Psychiatry and All That Jazz Are Parallel Passions

One might say that Denny Zeitlin, M.D., got an early jump on his dual career as a psychiatrist and jazz pianist.

His father was a radiologist who learned to play piano by ear, and his mother was a classically trained pianist. He can remember at the age of 2 climbing up on their respective laps and placing his little hands on theirs as they played on the Steinway in the living room so that he could “get a sense of what it was like to traverse the keyboard before I could sit there myself and play,” he said in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Less than a year later, Zeitlin claimed the piano bench for himself and began creating melodies and improvising upon them.

The precocious boy from Highland Park, Ill., soon discovered that he possessed another gift.

“It wasn't too many years later that I began practicing psychotherapy on the playground, without a license,” Zeitlin remarked.

State licensing boards need not be alarmed, however. Zeitlin, inspired by his uncle, who was a psychoanalyst, was merely listening to his elementary-school classmates who had entrusted him with problems relating to parents, siblings, and peers.

“I wanted to listen, understand, and be helpful to them,” said Zeitlin, adding that he found the experience of guiding his peers through the pitfalls of their elementary-school years fascinating and gratifying.

He also voraciously read books with psychological theories or themes and was certain that he would eventually enter the helping profession.

Zeitlin received formal training first in music and then in medicine but never imagined that it would be impossible to have a successful career in both fields.

“The cross-pollination of music and psychiatry in my life has always been crucial to me,” he remarked.

Playing With the Pros

When at age 6 Zeitlin began studying classical piano, he found that he was drawn to the modern composers. During this period of formal study, he said, he was less interested in reinterpreting the written page note for note as classical pianists do and more interested in studying how the music was structured and transforming it to make his own.

One of the defining moments in his life came during the eighth grade, when he first heard a jazz album by George Shearing, which was markedly different from anything Zeitlin had experienced up to that point. “I could tell that new music was being composed from moment to moment, and I was blown away by the rhythmic drive of the music,” he said.

Zeitlin's discovery of jazz could not have come at a better place or time. Chicago in the early 1950s boasted a burgeoning jazz scene, and during his high-school years Zeitlin would sit in with jazz musicians at local clubs until the wee hours, an experience he called “an informal apprenticeship in the world of jazz.”

He also formed a jazz trio of his own, and would play with other ensembles as well at cocktail parties or local jazz venues.

As an undergraduate at the University of Illinois and then as a medical student at Johns Hopkins, Zeitlin continued to play with seasoned jazz musicians. “I can recall studying for six hours each night in my monastic cell in the medical resident hall,” Zeitlin said, “and then I'd drive to a local jazz club and sit in with some jazz musicians for several hours after that, just immersing myself in the music.”

Recording Career Is Launched

Although he was interested in honing his musical skills, in light of his medical studies he had no plans to begin a recording career or even to make his music more public. That all changed when as a third-year medical student in 1963, he was offered a fellowship in psychiatry at Columbia University in the New York State Psychiatric Institute. During his 10-week stint there, he met with famed Columbia Records producer John Hammond, who was enthusiastic about Zeitlin's work, and together they went to work in the studio.

His first recording was as the featured pianist on “Flute Fever,” an album by Jeremy Steig.

Between 1963 and 1967, four additional albums were released by Columbia, featuring the Denny Zeitlin Trio.

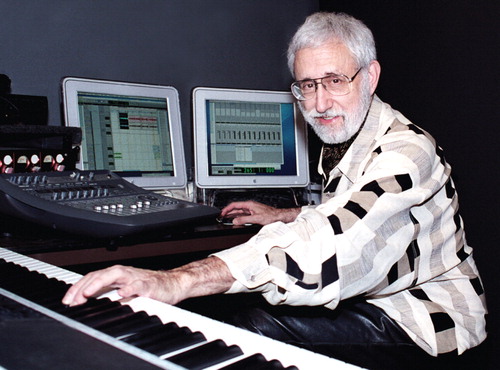

He has since released more than 30 recordings, maintained an international performing career, appeared frequently on network TV and radio, and twice won first place in the Down Beat International Jazz Critics Poll.

Zeitlin Trio, from left: Buster Williams, who plays bass; Denny Zeitlin, piano; and Matt Wilson, drums.

