Role of Prenatal Stress Studied in Schizophrenia

Studies tying large health databases with disease registries continue to provide evidence for the association of stresses during pregnancy and the occurrence of psychiatric disorders among affected offspring, but the low prevalence of those disorders, even in studies based on large populations, still leaves room for uncertainty.

“Aberrations in fetal experience in a subset of persons, whether caused by stress, infections, or famine, alter the neurodevelopment of the fetus,” explained epidemiologist and developmental psychologist Stephen Buka, Sc.D., a professor of community health at Brown University Medical School. “That should be considered established.”

“When you connect what we know about neuroanatomy with the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, it seems quite logical and is supported by the evidence that some portion of those brain abnormalities in adults have their origins early in fetal development,” said Buka.

Recent studies illuminate both the promise and the pitfalls of such research.

The results of a pilot study linked a short-lived, prenatal societal stressor with incidence of schizophrenia. In it, U.S. and Israeli researchers compared data from the Jerusalem Perinatal Cohort Study with records in Israel's national Psychiatric Registry covering all admissions to psychiatric wards and day-treatment facilities in the country.

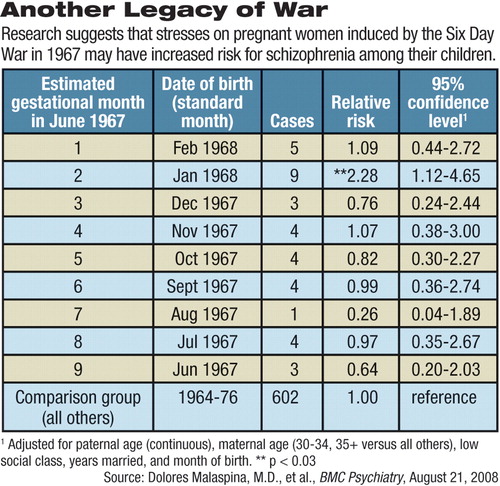

Dolores Malaspina, M.D., M.P.H., Susan Harlap, M.B.B.S., both professors of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine, and colleagues investigated whether women who were pregnant at the time of the Arab-Israeli war in June 1967 were more likely to give birth to children who later were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

They found no differences when analyzing results by trimester, but did see a significant increase in schizophrenia-related diagnoses among children born in January 1968, corresponding to a gestational age of two months in June 1967.

“[A] time-limited threat likely to have caused severe anxiety in pregnant women was associated with an altered incidence of schizophrenia in the offspring,” wrote Malaspina and colleagues in the online, open-access journal BMC Psychiatry on August 21.

They also found that a disproportionate number of girls developed the disorder. The sex difference may be due to increased vulnerability to stress or to a greater mortality of vulnerable males, they suggested.

They traced 88,829 offspring included in the Jerusalem Perinatal Cohort, which covered births from 1964 to 1976 in western (Israeli) Jerusalem. Overall, 637 of the children developed schizophrenia, and 676 developed other psychiatric disorders by age 30. The stressor faced by the mothers was the three-week period leading up to and including the war, from May 18, 1967, to June 11, 1967.

They found that nine of the 493 births in January 1968 (based on standard month of birth) eventually were diagnosed with schizophrenia or related illnesses, compared with two to five births in the previous and following two months. Although absolute numbers were low, the differences were statistically significant, the researchers said.

However, other factors might have affected these results, pointing out problems common to this research field, said Buka, who was not involved with the Jerusalem study.

“The definition used of schizophrenia included not only schizophrenia but also schizotypal disorder, delusional disorders, nonaffective psychoses, and schizoaffective disorder,” he pointed out. In addition, if the estimated gestational age was off and the babies were born prematurely, they might well have been conceived in June 1967 by parents who were not mobilized for war, either for reasons of age or poor health, he said.

Malaspina and Harlap were careful not to overinterpret their findings.

“[O]ur results should be regarded as 'hypothesis generating' rather than proof that the greatest vulnerability to schizophrenia occurs in the second, rather than any other, gestational month,” they said.

The first trimester of fetal development has received the most attention because that is when most organogenesis happens, especially in the brain, said Katherine Abel, Ph.D., of the Centre for Women's Mental Health Research at the University of Manchester in England, in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Researchers must be cautious about attributing population-wide stressors to individuals, she said. Abel and several colleagues published a study of the effects of antenatal stress on risk of schizophrenia in the February Archives of General Psychiatry.

They studied a cohort of 1.38 million births recorded in Denmark's Medical Birth Registry from 1973 to 1995. They found a slight increase (1.67) in adjusted relative risk among mothers exposed to the death of a first-degree relative in the first trimester of pregnancy.

That study ties the exposure to a stressor specific to the individual woman, said Abel. War or famine may affect people differently, depending on any number of intermediary factors, such as socioeconomic status, she said. Furthermore, many genetic, behavioral, and environmental effects probably combine to cause what, in the end, is a fairly rare event.

Abel is now involved in an even larger study based on health registries in Sweden and hopes that the larger size and increased power will provide better data on gender and timing of prenatal influences on the origins of schizophrenia.

While conclusive research tying psychiatric epidemiology to developmental stages remains in the future, some practical lessons can be drawn from the current state of knowledge, said Buka and Abel.

“Women's condition in pregnancy has an important effect on outcomes, so holistic care of pregnant women is important,” said Abel.

“We should enhance the pregnancies of women at high risk because of environmental stressors or family history by intervening to reduce stress, ensuring that they have a good diet, and checking frequently for infection—especially in the first trimester,” agreed Buka.

“Acute Maternal Stress in Pregnancy and Schizophrenia in Offspring: A Cohort Prospective Study” is posted at<www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-244x-8-71.pdf>.▪