VA Struggles to Meet Follow-Up Care Recommendation

The Department of Veterans Affairs would need to find new ways of delivering care and additional millions of dollars to pay for it, if it provided all recommended suicide-prevention monitoring visits during high-risk periods following antidepressant treatment changes.

Even then, the VA wouldn't know for sure if the added effort would save lives because there is still too little information by which to judge the value of increased monitoring in decreasing suicide, wrote Marcia Valenstein, M.D., M.S., and colleagues, in the April Psychiatric Services. Valenstein is a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan School of Medicine and is affiliated with the Ann Arbor VA Medical Center.

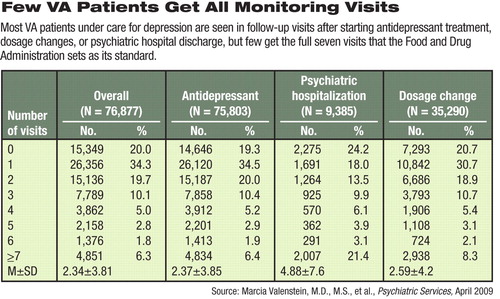

Figure. Few VA Patients Get All Monitoring Visits

Attempting to reduce suicide among newly treated patients, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2005 recommended monitoring with seven clinic visits in the 12 weeks following the start of antidepressants, dosage changes, and psychiatric hospitalizations. However, the current study of 100,000 VA patients treated for depression found that veterans completed far fewer visits than that. On average over that period, they came back for 2.4 visits after antidepressant treatment starts or dosage changes, and 4.9 visits after psychiatric hospitalization.

“The FDA's standard is hardly reached in reality, nor is the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set [HEDIS] measure of three visits,” said Valenstein in an interview. “Despite the FDA guideline, we're seeing no sign of an upward swing in the frequency of follow-up.”

Clinicians often view the FDA standards as expensive and logistically difficult to implement in practice, she said.

“It would take a lot of reorganizing and cost quite a bit more to deliver seven visits to every person with an antidepressant event in the first 12 weeks,” she said, even though treated veterans experience fewer than one of these high-risk periods a year.

The sample of 100,000 patients was randomly selected from 887,859 in the VA's National Registry for Depression. They had received either two diagnoses for depression or one diagnosis and an antidepressant prescription filled between April 1999 and September 2004.

The number of patients treated for depression nationwide has increased in recent years, but the number of patient visits related to it has decreased.

Suicide rates among these depressed veterans were also high, according to previous research by the same group. Overall, there were 114 suicides per 100,000 person-years over 60 weeks following a treatment event. Suicide rates for all VA enrollees in 2000-2001 were 43 per 100,000 person-years for men and 10 per 100,000 for women. The overall national suicide rate in 2005 was 11 per 100,000 persons, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, rates were higher in the first 12 weeks after a treatment event and varied with the nature of the treatment. Patients discharged from VA psychiatric hospitalization committed suicide at a rate of 568 per 100,000 person-years, 210 per 100,000 after new antidepressant starts, and 154 per 100,000 after dose changes. These high suicide rates suggest that something—possibly close monitoring—might help reduce them. Those at highest risk were adults aged 61 to 80 in the first 12 weeks, according to prior research by Valenstein and colleagues.

However, only 6.4 percent of all patients and 21 percent of hospitalized patients had seven visits in 12 weeks after their first treatment event.

Paying for a full set of visits is another issue. Seven office visits would cost the VA $408 to $537 a patient in the 12 weeks following an antidepressant treatment event or $313 to $341 after psychiatric hospitalization. The VA would have had to spend another $183 million to $270 million to cover visits by all the patients in the registry during each 12-week period following an antidepressant event. Costs might be lower if telephone contacts were used and would be higher if psychiatrists or skilled psychotherapists rather than other types of practitioners provided the follow-up services.

Money is not the only issue, said the researchers. “The VA would need to substantially reorganize depression services to provide monitoring consistent with the most stringent FDA recommendations.”

It may be too early in any case to mandate more follow-up visits, said Valenstein. No trials have demonstrated that seven visits—or more, or fewer—would change suicide rates.

APA practice guidelines currently state that patients who start taking antidepressant medications “should be carefully monitored to assess their response to pharmacotherapy as well as the emergence of side effects, clinical condition, and safety,” but that the frequency of such monitoring visits depends on “the severity of illness, the patient's cooperation with treatment, the availability of social supports, and the presence of comorbid general medical problems.”

The observational study doesn't address the relationship between the number of visits logged by VA patients and suicide, she said. “This is difficult to do because sicker people would be seen more often, and so more sophisticated analytic techniques are required to accurately delineate that information.”

So far, wrote the authors, “suicide prevention studies concluded that only physician education and restricting access to lethal means have reasonable evidence for efficacy in preventing suicide.”

Her research provides the impetus for further assessment of increased visit frequency on suicide risk, said Valenstein. “We need good data on the relationship between the number of visits and the occurrence of suicide to justify making changes during any high-risk periods.

This research was supported by the VA Health Services Research and Development Service and the National Institute of Mental Health.

“Service Implications of Providing Intensive Monitoring During High-Risk Periods for Suicide Among VA Patients With Depression” is posted at<http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/60/4/439>.▪