Several Reasons Keep Clinicians From Reporting Child Abuse

Primary care clinicians do not report about one 1 in 4 cases of suspected physical child abuse, because they either distrust local child protective services or think they can intervene more effectively by other means, according to studies published in the August and September Pediatrics.

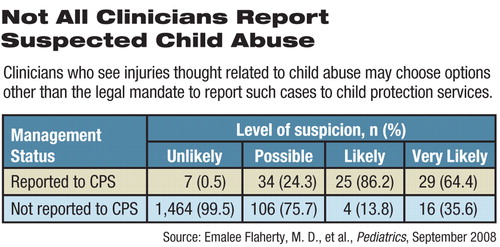

Of the 15,003 child-injury visits included in the study, 1,683 raised suspicion of physical abuse, yet the clinicians reported to child-protection authorities only 73 percent of the children they thought were“ likely” or “very likely” to have been abused; only 24 percent reported those they thought had “possibly” been abused. The rest were not reported (see table below).

“Clearly, factors other than levels of suspicion play a role in clinicians' decision to report,” wrote Emalee Flaherty, M.D., and colleagues of the Child Abuse Reporting Study (CARES). The patient's medical and family history and physical examination findings, injury characteristics, and the clinician's previous reporting experience also affected their decision.

“The 27 percent of clinicians who did not report is a very conservative number, and in fact a larger percentage of clinicians may not have reported very suspicious injuries,” said Flaherty in an interview with Psychiatric News.

The 327 clinicians (88 percent were physicians, and most of those were pediatricians) whose data were included in the CARES study were members of the American Academy of Pediatrics Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network or the National Medical Association Pediatric Research Network. Data were collected from October 2002 to April 2005.

The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, and the American Academy of Pediatrics funded the studies.

A second, related study based on interviews with a subsample of clinicians delved into their reasoning about decisions to report suspected child abuse. Those who did not report often cited worries that child protective services (CPS) agencies would not investigate a report or would not supply ongoing information on a case, wrote Risé Jones, Ph.D., and her colleagues (including Flaherty). Those who reported were more likely to consult with other professionals in making their decision.

“The pediatricians were pretty brave to take on this issue,” said Sandra Kaplan, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine and director of the Division of Trauma Psychiatry at North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System, in an interview. She commended the American Academy of Pediatrics for addressing the problem of underreporting child abuse and suggesting steps to overcome it.

When More Likely to Report

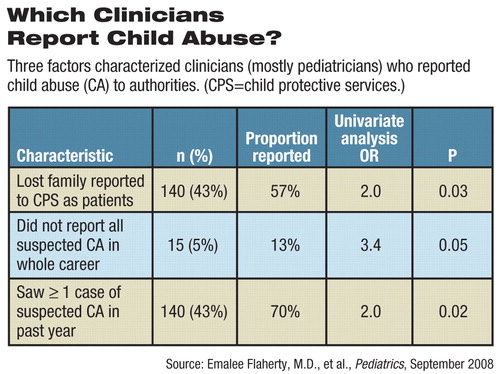

Clinicians were more likely to report if the injury was inconsistent with the patient's history or if the patient was referred because of suspected abuse.

They were also more likely to report suspected abuse to CPS if they had ever lost patients after reporting or if they had not previously reported all suspected child abuse.

That may seem contradictory, but perhaps more experienced clinicians feel more confident about reporting or not reporting and may manage some suspected abuse on their own, suggested the authors.

Some doctors fear they will lose patients if they report child abuse. But, said Flaherty, “Most families stay with their doctor even after he or she reports suspected child abuse. For one thing, the perpetrator may not be a member of the immediate family.”

There were no racial differences in reporting rates of patients without private health insurance. However, among privately insured children, injuries to black children were reported at a higher rate.

“We think this is not because the black children were over-reported, but because the injuries to the non-black children were underreported,” Flaherty speculated.

“We don't know why this should be,” she said. “The pattern has shown up in other studies, and we will be looking more closely at our data to try to understand it.”

Severe injuries were more likely to be reported. That may seem obvious, but the researchers noted that clinicians may be reluctant to report less-serious injuries because they found that CPS was less likely to confirm them. However, limiting reporting to severe injuries may lessen the chances of receiving services by children who are repeatedly abused with “minor” injuries, which may also lead to long-lasting emotional and developmental harm, they said.

Reporting Factors Identified

In detailed follow-up interviews of 75 clinicians, Jones and colleagues identified influences on the decision to report.

“As in most medical decisions, clinicians weigh the likely costs and benefits of reporting a case and apply the lessons learned from previous experience,” they wrote.

Most clinicians who reported injuries said they had little familiarity with the family, while clinicians with a high suspicion of child abuse who did not report injuries frequently said that familiarity with the family led them to their decision. Others said that knowledge of family stressors or prior red flags about the family increased the chance of reporting.

Seeking outside advice appeared to help tip the balance toward reporting. About 82 percent of those who reported discussed their suspicions with colleagues first, while just 18 percent of those not reporting did so.

Those who did not report said they assumed responsibility for patient follow-up, referred patients to other medical or social services, or would look for further injury in a return visit before reporting.

Disconnect Hinders Reporting

The disconnection between the medical and the child-protection worlds serves to hinder full reporting, said consultant John Goad, M.A., a former director of child protective services in Illinois, in an online supplement to the research articles. On one hand, many doctors distrust CPS and believe such agencies will not protect the child. They have seen CPS apparently fail to pursue reported cases and fail to provide feedback to physicians. Doctors grumble about the need to take an uncompensated day from work if they need to testify in court.

For their part, CPS workers may complain that doctors don't provide enough information to conduct a proper investigation or that physicians want to encroach on their turf. CPS agencies, like most government social-service agencies, are under-staffed and underfunded.

Several approaches may improve the reporting system and its outcomes. Better education for clinicians about child abuse on every level would be a good start.

“There have to be changes in medical education,” said Kaplan.“ Child abuse is taught, briefly, in the preclinical years, but it should be addressed in the clinical years of medical education and residency because experience is needed to develop competency.”

Studies of the effectiveness of continuing medical education programs about child abuse are few and have produced equivocal results.

Developing team approaches to identifying injuries reportable as child abuse might improve understanding of what each professional group can do and lead to better cooperation and better results for the children.

“Rather than a response that combines the expertise of all involved, there are multiple, parallel, but often uncoordinated efforts,” said Goad. Establishing interdisciplinary child-protection committees at the medical-center or community levels would help break down barriers, said several of the authors.

Flaherty now works with a group in Chicago comprising CPS workers, law-enforcement personnel, and medical practitioners from three city hospitals to sort out difficult cases of potential child abuse. The team approach can also provide expert consultation for primary care physicians, an advantage, given that doctors who consult are also more likely to report.

“I see the benefits, but I also see that it's not easy to get it to work,” she said. Simply scheduling group members to meet in the same room at the same time can be difficult. Ultimately, the life and safety of the child are the touchstones for action.

“You don't have to be certain that a child was abused, just see a 'reasonable likelihood' of abuse,” said Flaherty. “If you wait until you are certain and have eliminated all other possibilities, it may be too late for the child. You have to keep the child safe while investigating other possibilities.”

“From Suspicion of Physical Child Abuse to Reporting: Primary Care Clinician Decision-Making” is posted at<http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/peds.2007-2311v1>. Other articles in the series are posted at<http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/papbyrecent.shtml>.▪