Geography Test Gives Clues to ALS Patients' Mental Health

Losing control over your movements and knowing that you may die by suffocation are not pleasant prospects. Nonetheless, some patients with end-stage amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) have been found to maintain surprisingly positive outlooks.

This was illustrated, for example, in a study by Judith Rabkin, Ph.D., of Columbia University, and coworkers in which they evaluated the mental health of 80 late-stage ALS patients. As they reported in the July 12, 2005, Neurology, 81 percent had no depressive disorder at the start of the study, 57 percent had no depressive disorder at any visit, and there was no trend toward increasing depression as death approached.

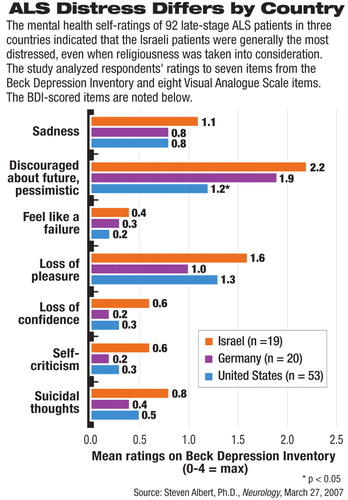

But it appears that the mental health of patients with end-stage ALS may depend on what country they live in, a study in the March 27 Neurology suggests. The investigation was headed by Steven Albert, Ph.D., a professor of behavioral and community health sciences at the University of Pittsburgh's Graduate School of Public Health.

Albert and his coworkers used the Beck Depression Inventory and the Visual Analogue Scale to assess the mental health of 92 patients with end-stage ALS. The patients were similar in sociodemographic features, disease severity, proximity to death, and lack of use of invasive mechanical ventilation, but resided in Germany, Israel, or the United States. “We went into the study without a clear idea of how far cultural differences might matter,” Albert told Psychiatric News.

But they did seem to matter. The most distress was generally reported by the Israeli patients, the least by the American patients, and a middle amount by the German ones.

For example, the Israeli patients were the most pessimistic about the future, the German patients somewhat less, and the American patients the least pessimistic. The difference in pessimism between the Israeli patients and the American ones was statistically significant. Moreover, the Israeli patients reported the most suffering, the German ones somewhat less, and the American ones the least. And even where the German patients scored better on mental health self-rated scales than the American patients did—for instance, they perceived themselves as being somewhat less of a burden on their families than did the latter—the Israeli patients nearly always scored worse than both their German and American counterparts.

Could differences in religiousness explain the differences in distress among the three groups? Albert's team does not think so, because even when the researchers took religiousness into consideration, it did not alter the differences among the three groups in reported distress.

Might Israel's political strife explain the Israelis' low scores? It's a possibility, Albert acknowledged, “but I don't think so.” Rabkin agreed. In fact, she said, she expected the Israeli patients in the study to have the best mental health, not the worst, “given their long training in `stress' associated with” the wars and terrorism that have plagued their country.

Albert and his team believe that one reason why the American patients were least distressed and the Israeli patients the most may be because the former had better palliative care. For instance, they pointed out that the American ALS patients were routinely referred to hospice care, with nearly 80 percent using such care before death, whereas the Israeli patients received good respiratory, speech, and swallowing services, but no hospice care.

The National Institute of Mental Health and the Fetzer Institute funded the study.

An abstract of “Cross-Cultural Variation in Mental Health at End of Life in Patients With ALS” is posted at<www.neurology.org/cgi/content/abstract/68/13/1058>.▪

Neurology 2007 68 1058