Less-Severe Side Effects Reported When CBT Added to Medication

A certain type of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) aimed at reducing the anxiety associated with symptoms of panic disorder may also help to reduce the severity of medication side effects, according to a study published in the February American Journal of Psychiatry.

Patients treated with imipramine and “panic control therapy” experienced less-severe fatigue, weakness, dry mouth, and sweating. As a result, they tended to stick with the imipramine treatment longer than those who received the medication alone.

According to lead author Sue Marcus, Ph.D., the goal of this type of CBT used in the study aims to reduce “the fear of somatic sensations” related to panic disorder while reducing the perceived severity of medication side effects. In addition, CBT may help decrease the chances that a panic episode may be mistaken for a medication side effect, she told Psychiatric News. Marcus is an assistant professor of psychiatry and biomathematics in the Department of Psychiatry at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine.

Panic control therapy is a 12-session treatment developed by David Barlow, Ph.D., at Boston University. It includes patient education, breathing retraining, cognitive restructuring, and “interoceptive conditioning,” in which patients engage repeatedly in activities that bring about physiological changes such as breathlessness until they understand that these sensations are not harmful.

During cognitive restructuring, patients are trained to avoid catastrophizing normal physiological fluctuations and sensations such as breathlessness or rapid heart-beat.

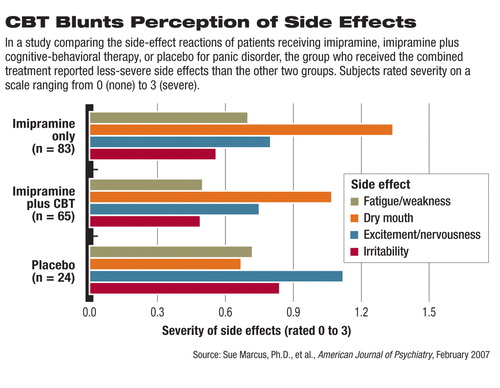

Researchers analyzed data on 172 patients who met criteria for panic disorder and who were enrolled in a multisite study completed in 1998 at anxiety research centers at Boston University, Hillside Division of Long Island-Jewish Hospital, Yale University, and the University of Pittsburgh. Patients in Marcus's study were randomly assigned to receive imipramine (83), imipramine plus CBT (65), or placebo (24).

The study was divided into three treatment phases—a 12-week acute phase during which subjects were seen 10 times for treatment, a six-month maintenance phase in which subjects who responded to acute therapy were maintained on treatment and seen once a month, and a six-month follow-up phase during which treatments were discontinued and subjects were evaluated monthly.

Patients assigned to receive imipramine or placebo began the study by receiving 25 mg daily and could go as high as 300 mg daily for the remainder of the acute phase.

During each of the medication visits, patients were asked whether they were experiencing side effects such as insomnia, sleep disturbance, drowsiness, nervousness, fatigue, irritability, memory problems, impaired cognition, dizziness, headache, or blurred vision.

During the study period, 18 patients dropped out due to side effects. Thirteen patients dropped out during the acute-treatment phase: 11 of the 83 patients who received only imipramine and two of the 65 patients who received imipramine plus CBT. The other five dropped out during the maintenance phase. No patients in the placebo group dropped out.

Marcus found that patients treated with imipramine plus CBT reported overall less fatigue or weakness, dry mouth, and sweating during the three study phases compared with those who received imipramine alone (see chart). The difference was statistically significant.

The placebo group reported greater levels of excitement and nervousness, irritability, headache, and libido decrease compared with the other two groups, which researchers attributed to symptoms of their panic disorder.

Marcus pointed out that given reduced side-effect severity and dropout rates among those who received panic control therapy plus imipramine, combined treatment may in fact be superior for panic-disorder patients.

She acknowledged that her findings are limited by the study's small sample size and need to be confirmed through studies with larger samples. Studies measuring the effect of CBT on patients who are taking medications other than imipramine may also be helpful, she added.

The National Institute of Mental Health funded the study.

The results of “A Comparison of Medication Side-Effect Reports by Panic Disorder Patients With and Without Concomitant Cognitive-Behavior Therapy” is posted at<http://ap.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/collection/cognitive_therapy?notjournal=ap>.▪