Anxiety Disorders Often Untreated in Primary Care

In a study of 15 New England medical practices, only half the primary care patients with anxiety disorders were receiving treatment, possibly because patients rejected treatment or doctors failed to recommend it. However, both primary care physicians and psychiatrists chose similar medications and dosages when prescribing pharmacotherapy.

“These data suggest that there remains substantial room for further improvement in reducing the burden of anxiety disorders on society,” wrote Risa Weisberg, Ph.D., and colleagues in the February American Journal of Psychiatry.

Such improvement is dependent on a number of factors, including better identification and treatment of patients in primary care settings and addressing barriers that prevent patients from obtaining or seeking the care they need.

Little is known about care in primary practices of patients with anxiety, said Weisberg, an assistant professor (research) in the departments of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and family medicine at Brown University School of Medicine.

To remedy that lack of information, the researchers recruited patients from waiting rooms in primary care practices in New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. The study did not track whether the patients had been diagnosed previously with anxiety.

Those who were interested in participating in the study completed a self-report form designed to evaluate the key features of DSM-IV anxiety disorders. The patients who screened positive for anxiety symptoms were offered a full diagnostic interview using the SCID modules for mood, substance use, and eating disorders; Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; and the Global Social Adjustment Scale.

The research was part of the Primary Care Anxiety Project, which is following patients with anxiety over a period of years. The current report covers only baseline data, gathered from patients who entered the study from 1997 to 2001.

The study was funded by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and a career-development award from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Of the 539 patients with an anxiety disorder ultimately enrolled in the study, 50 percent had more than one anxiety disorder. Many (41 percent) had comorbid major depression, eating disorders (11 percent), or an alcohol or substance use disorder (10 percent).

Only 284 of the patients (52.7 percent), however, were in treatment for their psychiatric diagnoses at the time they were enrolled. Out of that group, 113 were prescribed medication alone, 132 were getting both medication and psychotherapy, and 39 received psychotherapy alone.

“Anxiety is probably underrecognized because symptoms are not presented or visible in the little time in the doctor's office, so the higher-functioning patient slips by,” she said. Many respondents said they were unaware of having any problem, and others said their primary care provider had not recommended treatment.

“Primary care physicians have a hard job,” agreed Wayne Katon, M.D., a professor and vice chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine, in an interview.

“Eighty percent of patients with anxiety disorders present with physical complaints, so their primary physician has to rule out any life-threatening conditions before considering psychiatric diagnoses,” he said. “Vague somatic complaints take precious time to figure out and more time to educate patients and prescribe or refer them to counseling.”

Of the 539 study participants, 245 were being treated with medications, in about equal proportions from primary care physicians (41 percent) and psychiatrists (40 percent). About 7 percent got their medications from other sources.

The most commonly prescribed drugs from all clinicians were SSRIs (60 percent prescribed them) and benzodiazepines (35 percent). The equal use of SSRIs by psychiatrists and primary care physicians suggests the latter know about new developments in treating anxiety. Psychiatrists were more likely to prescribe benzodiazepines, possibly because their patients had more severe anxiety symptoms. The only factor predicting medication treatment from a psychiatrist was the patient's lower score on the Global Social Adjustment Scale. Medicare or Medicaid recipients were more likely to be treated by any type of clinician than were patients with private insurance or no insurance.

“This was a surprise,” said Weisberg, who is still studying this point. “It's not just their ability to pay, but may be a proxy for impairment.”

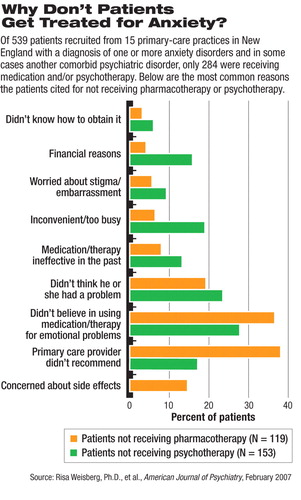

The researchers interviewed a subgroup of patients with anxiety disorder to ask why they believed they were not receiving medication or psychotherapy. Among those not treated with drugs, 39 percent said their primary care provider had not prescribed medications for them. About 17 percent of patients not getting psychotherapy gave the same reason. Almost 20 percent of those not taking medications and 24 percent of those not receiving psychotherapy said they didn't know they had a treatable problem. Furthermore, 37 percent of the unmedicated group and 28 percent of those not getting psychotherapy said they didn't believe in those types of treatment for emotional problems.

Such resistance may have cultural roots, said Weisberg. “We didn't assess this, but I think that people feel that therapy or medication is just not how they cope with problems. They'd rather 'tough it out' or 'get over it.' ”

Weisberg made clear that her study should not be seen as an epidemiological study of anxiety prevalence in private practice.

“Taking subjects out of a waiting room might give greater prominence to 'high attenders,' that is, patients more likely to visit the doctor six or 10 times a year and who have greater psychological distress,” said Katon.

Weisberg's group will continue its research by looking at how outcomes vary by type of clinician to see whether patients in primary care do as well as those under the care of specialists.

“Psychiatric Treatment in Primary Care Patients With Anxiety Disorders: A Comparison of Care Received From Primary Care Providers and Psychiatrists” is posted at<ajp.psychiatryonline.org> under the February issue. ▪