Depressive Phases Cause Most Distress for Bipolar Patients' Caregivers

A lot of persons with bipolar illness have their illness well controlled with medications or rarely experience symptoms. Others, however, do not, imposing stress on their families or caregivers.

But what is the most troubling aspect of living with a bipolar patient? The patient's ups or downs? It turns out that it's the downs, a new study has found.

It was headed by Michael Ostacher, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Results were published online on June 28 in Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica.

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study has already provided a wealth of information on how to help bipolar patients (Psychiatric News, March 3, 2006; May 4, 2007; September 21, 2007). This study “piggybacked” on the STEP-BD investigation. A total of 500 bipolar patients participating in the original STEP-BD investigation, as well as their 500 primary caregivers, agreed to participate.

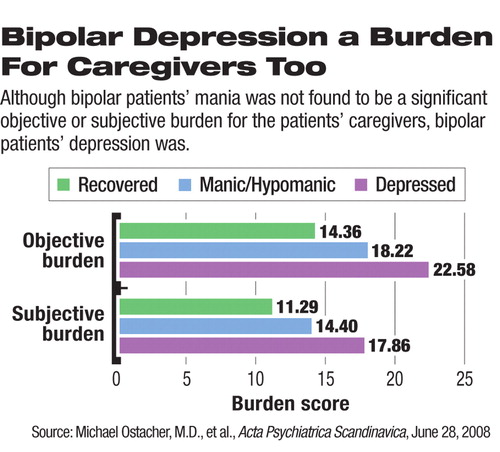

The patients' moods were charted over a year. During this time, information was also collected about the caregivers'“ objective” and “subjective” burdens of caring for a bipolar patient.

Objective burden constituted the number of stressors a caregiver experienced—say, problematic patient behaviors, patient social dysfunction, or adverse effects of the patient's illness on the caregiver's work and leisure time.

Subjective burden was the degree of distress a caregiver experienced as a result of each stressor. Finally, Ostacher and his team looked to see whether there were links between patients' moods at particular periods and caregivers' burdens at the same periods.

No significant links were found between caregivers' objective or subjective burdens and patients' manic phases. However, highly significant links were found between caregivers' objective or subjective burdens and patients' depressive phases.

These findings surprised him, Ostacher told Psychiatric News, but“ in retrospect it makes sense since [bipolar] depression is often chronic and debilitating, while mania is dramatic, but short-lived.”

So just as past research has revealed that depression, not mania, seems to be bipolar patients' greater nemesis, the same seems to be the case for their caregivers, Ostacher and his colleagues concluded.

The take-home message is that clinicians treating bipolar patients should initiate “maximally effective treatment” for the patients' depression, both for the patients' sake and that of their caregivers, the researchers said.

This maximally effective treatment, Ostacher told Psychiatric News, should include structured psychotherapies that are effective for bipolar depression, as well as family-focused treatment that includes caregivers.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

An abstract of “Correlates of Subjective and Objective Burden Among Caregivers of Patients With Bipolar Disorder” is posted at<www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/120082192/abstract>.▪