Insurance Coverage Interruptions Linked to Treatment-Cost Increases

Medicaid beneficiaries with depression who returned to the program after a temporary loss of coverage cost the program more and needed to use more services than they did before their coverage was interrupted.

The jump in costs and utilization of inpatient and emergency-room services was especially pronounced among beneficiaries with a documented disability. The study followed several research studies that found that people who need medical care reduced their care when they lost public or private insurance.

“Given these previous findings, it is reasonable to presume that when most individuals lose their Medicaid coverage, they stop consuming health services,” wrote the study authors. “For some individuals, especially those with chronic conditions, health status may deteriorate to the point where acute care is needed.”

The study, “Changes in Health Care Use and Costs After a Break in Medicaid Coverage Among Persons With Depression,” by Jeffrey Harman, Ph.D., and colleagues at the Florida Center for Medicaid and the Uninsured at the University of Florida, appears in the January Psychiatric Services.

The findings are similar to another study that found Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia who had disruptions in their coverage required significantly more inpatient psychiatric services after coverage was restored than did similar beneficiaries with continuous access to coverage. The study, also by Harman and colleagues, was published in the July 2003 Psychiatric Services.

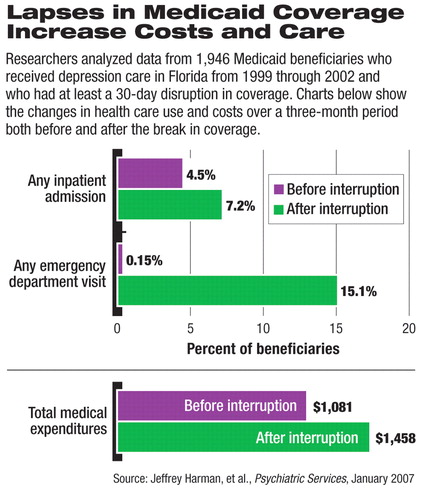

The depression study findings were based on information from 1,946 beneficiaries who received depression care in the Florida Medicaid program from 1999 through 2002 and who had at least a 30-day disruption in coverage. The researchers used the data to assess the beneficiaries' utilization of Medicaid services in the three months before and three months after the period in which they went without Medicaid coverage.

Researchers did not determine the amount of care received during the period in which subjects went without coverage. The period of interrupted coverage ranged from 32 to 1,219 days, with a median of 284 days.

Hospitalization More Likely

The researchers found that the beneficiaries with disruptions in their Medicaid coverage were more likely to undergo hospitalization and to remain hospitalized for significantly more days in the three months after returning to Medicaid than in the three months before losing Medicaid coverage. Among the beneficiaries in the study, 126 (6.4 percent) had more hospitalizations after the Medicaid benefits were interrupted than they did before the coverage interruption, while only 65 (3.3 percent) had fewer hospitalizations after their benefits were disrupted. There were no changes in hospitalizations among the other study beneficiaries.

The researchers also found a 170-fold increase in the number of emergency-room visits after the coverage was interrupted. The study found that 295 beneficiaries (15 percent) whose Medicaid coverage was interrupted had an increase in emergency-care visits after they were again covered by Medicaid. One beneficiary had fewer emergency visits, and 1,653 had no change in the three months after their Medicaid coverage was restored.

“This finding suggests that the emergency department serves as a major entry point for people returning to care,” said the researchers. They speculated that the emergency-care visit may have been the catalyst for the beneficiaries' re-enrollment in Medicaid, but they did not explicitly try to prove that link.

The interval between emergency visits also showed the effect of interruptions in Medicaid coverage. The time between such visits shrank considerably when care was interrupted, with depression patients seeking such care every 170 days after losing and regaining their Medicaid access; these individuals sought emergency care every 206 days before the disruption. The longer the disruption in care lasted, the more likely the individual was to seek out emergency-room care. Individuals with interruptions of less than two months had significantly fewer emergency-care visits after returning to Medicaid than did beneficiaries who lost access to care for more than seven months.

Costs Rise With Coverage Interruption

The study also found that 964 beneficiaries (50 percent) ran up increased expenditures after their Medicaid coverage was restored, while 917 (47 percent) spent less after they returned to the Medicaid program. Beneficiaries who were younger and female were more likely to have increases in expenditures, while older, male, African-American beneficiaries were the least likely group to incur increases in spending.

Individuals who were eligible for Medicaid because of a disability were 28 percent more likely to have an increase in expenditures than were beneficiaries who were eligible through other noneconomic factors such as age or pregnancy. Increased expenditures also were associated with individuals whose Medicaid eligibility continued to stem from their depression-based disability—rather than a disability attributed to another reason.

“Policymakers could use this information to target policies for enrollees who are most likely to be adversely affected by interruptions in coverage,” the authors said, about participants the study found most likely to be affected by the coverage disruptions.

They cautioned that the findings do not establish definitively that access to care and use of care dropped during the periods when the study subjects went without Medicaid coverage, because they have no way of knowing what types of services were used during those intervals. Previous studies found that most Medicaid beneficiaries who lost coverage became uninsured and accessed care much less frequently than when they were covered by the program.

“Changes in Health Care Use and Costs After a Break in Medicaid Coverage Among Persons With Depression” is posted at<http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/58/1/49>.▪