Quality of Foster Care May Determine Future Mental Health

Childhood abuse and neglect can have a pernicious impact on mental health later in life, a large volume of research has found. Moreover, a high rate of child abuse and neglect in the United States has contributed, in part, to the large number of youth in foster care.

Yet investigators do not appear to have conducted a controlled study on the impact of foster care on the long-term mental health of abused or neglected youngsters, Ronald Kessler, Ph.D., a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, and his colleagues found. So they decided to take on the challenge themselves. (Kessler also headed the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, which was published in 2005.)

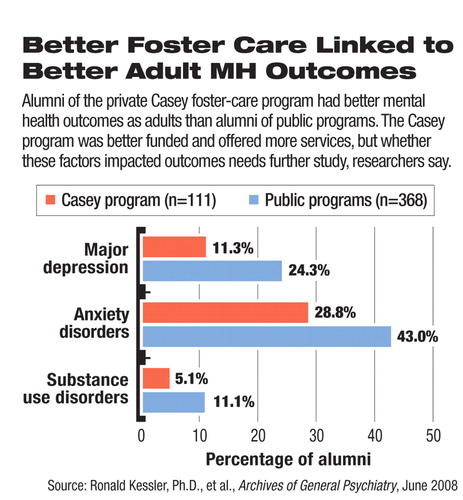

They compared the mental health outcomes of 368 adults who had received care as adolescents in two public-sector foster-care programs with the outcomes of 111 adults who had received care as adolescents in a private foster-care program called the Casey program. All subjects had been placed in foster care primarily because of maltreatment, and all had been out of care from one to 13 years at the time of the study.

The Casey program had provided not only more highly trained personnel and more intense services than the public programs, but also additional funds to foster parents and even postsecondary job training or a full college education to all participants. Turnover of foster parents and case-workers had also been substantially lower in the Casey program than in the public ones, resulting in more stability for participants.

Not unexpectedly, the Casey alumni seemed to have better mental health than public-program alumni. Specifically, in the year prior to the study, the Casey alumni had experienced significantly less anxiety, significantly less major depression, and significantly fewer substance-use disorders than the public-program alumni. Casey alumni also seemed to have better physical health—they had experienced significantly fewer ulcers and significantly less diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease.

“Public-sector investment in higher-quality foster-care services could substantially improve the long-term mental and physical health of foster-care alumni,” Kessler and his team reported in the June Archives of General Psychiatry.

However, before states invest in a Casey-model foster-care program, the investigators cautioned, more analysis is needed “because we are not sure that all of the more costly elements of the Casey package of services contribute[d] to the greater effectiveness of the Casey program.”

Also, states might want to include cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in a model foster-care program, the investigators proposed, since “CBT designed specifically to treat the emotional scars of child abuse and trauma” was not available in the Casey program, but has since been developed. And states should also explore other private foster-care programs besides the Casey one before deciding on a model foster-care program, the researchers advised, since there are many throughout the United States.

In an accompanying editorial, Charles Nemeroff, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Emory University, also made a novel suggestion—that researchers should examine whether optimal foster care can improve the mental health of maltreated youngsters who possess the SS variant of the serotonin gene. Past research has shown that the SS variant, when combined with child abuse, confers a particularly heightened vulnerability to depression, but psychosocial support can reduce the risk.

The study was funded by an unrestricted grant from the Casey Family Programs as well as by the states of Oregon and Washington, which is where the foster-care programs that were studied were located.

An abstract of “Effects of Enhanced Foster Care on the Long-Term Physical and Mental Health of Foster Care Alumni” is posted at http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/65/6/625.▪