Psychiatrist Gains Otherworldly View of Mental Health

This is a tale of a “space junkie” who became a psychiatrist who became a space scientist.

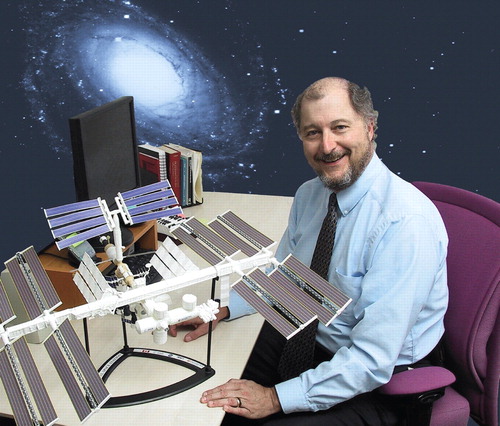

He is Nick Kanas, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

He is not only “having a ball,” as he puts it, but learning things of value to astronauts, mission-control personnel, and even psychiatry.

His destiny certainly didn't seem to be “written in the stars,” as they say. His father and his mother's parents immigrated from Greece, and neither of his parents had an interest in outer space. “But I was fascinated by outer space even when I was a child,” he told Psychiatric News. “I read a lot of science fiction, was an amateur astronomer when I was 11, and have always looked up to the sky.”

In fall 1970, during his last year in medical school at the University of California at Los Angeles, he arranged to take an elective at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston. There, he gathered information from submarines and Antarctic expeditions to infer what some of the psychosocial issues of a manned trip to Mars might be. He wrote up his findings and speculations in the form of a monograph. He arranged to do his medical internship at the University of Texas, Galveston, so that he would be near the Johnson Space Center and perhaps able to get his monograph published. The strategy worked: the National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA) published it in 1971. “But after it came out, I went on with my life. I thought about becoming an astronaut, but Americans were not flying much in space then.”

He did a psychiatry residency at the University of California, San Francisco, became a staff member in the department there, and pursued research on group therapy, especially for persons with schizophrenia.

In the early 1990s, in preparation for its involvement in the International Space Station, NASA became interested in the psychological and interpersonal aspects of space travel. Kanas and some colleagues sent a proposal to NASA to conduct such a study on Mir, the Russian space station. NASA agreed to fund it, and the Russians agreed to host it.

Since then, Kanas has conducted other psychosocial space studies for NASA, and with Russian as well as American colleagues.

Relations Were Amicable

He and his coworkers have obtained some interesting results. For example, they studied how American astronauts and Russian cosmonauts related to one another on the International Space Station during missions lasting up to seven months. They did not find any particular difficulties during that time.

“It may be because of the tremendous support that both the American and Russian mission-control staff offered their astronauts and cosmonauts,” said Kanas. “For example, if the astronauts or cosmonauts got blue or homesick, mission-control staff arranged to have their families talk with them or send them surprise packages via the next shuttle to the station.”

However, Kanas and his team did find that the astronauts experienced displacement. “When a group of people are under stress and can't talk about it, they may redirect their frustrations onto people outside the group,” Kanas explained. “That's displacement. And for the astronauts, they redirected their tension onto mission-control personnel.”

Kanas and his team likewise discovered some cultural differences between the American astronauts and the Russian cosmonauts. The Americans reported feeling more pressure at work. “It may be because the Americans perceived they had more work to do than the Russians did, or that the Americans actually had more work to do than the Russians did,” Kanas speculated.

Astronauts Said to Be Happier

But one of the team's most intriguing findings was that people in mission-control tend to be happier than Americans in general, but that astronauts who are flying are even happier than mission-control staff.“ In spite of the pressure and dangers they face in their work, they are having a ball,” Kanas noted.

There may be several possible explanations for this finding, Kanas said. One may be that they are especially resilient since they had to be found mentally fit before being selected by NASA. Another may be that they are a special group that sees the world very positively—in fact, there is evidence to that effect. Still a third is that they have finally, after years of planning and working toward their goal, achieved it and find it fantastic. Finally, their bliss may stem from their being able to view Earth from outer space.

Indeed, Kanas and his team surveyed 39 astronauts who had been in space to learn what they had found positive there. What the astronauts rated most highly was being able to view Earth from outer space—to appreciate its beauty, to sense that Earth has no borders, and that all humans on Earth are one species. “And in some cases, when they returned, it affected their desire to improve things and get involved in helping other people,” Kanas said.

Results Reaching Psychiatrists

But are the results that Kanas and his team are obtaining helping others?“ We hope so,” Kanas replied. “We write reports for NASA, and I'm fairly sure that the psychiatrists and psychologists working at Johnson Space Center, as well as their Russian counterparts in Moscow, are reading them and learning from them. I've also had occasion to debrief astronauts.”

And their results have implications for psychiatry in general, Kanas believes. “For example, while people who are selected to be astronauts do not have family histories of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, they do react to stress, they may have transient depression or homesickness, and they may exhibit psychosomatic reactions in space. We are learning to deal with such problems remotely. It is a nice model for how to do telepsychiatry in remote areas on Earth.

“Also, just as astronauts engage in displacement when working under stressful conditions, so do small stressed groups of people on Earth. A possible solution for such displacement, whether on Earth or in space, might be to let members of a stressed group hold “bull sessions” and air their problems rather than let problems fester and complain to people outside the group.”

Their Sight Is on Mars

Meanwhile, Kanas and his colleagues are forging ahead to learn more about the psychology of space travel. They are writing a proposal to study the psychology of autonomy on the International Space Station. The reason, Kanas explained, “is that if NASA sends a manned mission to Mars in the 2030s, as is currently planned, crews will be more autonomous in their work than ever before. For instance, if astronauts were on Mars, hundreds of millions of miles away from Earth, with up to 44 minutes of delayed communication between themselves and mission control, they would really feel isolated. You couldn't send them surprise packages or supplies. If someone had a medical emergency, you couldn't evacuate them home. How would astronauts deal with such conditions? We would like to find out.” ▪