Depression-Onset Timing Key After Heart Attack

“Renee,” a Washington, D.C. career woman, took an early retirement after she had a heart attack. Many 60-year-olds would have reveled in such “freedom,” but Renee did not. Renee (not her real name), some of her neighbors suspected, was depressed by her new situation. But then a few weeks later, Renee had another heart attack while in her apartment and called 911. By the time the paramedics broke down her door, she was dead.

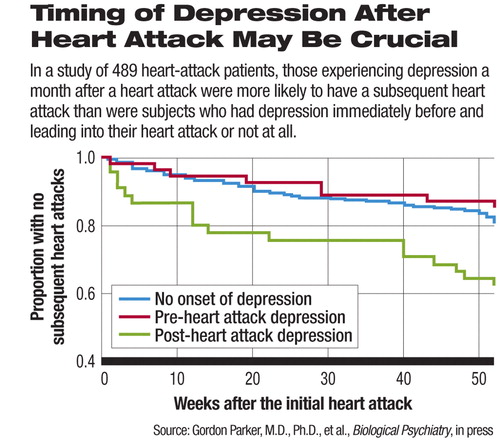

Was there a link between Renee's post-heart-attack depression and her subsequent death from another heart attack? A new study suggests that there could be. It found that when heart-attack patients become depressed a month after having their attack, they are seven times more likely to have another attack than are heart-attack patients who do not become depressed at this time.

A spate of studies have already demonstrated that people who have a heart attack and who have experienced depression at some point in their lives have a worse coronary outcome than do people who have a heart attack and who have never been depressed. Moreover, numerous studies have linked depression around the time of a heart attack with a poor outcome from that attack. But what has been unclear is when a depression has to occur in order to pose such risks. So Gordon Parker, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of New South Wales in Australia, and his coworkers decided to conduct a study to answer this question.

They recruited 489 hospitalized heart-attack patients to participate in their study. The subjects were assessed, on average four days after their admission, for lifetime and current depression by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview depression schedule. Out of the 489 subjects, 38 were found to have experienced a depression at some point earlier in their lives, and 12 percent were found to be currently depressed—that is, to have been depressed right before and right after their heart attacks.

A month after the baseline interview, that is, after the subjects had been discharged from the hospital and were back home, they were contacted by telephone, and a DSM-IV depression symptom checklist was used to determine how many who had not been depressed while in the hospital were depressed at this time point. Ten percent were.

All subjects were followed up during the next 11 months to determine whether they experienced any more heart attacks. The researchers looked to see whether depression at any time point could be linked with a subsequent heart attack. And during their analyses, they considered such potentially confounding factors as age, gender, cardiac risk factors, antidepressant use, and current smoking status.

The researchers could find no significant link between depression earlier in life and a subsequent heart attack. Nor could they find any significant link between depression right before and after a heart attack and a subsequent heart attack. But they could find a significant link between depression that appeared a month after a heart attack and a subsequent heart attack.

In fact, the chances of having a subsequent heart attack were seven times greater for those heart-attack subjects who were found to be depressed a month later than for subjects who did not become depressed at this time. In contrast, recognized cardiac-risk factors such as clogged arteries, stroke, or diabetes posed considerably lower risks in this regard, the researchers found.

These findings have some practical implications, Parker and his team concluded in their study report, which is in press with Biological Psychiatry. “We suggest that close attention should be paid to how patients' mood states progress beyond hospitalization.”

The findings may also shed light on why depression occurring a month after a heart attack so often heralds another heart attack. Preliminary research that Parker and his colleagues have conducted suggests that a depression that occurs at this time has a biological rather than a psychological origin. And as they noted in their study report, this biologically triggered depression“ may actually be a signal marker” that something has gone wrong in the body and have nothing to do directly with causing a heart attack. For instance, the depression could be a signal that the heart's involuntary nervous system has started to malfunction.

Indeed, some other researchers have found that depressed heart-attack patients exhibit dysfunction of the heart's involuntary nervous system and that such dysfunction in turn can increase a person's chances of dying from a second heart attack.

The study was funded by Australia's National Health and Medical Research Council Program and the New South Wales Department of Health.

An abstract of “Timing Is Everything: The Onset of Depression and Acute Coronary Syndrome Outcome” can be accessed at<www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps> by clicking on “Articles in Press.” ▪