems

The study was the first to compile clinically detailed, national data on the impact of drug-plan management practices under Medicare Part D on psychiatric patients' medication access, compliance, and clinical outcomes. It was funded by the American Psychiatric Foundation and a pharmaceutical industry coalition, although APIRE maintained total control of the design, execution, and analysis of the study data.

In the study, 1,183 psychiatrists (35 percent of those contacted) met study eligibility criteria of treating at least one dual-eligible patient during their last typical workweek and reported clinically detailed information on one systematically selected patient. The average patient in the sample had six weeks to accrue a medication access problem during the study's data-collection period.

The researchers found that 53.4 percent of the patients in the study had at least one medication access problem in the first four months of the Medicare Part D program. Although 9.7 percent experienced improved medication access, 22.3 percent discontinued or temporarily stopped taking medication because of prescription drug coverage or management issues.

Among the findings that most disturbed the study authors was that 18.3 percent of patients who were clinically stable on a medication prior to January 1, 2006, were required to switch their medication because it was not covered by the drug plan in which they were enrolled.

“This is particularly troubling because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] had an explicit policy stating that prescription drug plans could not require clinically stable patients to switch their medications,” West told Psychiatric News.

For many patients, West said, the access problems resulted in“ devastating” life changes (see chart).

Regier said the findings clearly call for remediation by CMS.

“What we hope is that this will provide some guidance to CMS, which did a lot to try to mitigate barriers for this group in the rollout,” he said. “If that means some kind of special-needs-population administration for this group, then that is one of the things we think ought to be looked into. The study does not prescribe a solution, but it does indicate that a solution needs to be found.”

Irvin “Sam” Muszynski, J.D., director of APA's Office of Healthcare Systems and Financing, said medication access under the Part D program is dependent on private insurance programs following the law and CMS guidance and not “changing the rules on a daily basis.” APA leaders have discussed increased enforcement of the existing regulations with CMS officials, but prefer that the insurance plans voluntarily adhere to the regulatory requirements. To that end, APA sent letters to all Part D drug plans shortly before the study findings were released urging urged them to adhere to the CMS formulary guidelines designed to protect patient access to psychiatric medications.

Regarding legislation, APA has aimed to “put more teeth in the policy” by having Congress add the regulatory CMS guidance—which includes measures to expand access to psychiatric medications—to an update of the Medicare law. APA supports an amendment by Sen. Gordon Smith (R-Ore.) that would codify the regulations as part of legislation authorizing CMS to negotiate drug prices.

The findings reinforce the anecdotal evidence that mental health advocates are still collecting from Part D participants nationwide. Jennifer Bright, vice president of State Policy for Mental Health America, said her organization has received hundreds of calls since Part D was implemented that detailed psychiatric medication access problems. Although the volume of calls has decreased in recent months, her organization has seen no evidence that the access problems have been addressed beyond the intervention of regulators in isolated cases.

Similar drug-access problems were reported in surveys of HIV medical care providers released the same day as the APIRE study. The survey of 561 providers by the American Academy of HIV Medicine and the HIV Medicine Association reported that 83 percent of clinicians had patients with problems getting their prescriptions since joining a Medicare drug plan. Another 45 percent of clinicians reported that prior authorization was required—counter to CMS regulations—for patients to obtain antiretroviral drugs.

“Toying with antiretroviral drug needs of patients is nothing short of a life-and-death matter,” said Christine Lubinski, executive director of the HIV Medicine Association, at the press conference.

Policy Changes Called For

For some observers, the dramatic nature of the findings—confirming the worst fears of mental health advocates prior to the rollout—also raises questions about the larger public-policy intentions behind the Medicare Modernization Act, which created Part D.

“Specifically, what about the overarching policy preventing the federal government from negotiating prices with the pharmaceutical industry, as the [Department of Veterans Affairs] currently does?” wrote psychiatrist David Pollack, M.D., in an editorial accompanying the report.

“This is clearly an important issue, which is finally getting serious consideration in Congress. Another concern is the overwhelmingly complex array of for-profit and other prescription drug plans associated with the original legislation's intent to privatize the management of this Medicare benefit. This is a condition that seems to guarantee a very chaotic and unregulatable system of access and utilization management, leading inevitably to decreased overall access and quality of care.”

Pollack is a professor of public policy in the departments of psychiatry and public health and preventive medicine at the Oregon Health and Science University.

At the same time, Pollack cautioned against a “nostalgic longing” for the “good old days” of Medicaid coverage for prescription drugs for the psychiatrically ill dual-eligible population. He noted that 19 states had some form of restrictive access by means of prior authorization or other formulary limitations.

Still, it is clear from the study that Part D is not the answer it was intended to be.

“The need for a more consistent approach to ensuring access may require a national system, but not the one that the current Medicare Part D policies have created,” Pollack wrote. “We need to carefully reprioritize our health system values to provide for patients' needs, especially those with the greatest level of severity and acuity, rather than assuring windfall revenues to large corporations.”

“Medication Access and Continuity: The Experiences of Dual-Eligible Psychiatric Patients During the First Four Months of the Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit” is posted at<http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/164/5/789/>. Pollock's editorial, “Medication Access and Continuity Under Medicare Part D,” is posted at<http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/164/5/700>.▪

Am J Psychiatry 2007 164 789

Am J Psychiatry 2007 164 700