Depression Can Break Heart in Unexpected Way

Remember all the hype about the type-A personality a few years ago? This is a person bristling with aggression and hostility. And certainly hostility and anger have been linked with an increased risk of having a heart attack.

However, neither hostility nor anger seems to pave the way for the very early stages of cardiovascular disease, a study published in the February Archives of General Psychiatry suggested.

The researchers found no link between hostility or anger and thickening of the carotid arteries in subjects who were followed over a three-year period. The investigators did find, however, an association between the vegetative symptoms of depression and such thickening over the same time span.

The lead investigator was Jesse Stewart, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis. He conducted the inquiry while he was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Pittsburgh.

Although depression and anxiety, as well as hostility or anger, have been associated in the past with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, Stewart and his colleagues wanted to evaluate the relative contributions of these four negative emotions to the early disease process.

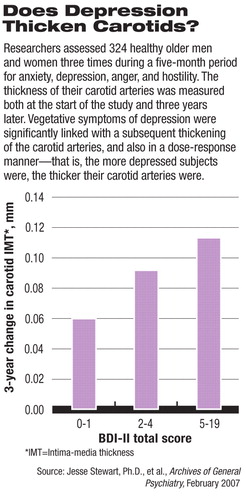

They assessed 324 healthy older men and women for anxiety, depression, anger, and hostility over a five-month period; measured the thickness of the subjects' carotid arteries both at the start of the study and during a three-year follow-up period; and then attempted to see whether they could link each of the four types of negative emotions to thickening of the carotid arteries. In doing so, they took numerous possibly distorting factors—demographics, cardiovascular risk, medication use, medical conditions, and the other negative emotions of interest—into consideration.

They assessed 324 healthy older men and women for anxiety, depression, anger, and hostility over a five-month period; measured the thickness of the subjects' carotid arteries both at the start of the study and during a three-year follow-up period; and then attempted to see whether they could link each of the four types of negative emotions to thickening of the carotid arteries. In doing so, they took numerous possibly distorting factors—demographics, cardiovascular risk, medication use, medical conditions, and the other negative emotions of interest—into consideration.

The scientists were not able to link hostility, anger, or anxiety to thickening of the carotid arteries, but they did find a significant association, and a dose-response relationship, between depression and the latter. In other words, the more depressed subjects were, the thicker their carotid arteries became.

The investigators then looked to see whether particular depressive symptoms could be coupled with thickening of the carotid arteries. Regarding the cognitive symptoms of depression (sadness, pessimism, and indecisiveness), the answer was no, but regarding the vegetative symptoms of depression (loss of appetite and pleasure in life, fatigue, and sleep disturbances), the answer was yes.

“Our findings suggest that the somatic-vegetative features of depression, but perhaps not anxiety, hostility, and anger, may play an important role in the earlier stages of the development of coronary artery disease,” Stewart and his group concluded in their study report.

Stewart told Psychiatric News that the absence of a link between the negative emotions they evaluated and early thickening of the carotid arteries was unexpected. And, he said, “It was also somewhat surprising that only the vegetative symptoms of depression were predictive of greater thickening of the carotid arteries over time.”

He pointed out, however, that hostility, anger, anxiety, and the cognitive symptoms of depression may still play a role in the later development of coronary artery disease. He also conjectured that while the means by which negative emotions might contribute to coronary artery disease are not known, inflammation may mediate the process.

In fact, he reported, “I am currently examining the relationships between multiple negative emotions and inflammatory markers relevant to cardiovascular disease such as the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 and the acute phase reactant C-reactive protein.”

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Pittsburgh Mind-Body Center.

An abstract of “Negative Emotions and Three-Year Progression of Subclinical Atherosclerosis” is posted at<http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/64/2/225>.▪