Misdiagnoses Common in Cases of Depression With Psychosis

The diagnosis of major depression with psychotic features is often missed in patients, especially in the emergency room, a study reported in the August Journal of Clinical Psychiatry pointed out.

The study, which was headed by Anthony Rothschild, M.D., chair of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts, included 65 inpatients at four academic medical centers. Subjects were recruited from a larger study called the National Institute of Mental Health Study of Pharmacotherapy of Psychotic Depression (STOP-PD), and STOP-PD researchers had determined that all of them had psychotic depression.

Moreover, to be in their study, Rothschild explained to Psychiatric News, “all subjects were required to have at least one delusion, and some also had hallucinations. The delusions were most typically somatic delusions, paranoid delusions, delusions of guilt, delusions of poverty, and nihilistic delusions that bad things are about to happen.”

Rothschild and his colleagues then gathered each patient's hospital records from the time preceding their enrollment in the STOP-PD study to see what types of diagnoses he or she had received in the hospital emergency room or hospital psychiatric unit. The 65 inpatients had received, altogether, 130 diagnoses, meaning that some had received several diagnoses. Finally Rothschild and his team looked to see whether these 130 diagnoses had been made correctly.

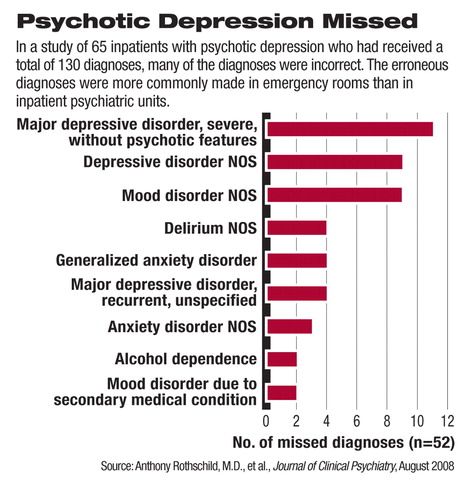

Over one-fourth had not, the researchers found. The three most common misdiagnoses were major depressive disorder without psychotic features, depression not otherwise specified, and mood disorder not otherwise specified. Misdiagnoses made less often included delirium, anxiety disorder not otherwise specified, and alcohol dependence.

The erroneous diagnoses were more common in emergency rooms than on inpatient psychiatric units, and as Rothschild and his colleagues pointed out,“ It is quite striking that none of the patients with missed diagnoses were considered to have a psychotic disorder. This finding suggests that the physicians are missing the psychosis rather than the mood disorder. In many cases, it may be that the physician does not miss the symptom (for example, guilt, poverty, persecution), but does not recognize that the symptom is a delusion. In particular, the distinction between delusional and nondelusional guilt is frequently difficult.”

These findings have important clinical implications, the researchers believe, since major depression with psychotic features often entails considerable morbidity and mortality, and its treatment differs from that for major depression alone. According to the APA 2000 practice guideline on the disorder, either an antipsychotic with an antidepressant or electroconvulsive therapy should be used, they noted.

“As the process for DSM-V is beginning,” they continued, “it will be important to revisit the issue of whether 'major depression with psychotic features' should be a separate illness in DSM-V, as was recommended (but rejected) for DSM-IV, rather than a specifier of 'major depressive disorder,' a position where it can more easily be overlooked. The hope would be that if 'major depression with psychotic features' were a separate illness in DSM-V, it would result in greater awareness and more accurate diagnosis among practitioners.”

Meanwhile, Rothschild offered the following tips on how psychiatrists can better detect psychotic depression:

Develop a therapeutic relationship with patients so that they feel comfortable confiding their thoughts to you. | |||||

Since patients are often guarded, use nonthreatening terms such as“ irrational worries” instead of “paranoia” or“ psychosis.” | |||||

Listen carefully for clues of psychosis—for example, a patient saying something such as “My thoughts are not quite right.” | |||||

Involve family members in the assessment process of the patient. They may have observed strange behavior or speech that might indicate psychosis. | |||||

Also, Rothschild has written a book, Clinical Manual for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Psychotic Depression, to help physicians better diagnose the disorder. It will be available through American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. in November.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

An abstract of “Missed Diagnosis of Psychotic Depression at Four Academic Medical Centers” is posted at<www.psychiatrist.com/abstracts/200808/080813.htm>.▪