Quality, Access to Care Heading in Wrong Direction

Amid recent reports that life expectancy is falling in some parts of the nation for the first time in decades, new research concludes that overall the U.S. health care system fell short of benchmarks set in a similar report two years earlier.

The “National Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance, 2008,” a compilation of health care statistics mostly from 2007, was published by the Commonwealth Fund, a nonpartisan, health-focused think tank. The scorecard aims to provide a comprehensive measure of U.S. health outcomes, quality, access, efficiency, and equity.

Compared with the findings of the first report, released in 2006, findings in the current report indicated worsening scores in the ability of the U.S. health system to provide healthy lives, quality care, or access to care. The scores for efficiency and equity improved slightly.

“The scorecard makes a compelling case for change” in health care policy, said Cathy Schoen, senior vice president of the Commonwealth Fund.

Among the greatest concerns was that access to care had significantly declined, as shown in the finding that more than 75 million adults—42 percent of all adults aged 19 to 64—were underinsured or uninsured in 2007. That was an increase from 35 percent of adults in that age range in 2003.

One impact of the health insurance disparities was on quality of life: there was a greater percentage of uninsured working-age adults who were limited in activities because of “physical, mental, or emotional problems,” compared with insured adults.

The report also stated that the U.S. system had failed to keep pace with the health gains in other advanced countries. The U.S. ranking fell from 15 to 19 in “mortality amenable to medical care” among the 19 countries tracked in the report.

Among the health care areas in which the report identified a need for improvement is access to quality mental health care. The report noted that among adults who have major depressive illness, for example, many remain untreated. Although the rate of treatment for people who have depression improved from 65 percent to 69 percent on the current scorecard, that still left nearly 1 in 3 such individuals without any care.

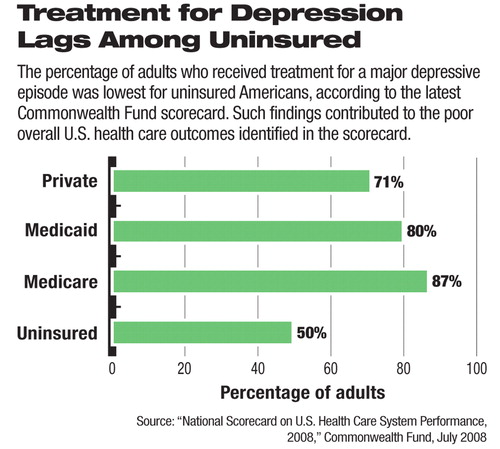

The researchers found that the percentage of adults who received care for a major depressive episode was greatest among Medicare, military, and veterans health beneficiaries—87 percent—and lowest among the uninsured—50 percent. The researchers found as well that about 71 percent of people with private insurance who needed depression treatment received it, as did 80 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries.

“Mental health indicators tell us this is an area where we need to improve in the United States,” Schoen told Psychiatric News.

The scorecard noted that additional gaps in mental health care are created by the provision of inadequate mental health care, which the report defined as care that is not effective, well-coordinated, safe, timely, and patient centered. Improvements in mental health care would benefit not only those with mental illness but overall society as well. Improving depression care alone would increase workplace productivity by an estimated $2.2 billion annually, the researchers estimated.

Schoen said that health care research consistently indicates a reliance on crisis care to treat serious mental illness. After the crisis is resolved, patients are frequently discharged with no follow-up care. This leaves providers and patients “waiting for another crisis,” Schoen said.

The U.S. system could benefit from a move away from crisis mental health management and toward systematic preventative care, which is much more prevalent in other advanced countries.

For children's health, U.S. primary care providers tend to focus almost exclusively on children's physical health and ignore mental health problems that often have a serious impact on their overall health, according to the report.

Only 59 percent of children who needed mental health care received it in 2003, the last year for which data were available, the researchers found. The rate of treatment for mental illness ranged from 63 percent for children with any type of health insurance to only 34 percent for children not covered by insurance.

The scorecard is the latest research to highlight the need for changes to improve health care outcomes for Americans, said Carolyn Clancy, director of the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, during discussion in July before congressional staff regarding the scorecard. The findings illustrate that the biggest potential for savings can come from better care of chronic conditions, for example, in the 20 percent of Medicare beneficiaries who incur 72 percent of the program's treatment costs.

In the short term, however, “under the current financing system all of the players lose money [if chronic care were to be improved], so there is no incentive for change,” Clancy said.

The scorecard's authors called for “bold leadership and commitment” to pursue a whole-system approach that would improve access, quality, and efficiency simultaneously. The specific steps to improving care would include a universal and well-designed coverage plan that would allow affordable access and continuity of care with low administrative expenses. Such a system would need to be organized around the patient and not around providers or insurers, as is the case in the current system.

“To secure a healthy nation, we need to come together around plans and policies that can improve health outcomes,” Schoen emphasized.

The “National Scorecard on U.S. Health System Performance, 2008” is posted at<www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/publications_show.htm?doc_id=692682>.▪