Hindsight May Compromise Expert-Witness Objectivity

When psychiatrists offer expert opinions, such as in malpractice cases involving suicide or violence, they should, of course, do so objectively. Nonetheless, they may be subject to hindsight bias, a study in the March Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law suggests.

Hindsight bias is the tendency for persons who already know an outcome to exaggerate the degree to which they had predicted it. In common parlance, one might call it “Monday-morning quarter-backing.”

The lead investigator was Herbert LeBourgeois III, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Tulane University, and the senior investigator was Paul Appelbaum, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, medicine, and law at Columbia University and a former APA president.

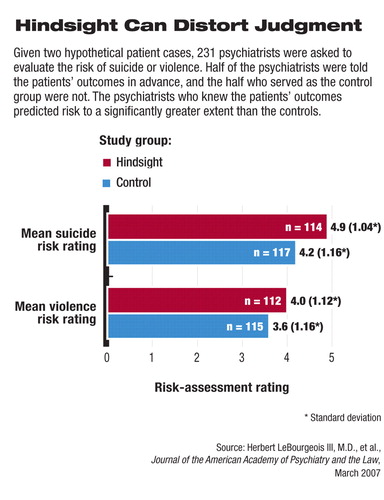

Each of 231 psychiatrists participating in the study was asked to assess risk in a hypothetical case of suicidal ideation and in a hypothetical case of homicidal ideation. Half the subjects were told in advance that the hypothetical patients eventually committed suicide or homicide; the other half were not told this.

The group that had been told the patients' outcome in advance rated them at a higher risk of suicide and violence than did the group that had not been so alerted. The difference was statistically significant, a finding that the investigators had anticipated, especially since a previous study had found that when anesthesiologists review cases with adverse anesthetic outcomes, they are vulnerable to hindsight bias.

This result, LeBourgeois told Psychiatric News, “has potential relevance to psychiatrists providing opinions in malpractice cases (or peer-review evaluations) involving suicide or violence. If, during such retrospective evaluations, evaluating psychiatrists unknowingly exaggerate the risk of suicide or violence posed by patients, they could overestimate the causal role of the actions or omissions of the psychiatrist under review.”

Other findings from the study suggest that even if psychiatrists are susceptible to bias in estimating suicide or violence risk, they may not necessarily be biased in determining whether the psychiatrist caring for the patient at risk was negligent.

Specifically, the group that had been told in advance about the outcomes in the two hypothetical cases was asked to determine whether the psychiatrists caring for the patients had been negligent. The group that had not been told in advance of the outcome was asked to do the same. There were no statistically significant differences between the assessments of the two groups, implying that hindsight bias did not affect this particular type of evaluation.

This was “a somewhat reassuring result,” the investigators said in their report, because it suggested that “ultimate determinations of negligence in malpractice cases may be less affected by hindsight bias than estimates of violence or suicide risk are.”

Another notable finding emerged regarding psychiatrists who specialize in forensic psychiatry. The investigators examined hindsight-bias results depending on whether subjects were members of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law (AAPL) or members of only APA. Although both AAPL and APA subjects who had been told in advance about outcomes were more susceptible to hindsight bias than were their control counterparts, the difference was statistically significant only for the APA-member group.

This finding surprised him, LeBourgeois said. It suggests “that forensic training, forensic experience, or ongoing continuing medical education related to forensic work may serve as buffers to hindsight bias.”

“The data suggest a good news/bad news picture,” Appelbaum added. “Psychiatrists are not immune from hind-sight bias when assessing malpractice cases—that's the bad news. It means that defendant psychiatrists may be at risk of judgments... that are not entirely fair. However, the good news is that greater familiarity with the forensic setting seems to neutralize the biasing effect of knowing the outcome. This suggests that psychiatrists without forensic training who are considering acting as expert witnesses in malpractice cases would be wise to get some significant degree of education and supervised experience first.”

The study had no external sources of funding.

An abstract of “Hindsight Bias Among Psychiatrists” is posted at<www.jaapl.org/cgi/content/abstract/35/1/67>.▪

J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2007 35 67