Genetically Engineered Mouse Mimics Schizophrenia

A mouse model that mirrors schizophrenia-like traits would go a long way to help researchers explore the causes and test cures for the disease. So far, the nearest scientists have gotten is dosing rodents with amphetamine or phencyclidine to mimic behavior typical of schizophrenia.

A team led by Johns Hopkins researchers, however, has now developed the first transgenic mouse with a mutated gene that produces both behavioral and anatomical deficits similar to those associated with schizophrenia in humans.

“We have produced a significant, if subtle, change in phenotype that can be used to test other factors or serve as a drug screen,” said Akira Sawa, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience and director of the program in molecular psychiatry at Hopkins, in an interview. Sawa led the 15 researchers who developed the mouse.

Mouse models have been developed “extremely slowly,” Douglas Meinecke, Ph.D., program officer in the Clinical Neuroscience Research Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health, told Psychiatric News. Another eight or 10 mutant genes have been identified, and some have been inserted into mice.

Schizophrenia is a heterogeneous disease with multiple symptoms and causes, including genetic, said Meinecke.

Sawa and colleagues created two mouse lines with a dominant-negative disrupted-in-schizophrenia (DN-DISC1) gene. Proteins expressed by DISC1 are involved in dendritic outgrowth and development of the cerebral cortex. Mutated versions of the gene have been tied to susceptibility for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression and correlated with psychiatric disorders in an extended Scottish family, according to research published in the September 4 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“So far we've seen a lot of weakly related gene studies with small effects, including DISC1,” he said. “Now we need to perturb the gene and see what happens. What's wrong, why is it wrong, and how does it work? The new mouse models may let us look at real potential mechanisms for how the disease works.”

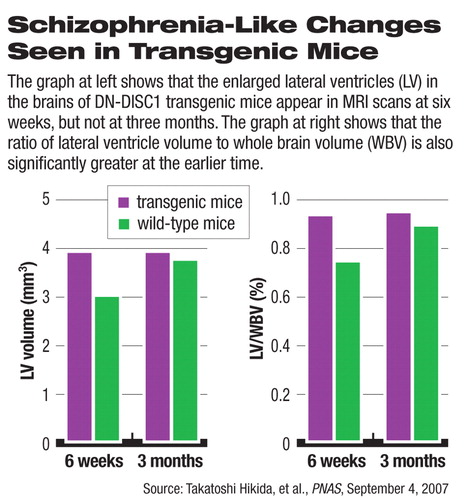

Sawa's team found indications of anatomical changes in the transgenic mice. Left-to-right asymmetry in the lateral ventricles found in unmutated mice was lost or reversed in the DN-DISC1 mice. At 6 weeks of age, the lateral ventricles in the brain were significantly enlarged, although that difference disappeared at age 3 months.

“Enlarged ventricles are important biomarkers for schizophrenia, but that is only one of several facets of the disorder and not diagnostic,” said Sawa.

The researchers could not explain the initial, temporary enlargement of the ventricles.

Nevertheless, because schizophrenia usually develops between the ages of 18 and 24, changes in ventricle size at least imply some role for DISC1, said Meinecke. “Simply the fact that the researchers found neurodevelopmental differences at all is important,” he said.

They also found deficits that underlie abnormal neural synchrony and impaired sensorimotor gating, according to Sawa and colleagues.

“Consistent abnormalities of such [schizophrenia]-associated changes can suggest that the present mouse model may mimic at least a subset of human [schizophrenia],” the researchers wrote. “Our results indicate that the enlargement of DISC1-DN is associated with deficits in neurodevelopment, but not with the process of progressive neurodegeneration.”

Behavioral tests found an increase in hyperactivity, especially late in the trials, when ordinary mice should have gotten used to their surroundings. Transgenic mice took longer to find food, possibly reflecting problems either with their sense of smell or a lack of motivation. Tests for anxiety, motor coordination, and spatial learning produced no differences.

A related study in the September 11 Molecular Psychiatry by Sawa's co-author and Hopkins colleague, Mikhail Pletnikov, M.D., Ph.D., found that, compared with controls, DISC1 transgenic male mice also displayed alterations in social interaction, and transgenic female mice showed deficient spatial memory, behavior similar to some features of schizophrenia.

Sawa and his colleagues will next use positron emission tomography to visualize neural transmission and metabolism in the mice to help correlate the animal model to effects in human tissue, he said. They will also collaborate with other researchers, supplying mice to test how perinatal or prenatal stressors (such as some infectious diseases like toxoplasmosis) may affect the phenotype.

The research was supported by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service, the Neurogenetics and Behavior Center at Johns Hopkins, the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the Stanley Medical Research Institute, and the S-R Foundation.

An abstract of “Dominant-Negative DISC1 Transgenic Mice Display Schizophrenia-Associated Phenotypes Detected by Measures Translatable to Humans” is posted at<www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/0704774104v1>.▪