Physiological Measures May Aid Conversion Disorder Diagnosis

Stimulating affected and unaffected limbs of patients with conversion disorders confirms the psychogenic nature of the condition and may lead to better understanding of the neural processes involved, said three researchers in the December 12, 2006, Neurology.

Omar Ghaffar, M.D., M.Sc., and Anthony Feinstein, M.D., M.Phil., of the Department of Psychiatry, and W. Richard Staines, Ph.D., of the Department of Neurology, at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center at the University of Toronto, studied responses of three patients meeting DSM-IV-TR criteria for unilateral conversion disorder, sensory subtype.

The site of sensory loss in one patient was the left hand, while the other two had lost feeling in the left foot.

Vibrating stimulation was applied to the limbs as the brain was scanned by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Normally, the primary somatosensory (S1) region—in these cases, the orbital frontal cortex or the anterior cingulate—on the opposite side of the brain from the affected limb will be activated by a stimulus.

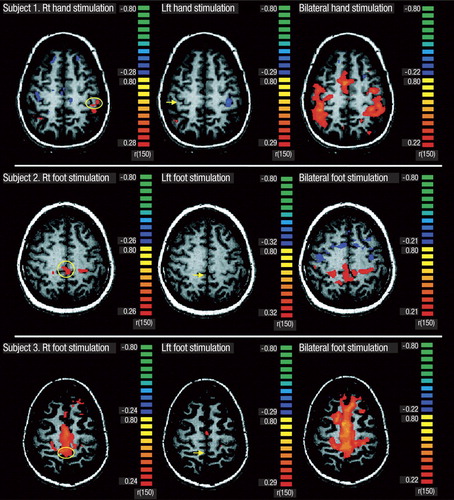

First, the researchers stimulated only the left, affected limb, which failed to activate the appropriate region on the opposite side of the brain. Stimulation of the opposite, unaffected hand or foot produced activation as expected and as seen in healthy controls.

However, the most interesting result came when both affected and unaffected limbs were stimulated simultaneously, activating the orbital frontal cortex and the anterior cingulate in both hemispheres.

“Our methodology, comprising both unilateral and bilateral passive stimulation, bridges the two seemingly contrary S1 findings in the literature: unilateral, unlike bilateral stimulation of an affected region, is insufficient to activate the appropriate contralateral S1,” they said.“ Why this should be is unclear. One possible mechanism is that bilateral stimulation acts as a distractor that overcomes the inhibition on S1 that occurs with unilateral stimulation.”

Activation of other areas of the brain previously implicated in conversion disorder—such as the orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate, striatum, or thalamus—proved inconsistent, somet hing that other researchers have also found, they said.

Explaining the Unexplained

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of three subjects with sensory conversion disorder reveals activity varying with stimulation patterns. Left column: Stimulation of the limb in which sensation is intact activates the primary somatosensory region on the contralateral side of the brain (circled). Middle column: No such activation occurs during stimulation of the affected limb (arrows). Right column: However, simultaneous stimulation of the limb in which sensation is intact and the affected limb activates the primary somatosensory regions on both sides of the brain (red).

Source: Omar Ghaffar, M.D., et al., Neurology, December 12, 2006

Conversion disorders are major concerns for neurologists and psychiatrists, said W. Curt LaFrance Jr., M.D., director of neuropsychiatry at Rhode Island Hospital and an assistant professor of psychiatry and neurology (research) in the departments of psychiatry and human behavior and of clinical neurosciences at Brown Medical School.

Unexplained sy mptoms often lead physicians to order “just one more” test to try to find some anatomic basis for the patient's complaint, LaFrance told Psychiatric News.

“An N of three may be a good place to begin research, but that doesn't make it definitive,” he said. “However, this study is helpful. For most psychiatric diagnoses, we don't have a physiological measure to confirm our observations, but if we could better understand somatoform disorders from a neurophysiological and neuroanatomic perspective, we could move forward.”

“Our study is one of no more than half a dozen published so far to look at conversion disorder with fMRI,” said Feinstein in an interview.“ All of them are small. I think that reflects the limitations on brain imaging until recently, but the development of fMRI opens up possibilities.”

Much psychoanalytic and behavioral theory has been devoted to conversion disorder, he added, but only a tiny literature addressing its neural basis. Functional brain scanning seems to mirror early psychiatric thinking about conversion disorders, he pointed out.

“In the 1880s, Sigmund Freud said that the brain was abnormally challenged by emotions, using up energy and turning off neural circuits, which resulted in physical symptoms,” said Feinstein. “Our data are only tentative, but I think Freud would be intrigued.”

The three cases in the study were well confirmed as not having a neurological cause, said Feinstein. Misdiagnosis of conversion symptoms in clinical studies was reported at a rate of 29 percent in the 1950s, but that dropped to 4 percent in the last decade, according to a meta-analysis published in the October 29, 2005, BMJ (British Medical Journal).

Improved study methods and clearer case definition, rather than new technology, probably caused this reduction, wrote Jon Stone, M.D., a consulting neurologist at the School of Molecular and Clinical Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and colleagues in BMJ.

“While concern about misdiagnosis may be helpful in encouraging a thorough assessment, it may be unhelpful by leading to overinvestigation and delayed treatment for what are potentially reversible conversion symptoms,” they stated.

“I hope that studies like ours will help put an end to debate on physical versus functional in conversion disorder,” said Feinstein.“ The distinction is not helpful when it comes to treating patients. Patients find the clear evidence of functional brain change comforting because it validates what they are experiencing.”

These results do not indicate that fMRI is ready for prime-time diagnostic use, cautioned Feinstein. “But they do open a new door for research.”

“We're continuing to scan patients and now have data from a total of 10,” he noted. Feinstein declined to comment on these newer results before data analysis is complete.

For the moment, Feinstein favors behavioral therapies for these patients to work on their distorted cognition and to structure day-to-day activities. In addition, antianxiety medications may be useful occasionally, he said.

“As far as we know, these authors are the first to have visualized this reversible malfunction at the level of neural clusters large enough to change the signal from MRI voxels,” commented Trevor Hurwitz, M.B.Ch.B., of the University of British Columbia and James Pritchard, M.D., of Yale Medical School in an accompanying editorial in Neurology.“ Their findings add to the growing body of data that implicates attention and active inhibition in the conversion process and thereby helps integrate bedside observation with brain mechanisms.”

Combining the patient's experience with fMRI findings “opens a new window on the problem,” they said.

“Unexplained Neurologic Symptoms: An fMRI Study of Sensory Conversion Disorder” is posted at<www.neurology.org/cgi/content/full/67/11/2036>; the editorial “Conversion Disorder and fMRI” is posted at<www.neurology.org/cgi/content/full/67/11/1914>.▪