Program Helps Torture Victims Find Solace, Healing

The Canadian Center for Victims of Torture is on the second floor of this office building on Jarvis Street in downtown Toronto.

Photo: Joan Arehart-Treichel

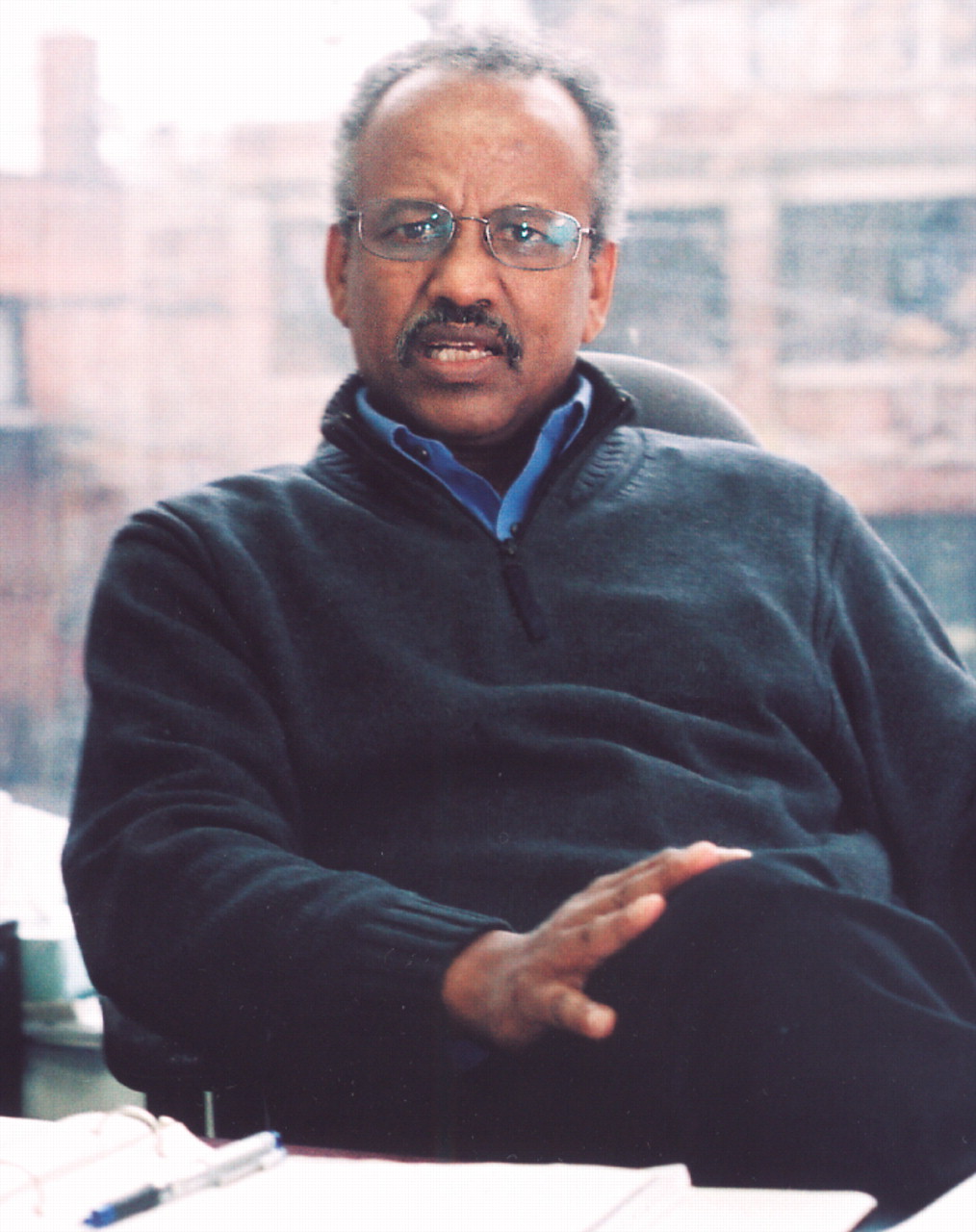

Mulugeta Abai: “We have to break the circle of silence surrounding torture.”

Photo: Joan Arehart-Treichel

If eyes are a window to a man's soul, then those of Ezat Mossallanejed, Ph.D., reflect unspeakable horror. The horror stems from two different experiences—being tortured under the regime of the shah of Iran and then forced into exile by Iranian Islamic fundamentalists.

Mossallanejed's journey eventually took him to Toronto, Canada, where he works as a policy analyst and a settlement counselor in a most unusual place—the Canadian Center for Victims of Torture (CCVT) in downtown Toronto.

The CCVT's mission is to assist individuals who have been tortured for political reasons. It was founded 30 years ago by Toronto psychiatrist Federico Allodi, M.D., and Toronto family physician Philip Berger, M.D., and has helped some 16,000 persons. It was the second such center to be set up in the world and has served as a prototype for more than 100 others that have been formed since, a few of them in the United States.

The center is a safe haven for those who have obtained refugee status and for those who seek it. For instance, Mossallanejed nurtures a small tree in his office. It gives both him and his clients comfort and hope, he explains in a soft voice and gentle manner that belie his haunted past.