Credit: Josephine Zeitlin

His two most recent releases showcase the span of his work over the years. One is a three-CD box set reissue from the 1960s called, “Denny Zeitlin: The Columbia Studio Trio Sessions,” and the other is a CD featuring his current trio, titled, “Denny Zeitlin Trio in Concert Featuring Buster Williams and Matt Wilson.”

Reviews of Zeitlin's work are often infused with praise for his inventiveness—for instance, a review in the Los Angeles Times referred to him as an “artist whose skills are so expansive that he can integrate everything he hears into the fabric of his soloing. In the best sense, in the manner that has always been true of jazz's finest improvisers, Zeitlin constantly stretches the creative envelope, measuring himself only against the infinite demands of his music.”

Jazz historian Ted Gioia, looking back on Zeitlin's early work with Columbia Records, asked in one review, “And why is Denny Zeitlin important? There is the obvious matter of his formidable technical command of the instrument. His touch, his dynamics, and his clarity of execution are exemplary. But even more to the point, Zeitlin came to grips with virtually all of the pressing issues facing the jazz keyboardists of his generation.”

Zeitlin's musical career was not limited to studio recordings and concerts; he was asked to compose the musical score for the 1978 remake of“ Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” starring Donald Sutherland and Brooke Adams. He also composed and performed music for the first season of the TV show “Sesame Street.”

A Life Improvised

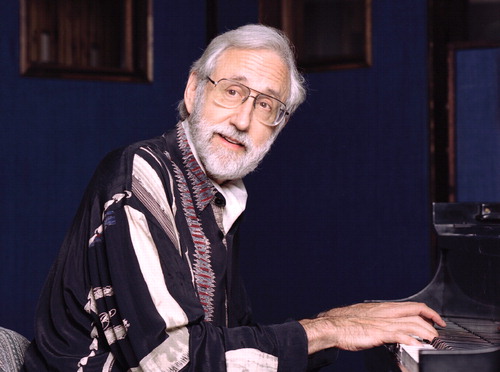

After graduating from medical school, Zeitlin moved to San Francisco in 1964 to intern at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), where he also completed a psychiatry residency in 1968 at the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute and where he is now a clinical professor of psychiatry.

In addition, he has maintained a private practice out of his home in Marin County and an office on the UCSF campus, where he conducts psychotherapy with individuals, couples, and groups. He also consults to other psychotherapists' practices and conducts courses and workshops in psychotherapy.

Zeitlin's longtime mentor was Joseph Weiss, M.D., a psychoanalyst and founder of control-mastery theory with whom Zeitlin met each week from 1975 until Weiss's death in 2004. Control-mastery theory is a psychodynamic, cognitive, relational theory about how pathogenic beliefs stem from early traumatic events; the goal of the therapy is to help patients change their pathogenic beliefs.

He has been able to find a common thread throughout his work with patients and his music through a workshop he has developed titled “Unlocking the Creative Impulse: The Psychology of Improvisation.”

Zeitlin has found in his work and life that the best way to unleash one's powers of creativity and to excel at creative or analytic pursuits is to blend the discipline of the craft—focusing on technical skill, for instance—with a more experiential approach in which one loses the“ positional sense of oneself” and becomes one with the activity.

When this state is achieved while playing music, Zeitlin noted, he feels as if he is simply a conduit for his music, and he experiences the music not just in sound, but in color and texture.

He finds that in his work with patients, this state is achieved when he is able, on an intellectual and emotional level, to enter his patients' worlds“ in the most deep and empathetic way so that I can more fully understand what it is that they are trying to describe.”

Though his work with patients and music are major components of his life, Zeitlin refers to his wife of 40 years, Josephine, as the “hub” of his life. She is a landscape designer and actor whom Zeitlin describes as“ the most naturally creative person I've ever known.”

At age 70 Zeitlin has no plans to slow down and is excited about the future. “I have created a body of work over the years that feels authentic to me. My goal is to keep growing as an artist and keep finding new ways to stretch myself as a musician,” he said, and the same holds true in his work as a psychiatrist: “I'm hoping to find new ways to be effective in my work with patients.”

More information about Denny Zeitlin and his work is posted at<www.dennyzeitlin.com>.▪