Search Is On to Discover 'Perfect' Pain Killer

David Daniels, Ph.D., a synthetic chemist at the University of Minnesota, says he has a lofty dream. “I want to develop the perfect analgesic”—that is, a drug that relieves pain, but that will not cause tolerance or dependence.

He announced his quest at a recent conference titled “Pain, Opioids, and Addiction: An Urgent Problem for Doctors and Patients.” It was cosponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the AMA.

The conference was also the perfect setting for Daniels' announcement since Nora Volkow, M.D., director of NIDA, had brought scientists on both sides of the divide—pain control and addiction— together. “For many years, the two fields did not talk with each other,” she said.

But until Daniels' perfect analgesic, or at least until safer analgesics than the current opioids, are developed, physicians using opioids to treat pain are faced with a tough balancing act, conference speakers stressed—relieving patients' pain while avoiding opioid tolerance or dependence.

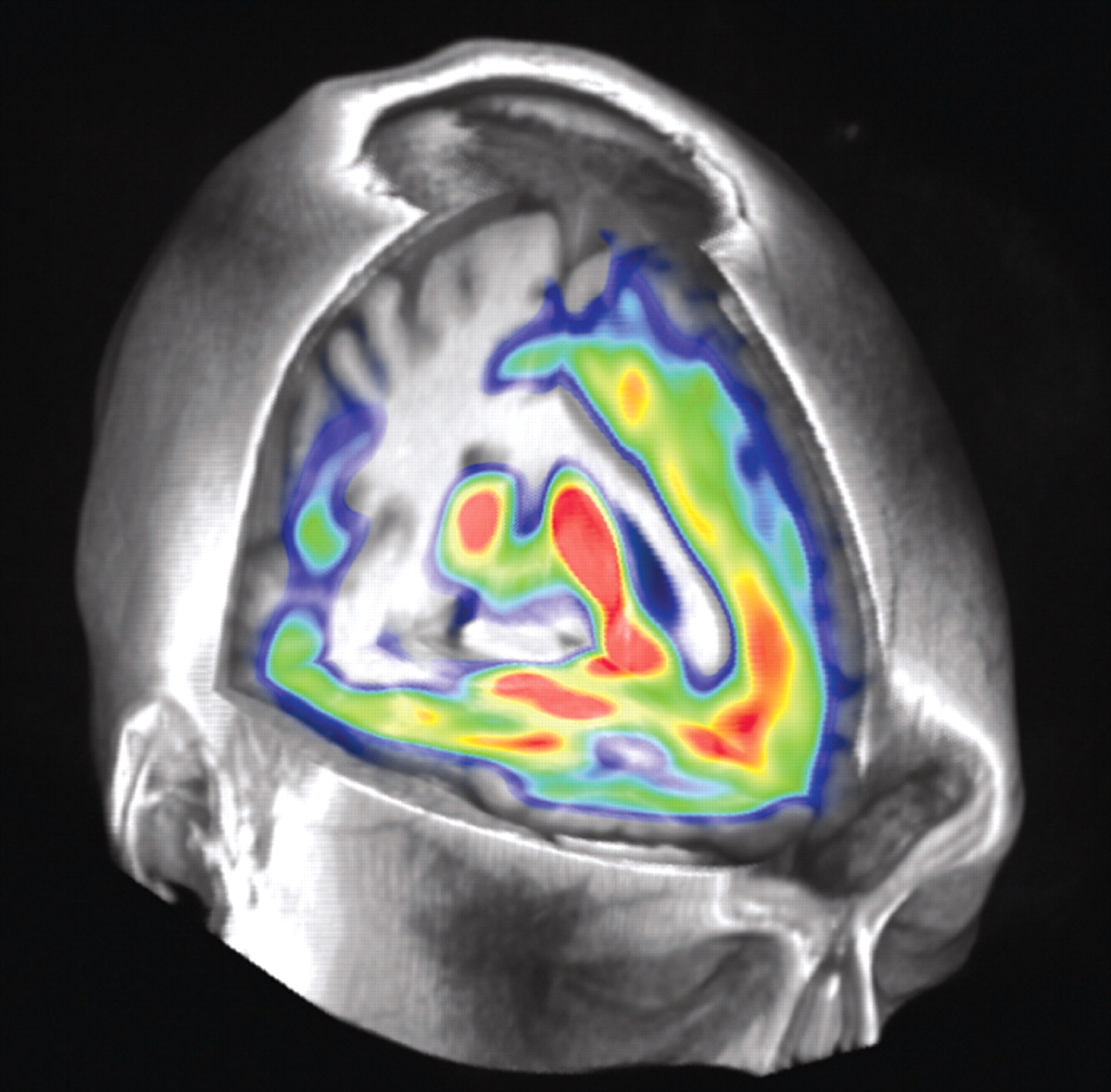

This neuroimage shows where mu opioid receptors are located in the brain. Opioid drugs produce their analgesic effects by acting on these receptors, among others. Some scientists have also developed a series of potent opioid analgesics that target complexes of the mu receptors and delta opioid receptors, but that do not produce tolerance and dependence as the currently available opioids can.

