Several Factors Deter Spouses From Getting Depression Care

Depressive symptoms among spouses of soldiers preparing for deployment to Iraq are relatively high and are accompanied by increased perceived barriers to care, according to research by military psychiatrists.

Maj. Christopher Warner, M.C., a psychiatrist, and three colleagues surveyed the spouses (96 percent of whom were wives) of a brigade combat team at Fort Stewart, Ga., preparing to leave for deployment. They e-mailed the survey to a convenience sample of 872 spouses enrolled in the unit's Family Readiness Group, and 295 (34 percent) responded to questions about the stresses they faced and depressive symptoms. About 86 percent were married to an enlisted soldier, the rest to officers.

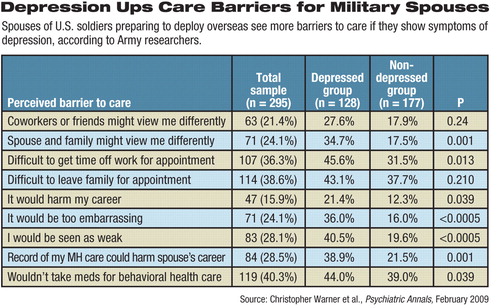

Figure. Depression Ups Care Barriers for Military Spouses

Six stressors topped the checklist on the questionnaire. At least 90 percent of the spouses said that “feeling lonely” and “the safety of my deployed spouse” concerned them most. More than half of the spouses said communications problems with the spouse, raising young children alone, and balancing work and family obligations also troubled them.

About 44 percent (128) of the spouses met Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) criteria for depression, and 24 percent (75) recorded mild depressive symptoms, said the researchers. Higher scores on the Perceived Stress Scale were associated with greater risk of meeting criteria for depression after adjustment for demographic, family, and military factors.

Perceived barriers to care were higher among respondents who met criteria for depression. Compared with nondepressed respondents, significantly more of these spouses worried about how they would be seen by others or the effects on their spouse's career if they entered care.

Concern about the spouse's career increased with age and with the number of prior deployments, wrote the researchers. “[T]his provides additional evidence that each military service must continue its programs to reduce stigma and actual career consequences for those seeking health care.”

Preparing for deployment obviously is a stressful time for the entire family, yet some results of the study also suggested areas of resiliency for those affected. For instance, having more children in the home was not a risk factor for depression, nor were repeated deployments, said the researchers.

“Deployments are like kids—the first one is the hardest,” said psychiatrist Harold Ginzburg, M.D., J.D., M.P.H., a former U.S. Navy physician. Ginzburg was the guest editor of the special February Psychiatric Annals in which Warner's article appeared.

“People gain more knowledge, learn how to handle it better, and use the social supports around them,” he said in an interview. “They either get into the groove or get out of the service, so it's a form of self-selection.”

The effects of deployment on families won't dissipate easily, even after their soldiers return home, so they will bear watching, said Ginzburg.“ It would seem prudent to prospectively study this cohort to determine the long-term social consequences of this conflict.”

An abstract of “Psychological Effects of Deployments on Military Families” is posted at<www.psychiatricannalsonline.com/view.asp?rid=37164>.▪