The center is also a family for torture victims who have lost theirs—for example, for Emed Abbas, a burly iraqi in a green-checkered jacket who was tortured under Saddam Hussein. “My family is scattered all over the world,” he laments.

Moreover, the center offers torture victims help with legal counseling, assistance in obtaining housing, assistance in obtaining employment, English courses, computer courses, medical care, psychiatric assessments to be presented at their refugee hearings by the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Board, and psychiatric treatment for the psychological consequences of their torture experiences. There are even special services for children whose parents have been tortured or who have been tortured themselves, among which are tutoring, a homework club, art therapy, computer training, and medical care.

Finally, CCVT's services are provided not just by its 15 staff members, but by some 300 physicians, lawyers, and other professionals who, among them, speak 40 languages. The services provided by lawyers and physicians are reimbursed by the Canadian government, but as Donald Payne, M.D., a Toronto psychiatrist and CCVT board member, points out, “With most refugee claims, one has to put in a lot more effort than one gets paid for.”

Multiple Challenges to Overcome

Depending on their particular responsibilities, those helping CCVT clients face different types of challenges.

For example, in spite of trying for 12 years to convince the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Board that a particular torture victim deserves refugee status, Mossallanejed has not managed to do so. Such failures are a downside of his work, he says. Yet another burden, he points out, is continually listening to other people's torture stories while trying to forget his own.

One of the biggest hurdles that Mulugeta Abai, an Ethiopian torture victim and now executive director of the CCVT, faces is raising funds to keep the center afloat. It has been especially difficult since 9/11 because people don't want to think about torture, he explains. “Yet we have to break the circle of silence regarding torture.”

“One of the biggest challenges in helping patients from the CCVT,” Lisa Andermann, M.D., a psychiatrist at Toronto's Mount Sinai Hospital and a CCVT board member, emphasizes, “is that it is difficult to do traditional psychiatric trauma treatment when clients are still uncertain about their immigration status and are facing very practical everyday problems around finances, housing, work, and organizing their daily lives... .Only after issues around immigration are settled, and clients feel secure knowing they can remain in the country, can [such treatment really get under way].”

Payne has assessed or treated more than 1,500 victims of torture and war over the last 28 years. Most have been referred by the CCVT, although some directly by lawyers. At first he was worried that he might not be able to relate to people from cultures vastly different from his own. Yet that has not been a problem, he says. “Once you start talking to these people, they relate back. You quickly pick up on the cultural aspects.”

Interpreters Can Present Barrier

What has been an occasional irritation, though, he admits, is when the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Board complains that his psychiatric assessments of torture victims all sound the same. Yet he sees no easy way to satisfy the board on this point, because the torture victims he assesses have often experienced similar atrocities. And what has been an occasional barrier, he adds, is getting interpreters not just to abstract patients' stories, but to tell him the exact words they used, so that he can get a better sense of what they have experienced and how it has affected them.

Yet even without the involvement of translators, it is not always easy to determine what torture victims have experienced and how these experiences affect their day-to-day functioning, Rosemary Meier, M.D., reports. Meier has assessed or treated some 100 CCVT clients over the past 17 years. “Some people can have very florid symptoms, but function fine,” she says,“ whereas others have symptoms that don't appear to be quite as serious, but that are very detrimental to their ability to continue their lives.”

And the symptoms that torture victims experience, Meier continues,“ depend not just on their torture experiences, but the context of [those experiences].... People who are politically active perhaps realize they are running risks and are in a different situation from those who [experience torture] as a chance encounter.”

To illustrate her point, she cited the example of a woman who had been living in an apartment building in a south american city. “The superintendent came to do a small repair [in her APArtment]. He had been politically active. It was through that that she was trailed, captured, and tortured.”

Payne agrees. “A lot of the people we see have been politically involved, where they know that being politically involved is dangerous. They are prepared in some ways for the risks involved. However, some of the torture victims we see weren't prepared.”

One such person Payne cites is a man whose brother was politically active, but the man was arrested and tortured “just because of their relationship.”

Which symptoms torture victims experience also depends “on where people are at in their lives,” Meier points out. Payne concurs, noting,“ I have seen some 15- and 16-year-olds who were detained and tortured and who did not have the psychological resources that older people have.”

But just as working with CCVT clients presents challenges, it also offers rewards. Mossallanejed said he is particularly proud of two refugees he has helped. One is now a general practitioner in Canada and the other a heart surgeon in the United States.

Abai is especially pleased when CCVT clients find work, then share a little of their income with the center. Their success and generosity “make us feel successful.”

Payne is also delighted when CCVT clients find work because it often means so much to them psychologically. “The bad thing about torture is not the pain itself, but the personal denigration and loss of self-esteem that it inflicts,” he explains. “So it is [especially difficult for torture victims] to come here and be on welfare.... But if they can get work again and support themselves,” they usually do quite well.

Indeed, one of the greatest rewards that Payne has received from treating torture victims is that about 80 percent of them have responded well to treatment and have gotten on with their lives.

“You get a sense of the real human spirit in these individuals,” he declares. ▪