Credit: Jon-Kar Zubieta, M.D., Ph.D.

At first glance, the opioid analgesics seem to be wonder drugs, Nathaniel Katz, M.D., an adjunct assistant professor in analgesic research at Tufts University, reported. Some 30 randomized, placebo-controlled trials have found that they can counter numerous types of pain, but patients may develop tolerance to them. Yet virtually no research has explored this putative danger, Katz pointed out. So if patients ask whether an opioid is going to lose its pain-relieving effects over time, physicians should reply that they honestly don't know, he advised.

Risk Estimates Vary Widely

Even if the opioids relieve patients' pain without tolerance developing, there is the risk of dependence on them. However, only two prospective studies have been published that attempted to determine the magnit ude of dependence risk in an opioid-analgesic-using population, Katz said. And the studies came up with markedly different answers—2.5 percent to 5 percent in one and 32 percent in another.

The study that found a 2.5 percent to 5 percent opioid-dependence risk, Katz explained, was based on a very large sample size (more than 11,000 patients taking opioids for pain), but the diagnosis of opioid dependence was based on a nonvalidated, telephone survey, “so this is possibly why the estimate may have been on the low side,” he said.

The study that found a 32 percent risk, he noted, was a carefully designed prospective clinical trial in which patients were followed with urine toxicology, checked for doctor shopping, and other outcome measures. The reason why its opioid-dependence risk estimate was much higher than that of the other study, he speculated, may have been because of its excellent follow-up or because the “patients may have been at high risk to begin with, or otherwise they would not have been referred to the clinic in which the study was being done.”

In any event, yet a third prospective investigation to determine the degree of opioid abuse/dependence was reported at the pain-opioid conference by Mark Sullivan, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington. Its estimate of opioid-dependence risk was 2 percent, that is, close to what one of the two previous investigations found. But like the two previous studies, it too had its strengths and weaknesses, Sullivan pointed out. For example, it was based on a very large sample size (15,000 veterans taking opioid medications for pain relief), but automated diagnostic records were used to assess opioid abuse/dependence, so some cases may have been missed.

Some Risk Factors Identified

But even if the risk of opioid dependence is as low as 2 percent, physicians may worry that their patients might be among that percentage, conference speakers said. One possible red flag is depression, Sullivan indicated. In their prospective study of veterans, he said, “a diagnosis of depression while receiving opioid therapy predicted opioid dependence even when possibly confounding factors were taken into consideration.”

Another predictor of dependence is euphoria, Katz pointed out. In an unpublished study of 40 subjects taking opioids for pain, he and his coworkers found that those who initially experienced euphoria went on to become addicted.

So Daniels' dream—an opioid that relieves pain without causing tolerance or dependence—would indeed be a windfall for pain patients and the physicians who treat them. But how realistic is it?

Actually quite realistic, Daniels believes. He and his colleagues have developed a series of potent opioid analgesics that target complexes of mu opioid receptors and delta opioid receptors (two of the three types of opioid receptors identified to date). Several of these compounds do not produce tolerance or dependence. The University of Minnesota is in the process of patenting them, and two drug companies have approached the university about developing them.

Yet another approach to creating an opioid that relieves pain without producing dependence is being explored by Christopher Evans, Ph.D., a professor at the University of California at Los Angeles's Center for Study of Opioid Receptors and Drugs of Abuse. The tactic consists of separating the rewarding effects of opioids from their analgesic effects. For example, he is interested in combining opioid analgesics with antagonists of the cannabinoid system, which seems to be involved in the rewarding aspects of opioids.

In fact, new types of pain medications that are just as potent as the opioids and without the danger of dependence may become available during the next few years. For example, Ze'ev Seltzer, D.M.D., a scientist at the University of Toronto's Center for the Study of Pain, and his colleagues have amassed evidence that pain in both animals and humans has a strong genetic basis and have identified one of the genes involved. By 2010, he predicted, he and others in the field of pain genetics will have identified a number of important pain genes, and this identification will lead to the design of painkillers that are as effective as, but safer than, currently available opioids.

Nonmedical pain treatments, and thus purportedly without dependence problems, are being explored as well. R. Christopher deCharms, Ph.D., chief executive officer of Omneuron Inc. in Menlo Park, Calif., and his colleagues are using neuroimaging to train subjects to activate certain areas of their brains that are involved in suppressing pain. This activation, they hope, will then lead to pain relief. Results in a small number of patients suggest that such brain control is feasible and that it can counter both experimental pain and chronic pain over the short term.

“We are now doing studies to see whether [with this method] we can reduce chronic pain long term,” he said. “We have [studied] 21 patients to date. We are seeing a decrease in pain ratings thus far. But we do not yet have a placebo group in place.” ▪